Dendrochronologia 32 (2014) 1–6

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Dendrochronologia

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dendro

Original article

Comparing methods to analyse anatomical features of tree rings with

and without intra-annual density fluctuations (IADFs)

Veronica De Micco a,∗ , Giovanna Battipaglia b,c , Paolo Cherubini d , Giovanna Aronne a

a

Dip. Agraria, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, via Università, 100, I-80055 Portici, NA, Italy

Dip. Scienze e Tecnologie Ambientali, Biologiche e Farmaceutiche, Seconda Università di Napoli, via Vivaldi 43, 81100 Caserta, Italy

c

Centre for Bio-Archeology and Ecology, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (PALECO EPHE), Institut de Botanique, University of Montpellier 2, F-34090

Montpellier, France

d

WSL Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research, CH-8903 Birmensdorf, Switzerland

b

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 30 July 2012

Accepted 1 June 2013

Keywords:

Dendroecology

Intra-annual density fluctuations (IADFs)

False rings

Mediterranean tree-rings

Quantitative wood anatomy

Vessel size

a b s t r a c t

Different methods to analyse variations in vessel size in tree rings with and without intra-annual density fluctuations (IADFs) in Erica arborea L. are presented. These methods are based on the in continuum

collection of vessel size data within the ring using digital images. In the analysis of rings from the early(EW) to late-wood (LW), the following vessel parameters were determined: (a) progressive number, (b)

lumen area, and (c) lumen centre of gravity (i.e. distance between lumen centre and EW beginning). To

make rings of different width or number of vessels comparable, progressive number and centre of gravity

variables were standardised. Different graphical representations and data interpolation techniques were

compared. Our results indicate that the most consistent procedure to measure the position and width of

IADFs along tree rings should include the following steps: (a) plotting vessel lumen area in relation to

standardised progressive number, (b) interpolation of vessel area series using simple moving average, (c)

superimposition of curves from series of tree rings with and without IADFs, and (d) the establishment of

the points where the two series intercept. Our results show that, in diffuse-porous woods, vessel position

can be represented by a simpler automatically detected parameter, thus simplifying the procedure for

data collection and analysis. The proposed graphical representation also facilitates the establishment of

links between IADFs and ecological processes.

© 2013 Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Wood is the long-term memory of the history of a tree, because

tree rings record the signs of plant growth reactions behind biotic

and environmental influence. Both gradual variability in environmental factors and extreme events can be recognised in specific

traits of tree rings at anatomical and chemical levels. As summarised by Rossi and Deslauriers (2007), “wood is not just the simple

addition of unaltered elements like bricks on a pre-existing wall”.

Indeed, xylem formation is the result of cambial cell division and

processes of cell growth and differentiation. These phenomena are

regulated by several intrinsic factors (e.g. gene expression, hormonal signals and interaction between cell wall components), as

well as environmental factors (e.g. temperature and precipitation)

(Grozdits and Ifju, 1984; Wardrop, 1965; Deslauriers and Morin,

2005; De Micco et al., 2010; Lupi et al., 2010).

∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +39 081 2532026/2539443; fax: +39 081 7755114.

E-mail address: demicco@unina.it (V. De Micco).

1125-7865/$ – see front matter © 2013 Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2013.06.001

Dendrochronology has emerged as a discipline studying tree

growth during long-time scales, to link tree-ring features and

climatic information in order to estimate retrospectively past

environmental dynamics. In the last decades, dendrochronology

has been supported more and more by other disciplines mainly

focusing on the study of cambial activity, quantification of wood

anatomical features and analysis of stable isotopes (De Micco et al.,

2007; Battipaglia et al., 2009; Rossi et al., 2012). Such a multidisciplinary approach helps extracting ecophysiological information

from tree rings (Fonti and García-González, 2004; Battipaglia et al.,

2007, 2010; Fonti et al., 2010; Moreno-Gutiérrez et al., 2012).

In dendroecology, the traditional weakness of using a minimum

time resolution of 1 year has been solved by introducing analytical approaches at shorter time scales (Rossi and Deslauriers, 2007).

