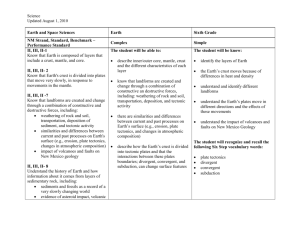

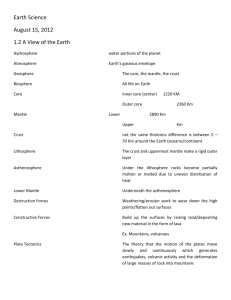

Chapter 3 – Earth Structure

advertisement

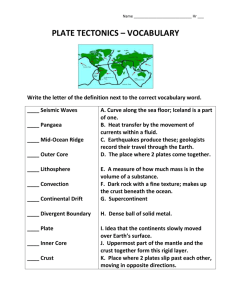

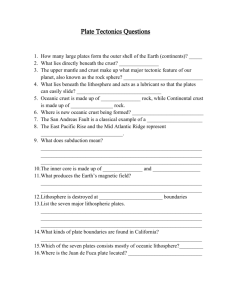

Chapter 3 – Earth Structure Waves associated with earthquakes: P waves – Primary, compressional, compressional, arrive first, pass through solid, liquid and gas, oscillate in the direction of propagation Geologic Structure of Earth - The interior of the Earth is layered. Concentric layers: crust, mantle, liquid outer core and solid inner core. Evidence (indirect) for this structure comes from studies of Earth’ Earth’s dimensions, density, rotation, gravity, magnetic field, behavior of seismic waves and meteorites. S waves – Secondary, ‘sideside-toto-side’ side’ or shear waves, arrive second, cannot pass through liquid, pass through solid, oscillate in the direction transverse to propagation Seismograph P S Mantle 1 Focus 2 0 10 P Core S 20 Minutes 30 40 50 Surface waves 4 5 Evidence that supports the idea that Earth has layers comes from the way seismic waves behave as they encounter different material inside Earth and as the material is either liquid or solid Density is a key concept for understanding the structure of Earth – differences in density lead to stratification (layers). Density measures the mass per unit volume of a substance. Density = _Mass_ Volume Density is expressed as grams per cubic centimeter. Water has a density of 1 g/cm3 Granite Rock is about 2.7 times more dense 3 6 1 Earth’ Earth’s layers – chemical composition and physical properties Summary Table 1 – Physical Properties ¾Core: Core: ~ 3500 km thick, average density 13 g/cm3, 30% of Earth’ Earth’s mass and 16% of its volume • Inner core: core: radius of 1200 km, primarily Fe & Ni @Temp of 40004000-5500° 5500°C, solid, av. den. 16 g/cm3 • Outer core: 3200°C, core: 2260 km thick, Temp of 3200° liquid (partially melted), viscous, less dense ¾Mantle: Earth’s mass & 80% of its volume, 2866 km Mantle: 70% Earth’ thick, @ Temp of 100100-3200° 3200°C, MgMg-Fe silicates, solid but can flow, average density 4.5 g/cm3 Layer Chemical Properties Continental Crust Composed primarily of granite Density = 2.7 g/cm3 Oceanic Crust Composed primarily of basalt Density = 2.9 g/cm3 Mantle Composed of silicon, oxygen, iron, and magnesium Density = 4.5 g/cm3 Core Composed primarily of iron Density = 13 g/cm3 Note: inner core may be rotating faster than mantle – can be hotter than the Sun’ Sun’s surface (more than 6, 500 deg C!!) ¾Earth’ Earth’s outer layer is the Crust: cool, rigid, thin surface layer – rocks on crust side are chemically different than rocks on mantle side – separation is called Mohorovičić 7 discontinuity Earth’s Crust: cold, brittle 10 Summary Table 2 – Composition thin layer, 0.4% of Earth’s mass and 1% of its volume ¾Continental Crust: •Primarily granitic type rock (Na, K, Al, SiO2) •40 km thick on average •Relatively light, 2.7 g/cm3 ¾Oceanic Crust •Primarily basaltic (Fe, Mg, Ca, low SiO2) •7 km thick •Relatively dense, 2.9 g/cm3 Layer Physical Properties Lithosphere Cool, rigid, outer layer Asthenosphere Hot, partially melted layer which flows slowly Mantle Denser and more slowly flowing than the asthenosphere Outer Core Dense, viscous liquid layer, extremely hot Inner Core Solid, very dense and extremely hot ¾cool, solid crust and upper (rigid) mantle “float” and move over hotter, deformable lower mantle 8 Lithosphere & Asthenosphere:: More detailed description of Earth’s layered structure according to mechanical behavior of rocks, which ranges from very rigid to deformable 1. lithosphere: rigid surface shell that includes upper mantle and crust (here is where ‘plate tectonics’ work), cool layer 2. asthenosphere: layer below lithosphere, part of the mantle, weak and deformable (ductile, deforms as plates move), partial melting of material happens here, hotter layer (100 – 200 km) (200 – 400 km) 9 11 Isostasy A term used to refer to the state of gravitational equilibrium between the lithosphere and the asthenosphere, which makes the plates (seem like) “float” at an elevation that depends on their thickness and density – areas of Earth’s crust get to this equilibrium after rising and subsiding until their masses are in balance. Less dense continental blocks “float” on the denser mantle 12 2 displaced water Buoyancy: a 10 kg object can float if it lands on a liquid (water) body large enough that the object can displace a volume of liquid that weighs 10 kg and there is still more liquid left Buoyancy: depends on the mass and density of the object and of the liquid in which object floats Icebergs: 10% of volume above water, 90% of volume below surface Earthquake epicenters Heat flow Ocean Sediments Radiometric dating of rocks of ocean and continental crust • Magnetism • • • • 13 Isostatic equilibrium: continental mountains float high above sea level because the lithosphere sinks slowly into the deformable asthenosphere until it has displaced a volume of asthenosphere equal to the mass of the mountain’s mass. Very slow process – if it goes too fast for some reason then the rock will crack (fracture) and a fault occurs, and cause earthquakes Evidence for Seafloor Spreading 16 Age of Earth was not easily determined, nor accepted as ‘that old’! The Fit between the Edges of Continents Suggested That They Might Have Drifted The fit (first noticed by Leonardo da Vinci) of all the continents around the Atlantic at a water depth of about 137 meters (450 feet), as calculated in the 1960s. This well-known graphic was a very effective kick-off to the ‘tectonic revolution’. 