Towards a Symphony of Instruments

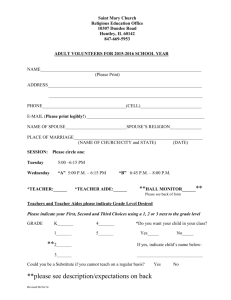

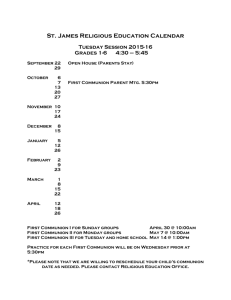

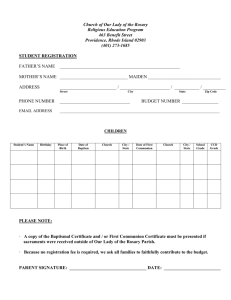

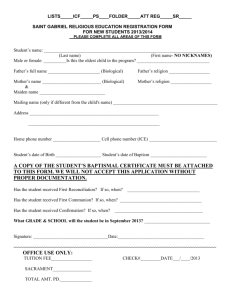

advertisement