Intra-annual analyses of tree rings allow a finer understanding of

plant growth responses to environmental variability. Moreover,

they help the interpretation of Intra-Annual-Density-Fluctuations

(IADFs), also known as false- or double-rings, which are generally

detected as abrupt changes in the wood density of tree rings. Initially investigated to solve problems of cross-dating due to false

rings consequent to frost events (Glock, 1951), IADFs have been

2

V. De Micco et al. / Dendrochronologia 32 (2014) 1–6

more and more used to relate specific wood regions along a tree

ring to precise climatic anomalies, thus allowing reconstructing

detailed environmental information at a seasonal level. Such an

approach enhances that, apart the three spatial dimensions, wood

is characterised by a fourth dimension, namely time (Glock and

Reeds, 1940; Wimmer, 2002; Edmondson, 2010). The use of IADFs

as intra-annual pointers of climatic abrupt variations is particularly

interesting in shrub species of the Mediterranean area, where the

high frequency of IADFs hampers tree-ring dating (Cherubini et al.,

2003). Indeed, IADFs proved to be a valuable tool helping the interpretation of the main climatic factors driving wood formation in

Arbutus unedo L. and Pinus halepensis (Battipaglia et al., 2010; de

Luis et al., 2011).

As recently reported by Eckstein and Schweingruber (2009),

the quantification of specific wood anatomical features in treering series is expanding in tree-ring research, because the response

of trees to environmental changes is stored not only in tree-ring

width, wood density and isotope composition, but also in many

other anatomical features. However, different anatomical traits

are often highly correlated and can be considered interchangeable

indicators of changing environmental conditions during tree-ring

formation (Wimmer, 2002). It goes without saying that there might

be a natural tendency to consider anatomical traits easy to measure

and free from the operator subjectivity as much as possible. Definitely, the amount of time and labour needed for the collection

of wood structural data has discouraged thorough studies based

on large sampling (Gartner et al., 2002). The introduction of new

techniques for automatic assessment of wood anatomical features

has been a drive versus the development of quantitative wood

anatomy as a discipline strictly related to dendrochronology (Fonti

et al., 2010). However, the presence of tools for rapid assessment of

anatomical features can still not completely solve the problems of

subjectivity if correct standardisation of measurement and internal

controls are not established (Gartner et al., 2002; De Micco et al.,

2012).

In this paper, we present a comparison between different methods used to analyse vessel size variation in tree rings with and

without IADFs. Such methods are based on the collection of vessel

size data in continuum, along tree rings, in standardised transects

on digital images. Our aim was to verify whether, in the analysis of

vessel size variation along tree rings, data of vessel size need to be

coupled with data about the exact position of each vessel relative to

the ring boundary as done in Battipaglia et al. (2010). We hypothesise that, in a diffuse-porous wood, vessel position can be replaced

by a more easily detectable parameter: the progressive number

at which each vessel is automatically detected when scanning the

image for the analysis from the beginning of tree-ring (earlywood)

towards its ending (latewood). The investigation was focused on

Erica arborea L., a species common in the Mediterranean maquis,

whose wood has a tendency to form frequent IADFs.

data are from the Portoferraio meteorological station located at

10 km from the sampling site (42◦ 49 N, 10◦ 20 E, 25 m a.s.l.).

Tree-ring dating, selection of tree rings with and without IADFs in

microsections

Twenty plants (2–3 m height, 4–8 cm diameter), not multistemmed, were sampled. Three disks from the base of each shrub

were cut and air dried. In all samples, tree-ring width was measured

using a LINTAB linear table and a micrometer with a resolution

of 0.01 mm. Then samples were visually crossdated (Stokes and

Smiley, 1968) and the program COFECHA (Holmes, 1983) was run

to validate the crossdating and to find potential errors.

Subsamples from each disc were cross-sectioned with a sliding microtome. Sections (15 m thick) were stained with safranin

and astra blue, dehydrated through an ethanol series, immersed in

xylene and mounted on slides with Canada balsam (Schweingruber,

1978; Gärtner et al., 2001). The micro-sections were studied under

a transmitted light microscope (Olympus BH-2, Germany) and

compared to the correspondent cross-dated disks to identify IADFs.

These were classified according to their position along tree-ring

width following Battipaglia et al. (2010). 78 tree rings were selected

for subsequent anatomical measurements. More specifically, 39

tree rings were without IADFs (i.e., normal rings with a gradual

transition from early-to latewood), while 39 showed middle-IADFs

(i.e., rings characterised by a layer of latewood-like xylem elements

in the middle of earlywood). For the analysis of anatomical parameters, the two groups of rings with and without IADFs were randomly

separated into two series of three replicates each (13 rings per

replicate).

