How female Impressionist - Durham University Community

advertisement

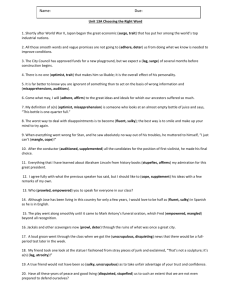

Kaleidoscope 6.2. Special Issue, Zozia Eyres, “Reclaiming Impressionism: How female Impressionist painters challenged the status quo” Reclaiming Impressionism: How female Impressionist painters challenged the status quo ZOZIA EYRES In her seminal text “The Second Sex”, Simone de Beauvoir writes that “one is not born, but rather becomes a woman.”1 She therefore makes an important distinction between sex and gender; the former being a biological difference and the latter being the “cultural meaning and form that the body acquires.”2 The subject of gender is vital in studying the history of art but is also something that has, until recently, been very much neglected. All seventy-three artists mentioned in the contents of Pierro Ventura’s book “Great Painters” are male and unless one interprets this to mean that women are simply less talented than men, this suggests that there were cultural factors prohibiting women from being successful within the art establishment.3 Men have been the painters, purchasers and consumers of art and this means that the modern spectator sees history from a male standpoint when looking at the visual arts. Therefore what will first be examined is how male artists portrayed a gendered view of the world; mainly in relation to how male Impressionists treated the subject of the female. This period is also incredibly important because it is perhaps the first time that female artists such as Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt managed to make an impact. Gender is a key theme in these artists’ work; it affected both what they could paint and how they chose to explore their subject and this is what we will examine. In 1863, Charles Baudelaire wrote his essay “The Painter of Modern Life.” In this work, one thing that Baudelaire discusses is how women are viewed by the (male) painter and this stance on the female carried on between 1870 and 1900. He writes that “woman is for the artist in general… an idol, stupid perhaps, but dazzling and bewitching… everything that adorns women that serves to show off her beauty is part of herself… no doubt woman is sometimes a light, a glance, an invitation to happiness, sometimes she is just a word.”4 Baudelaire shows us that, for male artists, women were valued solely for the aesthetic value of their bodies– they were both as important as an idol and as unimportant as a word. This contemporary view of gender affected male painters because it meant that these artists treated the subject of woman with a scopophilic eye - or ‘gaze’- which would then translate to the male viewer of the artwork. Such ideas led to paintings that portrayed man very much as the master and woman as the subject because, as Luce Ingriray has said, “More than other senses, the eye objectifies and masters. It sets at a distance and maintains a distance… The moment the look dominates, the body loses its materiality.”5 This male dominance and female passiveness within Impressionist art is evident in Renoir’s La Loge (fig. 1) which depicts two people in a theatre box. The figure of the woman is placed in the foreground which suggests that she is on display and the detailed front of her dress, which Renoir meticulously paints in contrast to the less careful brushstrokes of the rest of the painting, draws attention to her chest. Boime has commented that the female figure looks “as if she were there to be gazed at and is self-conscious of the fact… the fact that her companion scans the upper tiers for a substitute emphasizes masculine superiority and freedom at the expense of the female who is locked in as an object on display.”6 This act of looking by the man in the painting is something that gives the figure power and we know that there were significant 1 de Beauvior(1986: 267) Butler (1986: 35) 3 Ventura (1987: 1) 4 Baudelaire, (1964:14) 5 Irigray, (1978:50) 6 Boime (1994: 35) 2 89 Kaleidoscope 6.2. Special Issue, Zozia Eyres, “Reclaiming Impressionism: How female Impressionist painters challenged the status quo” attempts for women to be excluded from this as the opera glasses they were given had plain glass in them instead of the lenses that the opera glasses of male theatre-goers had. Therefore, Renoir’s painting shows the effects of gender on Impressionist art because it reinforces the social construct that the male role is to look and the female role is to be seen. Degas too was preoccupied with the act of looking in relation to women. “More than three-quarters of the total number of works of art produced by Degas are representations of women”7 and the viewpoints he uses to depict this subject are significant. For instance, in Woman Drying Herself (fig. 2), we see him adopting a ‘keyhole’ perspective which gives the viewer the position of a voyeur. The nude who is drying herself faces away from the onlooker, suggesting that she does not know that we are there, that we are intruding. The image was made using the tactile medium of pastel which would be rubbed by the artist to produce the desired effect - suggesting the touching of the subject. In contrast to this lower viewpoint, in Nude in a Tub (fig.3), we look down on a female in the bath but this still produces the effect of being a secret watcher. Kendall comments that “situated above, but often quite close to, his subjects, the artist could observe without participating, viewing his subjects like a concealed observer or ‘fly on the wall.’”8 