The Transom Review: Rick Moody

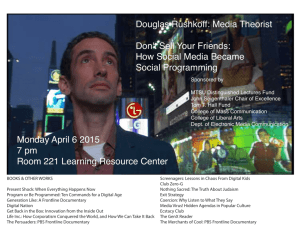

advertisement