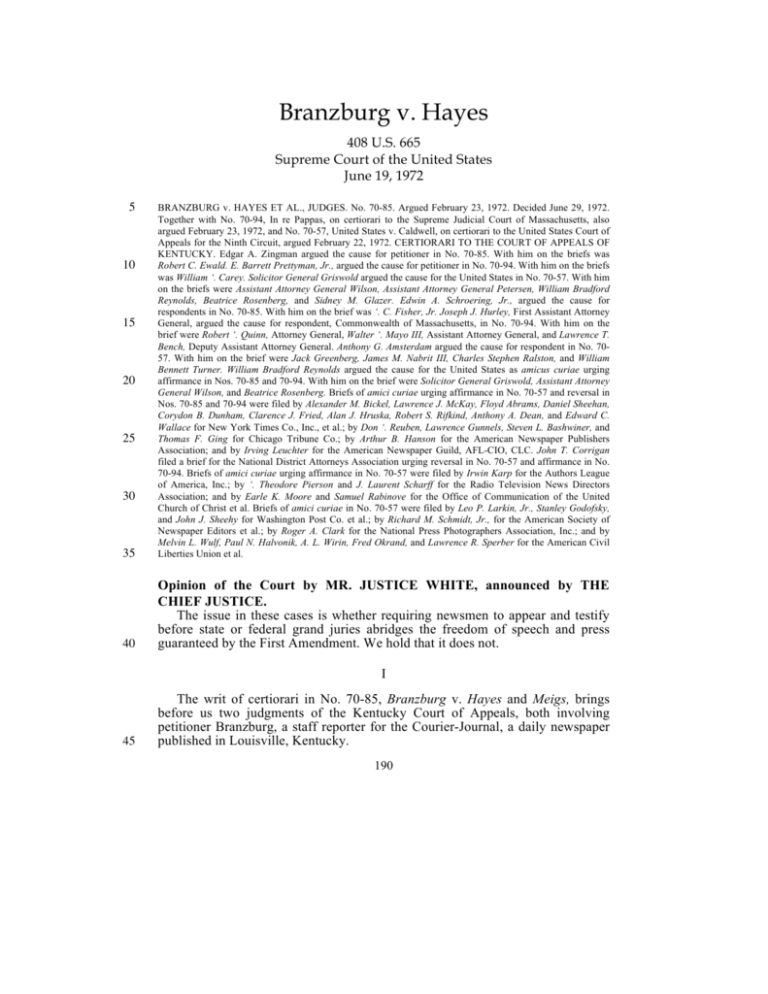

Branzburg v. Hayes

advertisement