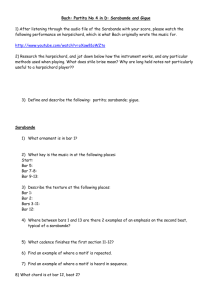

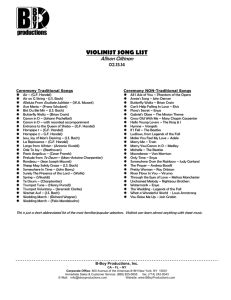

About the music Goldberg Suite

advertisement

About the music Though I strive for consistency of style and idiom within a single piece of music, I accept no obligation to keep to a fixed sound-world from one composition or improvisation to the next. It might then be said, as Samuel Barber once said of himself, that I have no style at all; but if this versatility makes it harder to recognize many of my pieces as coming from the same composer’s hand, it makes it easier to avoid monotony in a recital of my music. Even so, there are some compositional concerns that inform all of my work, be its vocabulary that of the Baroque, of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, or of jazz: clarity of overall structure, a fascination with counterpoint and rhythm, and with few exceptions a harmonic language ultimately grounded in common-practice tonality. Goldberg Suite Bach’s Goldberg Variations are his longest composition for keyboard, and by such a wide margin that it has been suggested that if Bach envisioned any kind of performance then it would be not of the entire set but of selected movements played in the manner of a suite. The Goldberg Suite is such a selection, except that more than half of the music in it is new. Still, every movement is a Goldberg variation in the sense that it closely follows the fixed chord progression and also, though less closely, adheres to Bach’s keyboard idiom. In addition to this constraint of uniformity, the new variations (with the inevitable exception of the Sarabande) also adhere to Bach’s principle of variety: none of them sounds like a specific one of Bach’s variations, nor are any two of the new ones alike. Overture (Variation 16). A natural starting point is the variation that opens the second half of Bach’s cycle, and is written in the “French Overture” style (as Bach announces by calling it “Ouverture”): a stately introduction in a dotted or double-dotted rhythm, then a faster fugato section. Such movements start many of Bach’s own dance suites. Sarabande (Variation 13/13a). In Bach’s 13th variation the right hand gently spins out a richly embellished melody in the manner of a violin solo over a steady Sarabande rhythm in the left hand. In such movements it is customary for the repeats to be ornamented, but here there is hardly room for further decoration; instead the repeats turn the melody upside down — falling where Bach’s rises, and vice versa — while keeping the left hand largely intact. Bourrées (Variation 36: canons at the 12th). Every third Goldberg variation is a exact canon: the two upper voices play the same melody separated by one or more beats, starting on the same pitch in Variation 3, one note apart in Variation 6, two in Variation 9, three in Variation 12, and so on until Variation 27. The Bourrées are exact canons a half-beat and 11 notes apart, and thus naturally fit into the pattern as Variation 36. As often happens at this point in a Baroque suite, there are two separate Bourrées, the second slower and in minor mode, followed by a reprise of the first. Gigue (Variation 2 12 ). The Gigue is the fast concluding movement of most Suites, and Bach’s gigues often feature virtuosity of both counterpoint and keyboard technique. While the name refers to the British jig, by Bach’s time gigues need not be suitable for actual jig dancing, and indeed one of Bach’s gigues is in a fast 4/2 time! My Gigue is in 5/8, with cross-rhythms suggesting 4/8, 3/8 or 2/8 divisions as well. The P.D.Q.Bach-style number “2.5” refers both to this 5/8 meter (2 12 quarters) and to an earlier piece, my “2 21 -part invention” written in a similar rhythmic and contrapuntal manner. Veritas Quodlibet (Variation 1636). The 28th and 29th Goldberg Variations sound like a grand virtuosic finale, but Bach is not done yet. Variation 30, where we might have expected a tenth canon, is instead an intricately crafted joke, weaving two German folk-songs into the Goldberg chord changes in various canons and combinations. The Veritas Quodlibet attempts to do the same thing with two tunes that many Harvard listeners will recognize. Reprise (Diagonal Variation). Bach’s Quodlibet is followed by the marking “Aria da capo”, indicating that the original theme is to be repeated at the end, for a total of 32 movements. Instead I play the first two bars of the theme, the next two bars of Bach’s first variation, the next two of the second, and so forth until reaching the last two bars of the reprise of the theme. This can succeed (with some tweaking at the boundaries) because every variation is based on the same harmonic pattern, which is automatically inherited by the ”diagonal” variation. This variation may be regarded as a radically abridged rendition of Bach’s full variation set, or at least a mnemonic for the order of its 32 movements. Ohrwurm-Walzer: Waltz on a fragment by Tárrega “Ohrwurm”, literally “ear-worm”, is a colorful German word for a tune or snippet of music we cannot get out of our head. The worm that turns this piece is a brief phrase from the middle of an intimate waltz for solo guitar by Francisco Tárrega (1852–1909). While Tárrega is otherwise little known except to classical guitarists, a quirk of fate and technology has turned these four measures into one of the most often heard tunes in the world. At first I knew this fragment only by the incongruous name “Grand Vals” that Tárrega gave his piece, so I tried to imagine a grand waltz based on the phrase; Ohrwurm-Walzer is the eventual result. Wedding Toccata My sister Galit asked me to write a piece to perform at her 2004 wedding to Daniel, based on motives formed from the letters GALIT and DANIEL according to a musical alphabet I learned many years ago from Sylvia Rabinof. The resulting toccata also incorporates, in the opening and towards the end, the names of Galit’s three daughters from her previous marriage.