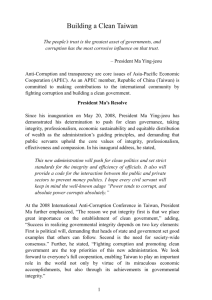

human nature and morality in the anticorruption discourse

advertisement