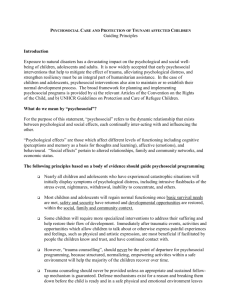

Drug and Alcohol Psychosocial Interventions

advertisement