This can create a feeling of unease within the modern viewer as it suggests that Degas is taking advantage of his subjects, indeed we know that the artist used to run his hands over his models before he started painting. The fact that these “plunging perspectives, bird’s-eye views and intrusive lines of vision were reserved by the artist for those subjects which were (again literally and metaphorically) beneath him”9 is troubling as it means that Degas used these exploitative viewpoints with models who were of a lower class and likely desperate for work. It is therefore evident that gender greatly affected much of male Impressionist art because of its frequent focus on the female subject and how it approaches this. The painters’ male ‘gaze’ represents models as objects to take sexual pleasure from, even extending to a voyeuristic approach in which the artist and viewer seem complicit in the illicit viewing of women. So how did this view of gender affect female artists during this period? Griselda Pollock has written that “there is a historical asymmetry – a difference socially, economically, subjectively between being a woman and being a man in Paris in the late nineteenth century. This difference – the product of the social structuration of sexual difference and not any imaginary biological distinction – determined both what and how men and woman painted.”10 This difference in how women painted is particularly important because the restrictions placed on women in this period determined what they could paint. Firstly, the male establishment ensured that female artists had very little access to artistic training as women were not allowed to enrol in the main place of learning – the Academy in Paris – until 1897. This meant that most women did not have formal artistic training which would greatly affect their ability to paint certain subjects, for instance they were not permitted to attend life drawing classes which would have taught them about how to accurately portray the human body. In fact, the only reason that the more successful female artists from the period were able to learn their trade and enter the Impressionists’ circle was through their connections to the men within it. Morisot was taught by her brother-in-law Manet, Bracquemond was married to an important artist of the day, Felix Bracquemond, and Cassatt had to rely on Degas after she struggled to finish the artistic education that she had started in the more liberal America. However, even after these women were able to overcome this obstacle, their choice of subject was greatly limited by society’s views on gender. It is significant “how little of typical impressionist iconography actually appears in the works made by artists who are women. They do not represent the territory which their colleagues who were men so freely occupied and made use of in their works, for instance bars, cafes, backstage”11 and this is because they simply could not frequent these places. Women were not allowed to leave the house unchaperoned and even then could not visit many areas of Paris; the artist Marie Bashkirsteff’s diary shows how much this affected the ability of women to express themselves. She writes, “what I long for is the freedom of going out alone, of coming and going… that’s what I long for; and that’s the freedom without which one cannot become a real artist. Do you imagine that I get much good from what I see, chaperoned as I am?”12 Being supervised inhibited creativity which means that much of female Impressionist art is set in the ‘domestic sphere’ where women could paint alone. However, this does not mean that these artists refrained from showing their frustration through their work as for the first time female artists started 7 Kendall (1989: 6) Kendall (1989:9) 9 Kendall (1989: 9) 10 Pollock (1992: 55) 11 Pollock (1992:56) 12 Bashkirsteff (1985: 21) 8 90 Kaleidoscope 6.2. Special Issue, Zozia Eyres, “Reclaiming Impressionism: How female Impressionist painters challenged the status quo” challenging traditional views on gender by portraying a female view of the world and showing how stifling their containment was. The composition of Morisot’s paintings shows the cut-off between the female ‘domestic sphere’ and male ‘public sphere’ very effectively through a use of concrete physical boundaries that divide the picture space of her works. For instance, On the Balcony (fig. 4) represents a mother and daughter standing on a balcony and the line of the balustrade cuts diagonally through the painting. The two figures are cramped into the narrow pictorial space of their home while the wide expanse of Paris lies in the distance. Morisot shows us the city how a woman would see it, as a far-away space reserved for men and the detail of the child’s face pressed up to the railings suggests that she may as well be leaning against prison bars. This motif of incarceration can also be seen in Cassatt’s painting Five O’Clock Tea (fig. 5) in which the striped wallpaper behind the figures illustrates how the women are entrapped in their environment. The table and chair surround the figures, confining them into a constricted area of the picture and even the tea set impinges on the woman who is drinking. The forced gestures of the figures, such as the woman on the right lifting her little finger while sipping her tea, suggest the farce of the ceremony of having five-‘o’-clock tea and the boredom in the faces of the women suggests a passive resistance to their situation. The artist shows this opposition more