Quantitative wood anatomy and data elaboration

Plant material

Microsections of the selected rings were analysed under a transmitted light microscope (BX60, Olympus). Photo-micrographs of

them, including the whole tree-ring width, were taken with a digital camera (CAMEDIA C4040, Olympus). The images were analysed

with AnalySIS 3.2 (Olympus) to quantify anatomical features. In

each microphotograph, a transect, 300–400 m wide, throughout

the ring, was selected (Fig. 1a and b). Care was taken in order to

make the beginning of each transect correspond to the beginning

of earlywood (EW). Similarly, the end of each transect had to correspond to the ending of latewood (LW). In each transect, anatomical

parameters were automatically measured in all vessel elements

encountered moving from the left (beginning of EW) to the right

(ending of LW), following the in continuum method described by De

Micco et al. (2012). More specifically, per each encountered vessel,

the following parameters were measured: (a) lumen area, (b) the

centre of gravity of lumen defined as the Y-distance between the

lumen centre and the left border of the transect (beginning of EW).

During the measurement, the progressive number of each vessel

was recorded while scanning the transect from left to right.

Measured parameters were used to build dispersion graphs with

Y and X as coordinates of each vessel. Y corresponded to vessel

lumen area and Xi was defined according to four methods as follows.

Stem disks were sampled from E. arborea L. plants growing on

Isola d’Elba, an island in the Tyrrhenian sea (Italy). The main vegetation type of the island is maquis, and the climate is Mediterranean,

with hot and dry summer, followed by mild and wet autumn and

winter (Daget, 1977; Nahal, 1981). During the period 1970–2007,

the average summer and winter temperatures were 23.4 and

9.4 ◦ C, respectively, while precipitation was mainly concentrated

in autumn and winter, with an annual average of 375 mm. Climatic

(1) X1 = Absolute progressive number: the progressive number of

vessel detection while scanning the transect from left to right.

(2) X2 = Absolute centre of gravity: the centre of gravity of vessel

lumen (i.e. vessel distance from the beginning of the transect).

(3) X3 = Standardised progressive number: the progressive number

of vessel detection (while scanning the transect from left to

right), standardised dividing by the total number of vessels

encountered along the transect and multiplying by 100. In other

Materials and methods

V. De Micco et al. / Dendrochronologia 32 (2014) 1–6

3

to the distance between the beginning of the transect and the

last crossing between the two curves, either SMA or PC (Fig. 1c,

short arrow). According to these two principles, we calculated IADF

width as difference between Xend and Xbeg . IADF width was thus

measured following four procedures:

(a) Xend and Xbeg values taken from PC lines in graphs built with

Standardised progressive number (3p);

(b) Xend and Xbeg values taken from SMA lines in graphs built with

Standardised progressive number (3 m);

(c) Xend and Xbeg values taken from PC lines in graphs built with

Standardised centre of gravity (4p);

(d) Xend and Xbeg values taken from SMA lines in graphs built with

Standardised centre of gravity (4 m).

Data of IADF beginning and ending (i.e. Xbeg and Xend ) obtained

through the four procedures were compared by means of ANOVA

using SPSS statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Multiple comparison tests were performed with LSD, Bonferroni

and Student–Newman–Keuls coefficients using P < 0.05 as the level

of probability.

Results

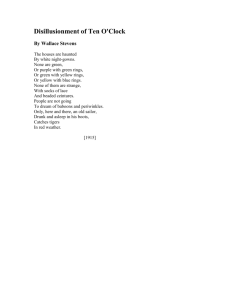

Fig. 1. Microphotographs of tree rings without (a) and with (b) middle-IADF, showing the selection of a transect for vessel size detection. Bar = 100 m. Example of a

dispersion graph (c) with polynomial curves interpolating vessel-size data from tree

rings with middle-IADFs (black line) and without IADFs (grey line). Arrows point to

the beginning and ending of IADF.

words, the total number of vessels in each transect was always

considered equal to 100. In a diffuse-porous wood, X3 can be

considered as a parameter indicating the distance from the

beginning of the ring, expressed as a percentage of ring width.

(4) X4 = Standardised centre of gravity: the centre of gravity of vessel

lumen standardised with the whole ring width being considered equal to 100%. This standardisation was obtained by

dividing the Absolute centre of gravity by the total ring width and

multiplying by 100. In other words, X4 corresponds to the distance from the beginning of the ring, expressed as a percentage

of ring width.

The patterns of vessel size variability along ring width, obtained

through the four types of dispersion graphs, were visually compared in rings with and without IADFs.

Definition of the IADF region and statistical analyses

In the standardised data series (methods n. 3 and n. 4), simple

moving average (SMA, 40-points) and interpolation equations (PC,

fourth-order polynomial curve) were calculated. Per each couple

of replicates (13 rings with middle-IADF + 13 rings without IADFs),

dispersion graphs of data from tree rings with middle-IADF were

superimposed to those of rings without IADFs (Fig. 1c).