14 Chapter 3 – on to Plate Tectonics Movement of the Continents – Continental Drift • Continents had once been together advanced by Alfred Wegener during the 1920’ 1920’s • Ultimately rejected – Until new technology provided evidence to support his ideas. ¾Seismographs revealed a pattern of volcanoes and earthquakes. ¾Radiometric dating of rocks revealed a surprisingly young oceanic crust. ¾Echo sounders revealed the shape of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge 15 17 Synthesis of Continental Drift and Seafloor Spreading --> --> Theory of Plate Tectonics Main points of theory (Wilson, 1965): ¾Earth’s outer layer is divided into lithospheric plate ¾Earth’s plates float on the asthenosphere ¾Plate movement is powered by convection currents in the asthenosphere seafloor spreading, and the downward pull of a descending plate’s leading edge. Hess and Dietz in 1960 proposed a model to explain features of ocean floor and of continental motion powered by heat Æ mantle convection 18 3 heat transfer: conduction (contact) Age of sea floor vs. distance from ridge crest convection (motion of an agent, currents) Figure 2.13 Lithosphere A plate is the cooled surface layer of a convection current in upper mantle. Heat source tectonic plate is the cool surface, the result of a convection current rising from the (hot) upper mantle (spreading center) – as it cools it becomes denser so gravity ‘pulls’ it down (subduction 19 zone) heated water rises, cools at the surface and falls around the container’s edge 22 Age and thickness of sea floor sediment Model of Mantle Convection spreading centers – where new sea floor and oceanic lithosphere form subduction zones – where old oceanic lithosphere descends 20 23 Improved Mapping, WWII Convergent plate boundary marked by trench Asthenosphere Africa Divergent plate boundary marked by mid-ocean ridge Transform fault (spreading center) Oceanic lithosphere Subduction fueling volcanoes Asia Chapter 3 – Plate Tectonics Descending plate pulled down by gravity Philippine Trench Mantle upwelling Superplume Outer core Mariana Trench Mantle Mid-Atlantic Ridge Inner core Hot South America Cold Possible convection cells ¾Plate Tectonics – a unified model with ideas from continental drift and sea floor spreading ¾Lithosphere broken into plates ¾Plates move Rapid convection at hot spots ¾Boundaries between plates are sites of geologic activity Peru–Chile Trench Hawaii East Pacific Rise 21 24 4 Earthquake Epicenters Shallow epicenters – crustal movement (less than 100 km) As plates float on the deformable aesthenosphere, aesthenosphere, they interact among each other. The result of these interactions is the existence of 3 types of boundaries: Mid-deep epicenters subduction (greater than 100 km) • 25 Plates Æ Rigid Slabs of Rock Divergent: plates move away from each other, examples: * Divergent oceanic crust: the Mid-Atlantic Ridge * Divergent continental crust: the Rift Valley of East Africa (b) Convergent: plates move toward each other. Three possible combinations: continent-ocean, ocean-ocean, continent-continent (c) Transform: neither (a) nor (b), plates slide past one another – transform faults. * Example: San Andreas fault 28 Fracture Zones-Transform faults Seven major plates – Pacific, African, Eurasian, North American, Antarctic, South American, Australian Minor plates – Nazca, Nazca, Indian, Arabian, Philippine, Caribbean, Cocos, Cocos, Scotia, Juan de Fuca 26 29 27 30 Plate boundaries in action: (1) plates move apart, (2) plates move toward each other, (3) plates move past each other 5 Oceans are created along divergent boundaries East African Rift System Recall that seafloor spreading was an idea proposed in 1960 to explain the features of the ocean floor. It explained the development of the seafloor at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Convection currents in the mantle were proposed as the force that caused the ocean to grow and the continents to move. The breakdown of Pangea showing spreading centers and mid-ocean ridges 2 kinds of plate divergences 31 34 Island Arcs Form, Continents Collide, and Crust Recycles at Convergent Plate Boundaries Mid Atlantic Ridge South Indian Ridge Convergent Plate Boundaries - Regions where plates are pushing together can be further classified as: • Oceanic crust toward continental crust the west coast of South America. • Oceanic crust toward oceanic crust occurring in the northern Pacific. • Continental crust toward continental crust – one example is the Himalayas. 