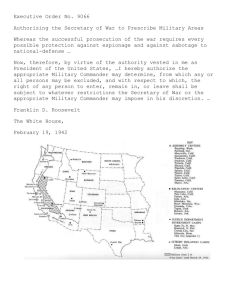

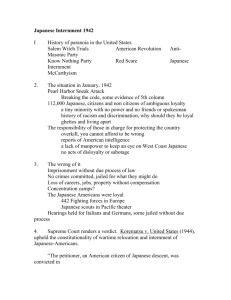

When National Security Trumps Individual Rights

advertisement