The beginning of IADF was assumed as the X-value (Xbeg ) corresponding to the distance between the beginning of the transect

and the first crossing between the two curves (point where the two

curves diverge), either with SMA or PC (Fig. 1c, long arrow). The

ending of IADF was assumed as the X-value (Xend ) corresponding

Tree rings without IADFs of E. arborea were characterised by

diffuse porous wood, mainly composed of solitary vessels. Rings

showed a gradual transition from earlywood, with large vessels,

to latewood with narrower vessels (Fig. 1a). Rings with IADFs

appeared as double rings where a sudden decrease in vessel lumen

size occurs in the middle of earlywood, forming a band of latewoodlike cells (Fig. 1b).

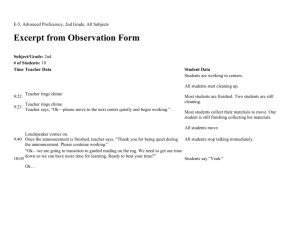

The graphs in Fig. 2 report the trends of vessel size variation

along the tree ring following the four proposed methods in both

rings with and without IADFs. The trend of gradually decreasing

vessel size typical of tree rings without IADFs clearly emerged only

when a standardisation of the position of each vessel along the ring

was considered (Fig. 2c and d; methodologies n. 3 and n. 4, based

on Standardised progressive number and Standardised centre of gravity respectively). When data standardisation was not performed

(Fig. 2a and b; methods n. 1 and n. 2 based on Absolute progressive

number and Absolute centre of gravity respectively), graphs failed

to illustrate reliable trends of gradual decrease of vessel size from

earlywood to latewood in rings without IADFs (Fig. 2a and b). In

rings with IADFs, methods n. 1 and n. 2 failed to reveal reliable

trends of vessel size variation as well (Fig. 2a and b). Only graphs

built with X-axis corresponding to Standardised progressive number or Standardised centre of gravity allowed to evidence the typical

trend of vessel size variation of rings with middle-IADFs (Fig. 2c

and d). This trend is characterised by the occurrence of an abruptly

steep decrease of vessel lumen area in the middle of earlywood, followed by an increase of vessel size which reaches, moving towards

latewood, values higher than those generally measured in rings

without IADFs at the corresponding ring width. Fig. 2 confirms

that to obtain reliable information on the patterns of vessel size

variation in tree rings with and without IADFs, data need to be standardised according to ring width: methods n. 3 and n. 4 have to be

followed. As a consequence, subsequent elaborations were done on

methods based on Standardised progressive number or Standardised

centre of gravity. Fig. 3 reports the dispersion graphs obtained by

plotting the whole set of data [vessel size coupled with either Standardised progressive number (method n. 3, Fig. 3a–c) or Standardised

centre of gravity (method n. 4, Fig. 3d–f)] of a replicate of rings without IADFs (Fig. 3a and d) and with middle-IADFs (Fig. 3b and e).

In the four dispersion graphs, PC and SMA are reported. Although

4

V. De Micco et al. / Dendrochronologia 32 (2014) 1–6

different trends of vessel size variation between tree rings with and

without IADFs were evident when analysing the dispersion graphs

of the whole set of raw data (Fig. 3a, b, d and e), polynomial curves

were characterised by low correlation coefficients (0.20 < r2 < 0.41),

with minimum values occurring in rings with IADFs. The graphs in

Fig. 3c and f were built by superimposing PC and SMA curves of

tree rings with IADFs to those without IADFs according to methods n. 3 (Fig. 3c) and n. 4 (Fig. 3f). The analysis of graphs in Fig. 3c

and f indicated that both methods n. 3 and n. 4 allow the detection

of IADF in the same region of tree rings. These graphs were used

to calculate the Xbeg (beginning) and Xend (ending) values according to the two types of data interpolations. More specifically, the

Xbeg and Xend values derived always from graphs based on a standardised vessel position [i.e. either progressive number (Fig. 3c) or

centre of gravity (Fig. 3f)], but interpolated either with polynomial

curve or simple moving average. Statistical comparison between

data obtained following the four different methods showed that

there are no significant differences between the percentage of ring

width at which the IADFs begin (Xbeg ) and end (Xend ) in the four

cases (Fig. 4). In other words, the position and size (width) of IADFs

is always the same notwithstanding the method followed to calculate its beginning and ending.

Discussion

Fig. 2. Variation in vessel lumen area (VLA) along ring width in tree rings with

IADFs (black lines) and without IADFs (grey lines). X-data are relative to the four

methods: (a) absolute progressive number (APN); (b) absolute centre of gravity (ACG);

(c) standardised progressive number (SPN); (d) standardised centre of gravity (SCG).

Simple moving average is reported.