3 kinds of plate convergences 32 35 Convergent Plate Boundaries Modern divergence East African Rift System • Continent – Ocean • Ocean – Ocean • Continent – Continent 33 36 6 Convergent Plate Boundaries Ocean-Ocean Aleutian Islands, Alaska Continent – Ocean West Coast of South America 37 40 • Continent – Ocean Ocean – Ocean Caribbean Islands • Mount St. Helens 38 Island Arcs Form, Continents Collide, and Crust Recycles at Convergent Plate Boundaries The formation of an island arc along a trench as two oceanic plates converge. The volcanic islands form as masses of magma reach the seafloor. The Japanese islands were formed in this way. 9 9 9 9 Many discoveries contribute to the theory of plate tectonics but the most compelling evidence comes from The Earth’s Magnetic Field • Rocks record the direction of magnetic field (Magnetite) • Magnetic field direction changes through geologic time – polar reversals recorded in rocks * 560 °C = rock solidifies (Curie Point) * Captures magnetic signature • Particles of Magnetite align with the direction of Earth’s magnetic field at the time of rock formation Motion of the plates: plates: Mechanisms – not fully understood Rates: average 5 cm/year MidMid-Atlantic Ridge = 2.5 – 3.0 cm/yr EastEast-Pacific Rise = 8.0 – 13.0 cm/yr 41 39 42 7 axis of Earth’s rotation Chapter 3: Summary Keep in mind that the important points in this chapter are: angle about 11.5° magnetic NP-SP axis 1. ‘huge’ magnet 2. 3. 4. Magnetites occur naturally in basaltic magma and act as compass needles 5. 6. 7. 8. Internal Layers: inner core, outer core, mantle, crust (continental (continental and oceanic). P and S waves – used to study Earth’ Earth’s layered structure Lithosphere and Asthenosphere – defined according to mechanical behavior of rocks Isostasy – pressure balance between overlying crust and astheosphere deformation Continental drift – plates/continents moving about surface; deduced from definitive evidence: ridges, rise, trench system, sea sea-floor spreading, spreading centers, subduction zones Evidence of crustal motion: earthquakes epicenter, heat flow, radiometric dating, magnetism Plate Tectonics – 7-8 major plates, 3 types of plate boundaries Convergent Plate Boundaries – oceanocean-continent, oceanocean-ocean, continentcontinent-continent 43 The patterns of paleomagnetism support plate tectonic theory. The molten rocks at the spreading center take on the polarity of the planet while they are cooling. When Earth’s polarity reverses, the polarity of newly formed rock changes. (a) When scientists conducted a magnetic survey of a spreading center, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, they found bands of weaker and stronger magnetic fields frozen in the rocks. (b) The molten rocks forming at the spreading center take on the polarity of the planet when they are cooling and then move slowly in both directions from the center. When Earth’s magnetic field reverses, the polarity of new-formed rocks changes, creating symmetrical 44 bands of opposite polarity Plate Movement above Mantle Plumes and Hot Spots Provides Evidence of Plate Tectonics 46 Chapter 3: Key Concepts Some seismic waves–energy associated with earthquakes–can pass through Earth. Analysis of how these waves are changed, and the time required for their passage, has told researchers much about conditions inside Earth. Earth is composed of concentric spherical layers, with the least dense layer on the outside and the most dense as the core. The lithosphere, the outermost solid shell that includes the crust, floats on the hot, deformable asthenosphere. The mantle is the largest of the layers. Large regions of Earth’s continents are held above sea level by isostatic equilibrium, a process analogous to a ship floating in water. Plate motion is driven by slow convection (heat-generated) currents flowing in the mantle. Most of the heat that drives the plates is generated by the decay of radioactive elements within Earth. 47 Chapter 3: Key Concepts Plate tectonics theory suggests that Earth’s surface is not a static arrangement of continents and ocean, but a dynamic mosaic of jostling segments called lithospheric plates. The plates have collided, moved apart, and slipped past one another since Earth’s crust first solidified. The confirmation of plate tectonics rests on diverse scientific studies from many disciplines. Among the most convincing is the study of paleomagnetism, the orientation of Earth’s magnetic field frozen into rock as it solidifies. (See also Figure 3.33 on page 89 of textbook) Formation of a volcanic island chain as an oceanic plate moves over a stationary mantle plume and hot spot. In this example, showing the formation of the Hawai’ian Islands, Loihi is such a newly forming island. 45 Most of the large-scale features seen at Earth’s surface may be explained by the interactions of plate tectonics. Plate tectonics also explains why our ancient planet has surprisingly young seafloors, the oldest of which is only as old as the dinosaurs – that is, about 1/23 of the age of Earth. 48 8