explicitly in her painting Woman in Black at the Opera (fig.6.) which takes a very different approach to the same subject of the Renoir painting that was explored earlier. The woman in Cassatt’s painting is shown to be looking through her opera glasses while a man on the other side of the opera circle looks at her through his. Boime argues that this is to show that “the doltish male seeks drama not from the stage but in the private exchange being played out in the public space of entertainment. The woman is unaware of his gaze… she engages with the creative event on stage – the mark of her superiority and refinement.”13 However, we may want to take a different approach to the painting because the woman in Cassatt’s painting is not looking downwards towards the stage but is instead looking out across the theatre circle. This suggests that Cassatt’s woman is controversially exhibiting a female ‘gaze’ and that by including the male figure who is looking through his glasses, the artist is acknowledging the male ‘gaze’ and is contesting it. Cassatt’s woman is certainly not on display as an erotic object, her black clothes cover most of her body and we therefore see a figure that has seized the power to look instead of just being looked at. Cassatt is acknowledging her society’s view of gender and reversing it through her artwork. In conclusion, it is evident that gender greatly impacted upon male and female artists in France between 1870 and 1900. The male Impressionists could wander around Paris with freedom and portrayed their frequent subject of woman as simply an object to be looked at and coveted. In contrast to this, female Impressionists were greatly restricted by the social conventions of the day; it was difficult for them to gain formal training and their movements were isolated to certain areas of Paris in the company of a chaperone. Artists such as Cassatt and Morisot responded to this by creating paintings that focused on these feelings of suffocation in the hope of educating the male viewer. These female artists used their work to challenge the much-accepted gendered view of the world by putting forward a female picture of life and by undermining the status quo. They therefore paved the way for women to follow as they consistently tried to show that, in the words of Cassatt, “women should be someone not something.”14 The practice of art history itself has been greatly affected by gender as these female Impressionists had, until recently, been largely ignored by critics. Perhaps now, as views on gender progress, we will see these revolutionary female artists being rediscovered and appreciated. Bibliography Bashkirsteff, M. (1985), Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff, trans. Mathilde Blind, M., London: Virago. Baudelaire, C. (1964), The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, Oxford: Phaidon. Boime, A.,“Maria Deraismes and Eva Gonzalès: A Feminist Critique of A Feminist Critique of ‘Une Loge aux Théâtre des Italiens’”, Woman’s Art Journal, 1994, No. 15/2, pp31-37. Butler, J., ‘Sex and Gender in Simone de Beauvoir's Second Sex’, Yale French Studies, 1986, No. 72, pp35-49. Cassatt, M. (1966), quoted in Sweet, R. Miss Mary Cassatt, impressionist of Pennsylvania, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. De Beauvoir, S., (1976) The Second Sex, New York: Alfred A Knopf. Irigray, L., (1978) interview in Hans, F. and Lapouge, G. (eds) Les Femmes, la pornographie et l’erotisme. 13 14 Boime (1994:35) Cassatt as quoted in Sweet (1966: 136) 91 Kaleidoscope 6.2. Special Issue, Zozia Eyres, “Reclaiming Impressionism: How female Impressionist painters challenged the status quo” Kendall, R., (1989) ‘Degas’ Discriminating Gaze’, in Kendall, R. (eds), Degas: Images of Women, London: Tate Gallery Publications. Pollock, G., (1992) ‘Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity’, in Frascina, F. & Harris, J. (eds), Art in Modern Culture, London: Phaidon. Ventura, P., (1987) Great Painters, London: Kingfisher Books Ltd. Index of Images Figure 1, La Loge, Renoir, 1874. http://www.renoirgallery.com/paintings/large/renoir-the-theater-box.jpg [accessed 15/03/14] Figure 2, Woman Drying Herself, Degas, c.1890-95. http://www.nationalgalleries.org/collection/artists-az/D/3051/artist_name/Edgar%20Degas/record_id/4998 [accessed 15/03/14] 92 Kaleidoscope 6.2. Special Issue, Zozia Eyres, “Reclaiming Impressionism: How female Impressionist painters challenged the status quo” Figure 3, Nude in a Tub, Degas, 1884. http://uploads0.wikipaintings.org/images/edgar-degas/nude-in-atub-1884.jpg [accessed 15/03/14] Figure 4, On the Balcony, Morisot, 1872. http://uploads6.wikipaintings.org/images/berthe-morisot/womanand-child-on-the-balcony.jpg [accessed 16/03/14] Figure 5, Five-‘o’-clock Tea, Cassatt, 1880. http://www.artchive.com/artchive/c/cassatt/cassatt_le_the.jpg [accessed 16/03/14] 93 Kaleidoscope 6.2. Special Issue, Zozia Eyres, “Reclaiming Impressionism: How female Impressionist painters challenged the status quo” Figure 6, Woman in Black at the Opera, Cassatt, 1891. http://arthistoryoftheday.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/cassatt_opera1.jpg [accessed 16/03/14] Zozia Eyres College of St Hild and St Bede Durham University Zozia Eyres is a second-year Combined Honours Arts student reading English Literature, History of Art and Ancient History at the College of St Hild and St Bede. This paper was prepared as part of the ‘Introduction to Modern Art’ module under the guidance of Dr Anthony Parton. 94