Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World.

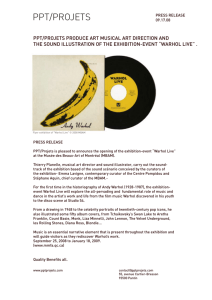

advertisement