Dendrochronology has been increasingly interacting with other

disciplines, also introducing analytical approaches at time scales

shorter than one year (Rossi and Deslauriers, 2007). The analysis

of intra-annual variations of anatomical and isotopic data in tree

rings helps improving the extraction of ecophysiological information with seasonal time scale especially when IADFs are frequent

(Battipaglia et al., 2010). However, the correct identification of

IADFs is required as well as a correct standardisation of measurement procedures is needed to reduce subjectivity in data collection.

In our paper, we propose a new approach for the study of IADFs in

tree rings to reach a more objective classification and analysis of

IADFs features. The proposed method might follow the traditional

dendrochronological analysis which allows IADFs identification

through cross-dating techniques (Cherubini et al., 2003). We aimed

to verify whether, in the analysis of intra-annual chronologies of

vessel size in a diffuse-porous wood, it is possible to avoid coupling

data of vessel lumen area with data about the exact position of each

vessel along the ring. In order to do this, we visualised in dispersion graphs data of vessel lumen area coupled with four sets of data

(absolute progressive number, absolute centre of gravity, standardised progressive number and standardised centre of gravity) referred

to the position of each vessel along the tree ring. When absolute

values were considered, the evidenced trends of vessel size variation along the tree ring from earlywood to latewood were not

reliable either in rings with and without IADFs, partly due to the

lack of synchronization among tree rings characterised by different widths or number of vessel elements. Only graphs built with

X-axis corresponding to Standardised progressive number or Standardised centre of gravity allowed to evidence the typical trend of

vessel size decrease from earlywood to latewood in rings without

IADFs, and the typical vessel size fluctuation in the middle of earlywood in rings with middle-IADFs. The latter trend is characterised

by the occurrence of an abruptly steep decrease of vessel lumen

area in the middle of earlywood, followed by an increase of vessel size which reaches, moving towards latewood, values higher

than those generally measured in rings without IADFs at the corresponding ring width. This phenomenon is in agreement with vessel

lumen area variation evidenced in tree rings with IADFs in A. unedo

L. (De Micco et al., 2012). The analysis of data in E. arborea allowed

V. De Micco et al. / Dendrochronologia 32 (2014) 1–6

5

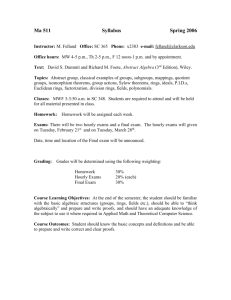

Fig. 3. Dispersion graphs obtained by plotting the whole set of vessel lumen area (VLA) and standardised data of a replicate of rings with IADFs (b and e) and without IADFs

(a and d). Polynomial curves and Simple moving average are shown for data measured with method n. 3 (based on standardised progressive number – a, b and c) and method

n. 4 (based on standardised centre of gravity – d, e and f).

us to confirm that to obtain reliable information on the patterns

of vessel size variation in tree rings with and without IADFs, data

need to be objectively standardised according to ring width to avoid

incorrect identification of IADFs and misleading interpretations of

anatomical variation at IADF level.

Once established the need to standardise the position of each

measured vessel, we verified that both interpolation with simple

moving average (SMA) and polynomial curves (PC) allowed to identify reliable trends of vessel size variation. Moreover, the position

and size (width) of IADFs was always the same notwithstanding

the interpolation method followed to calculate their beginning

and ending. However, the use of SMA should be preferred because

this parameter is more robust than polynomial curves (PC), especially when correlation coefficients are low, given that PC patterns

can change depending on their order. Our finding of the occurrence of lower correlation coefficients in tree rings with IADFs is in

agreement with the higher variability between rings under variable

environmental conditions (Battipaglia et al., 2010).

Therefore, the easiest and fastest procedure to detect and measure the position and width of IADFs along tree rings would

be: (a) the construction of dispersion graphs based on X-values

corresponding to the standardised progressive number, (b) the interpolation of the data series with simple moving average (SMA), (c)

Fig. 4. Comparison among the four methods to calculate the percentage of ring

width at which the IADFs begin (Xbeg ) and end (Xend ). 3p, polynomial curve (PC)

in graphs showing standardised progressive number; 3 m, simple moving average

(SMA) in graphs showing standardised progressive number; 4p, PC in graphs showing

Standardised centre of gravity; 4 m, SMA in graphs showing standardised centre of

gravity. Mean values and standard errors are shown. Different letter correspond to

significantly different values (P < 0.05).

6

V. De Micco et al. / Dendrochronologia 32 (2014) 1–6

the superimposition of curves belonging from the data series of tree

rings with and without IADFs, and (d) the analysis of points where

the two curves cross each other.

The use of standardised values allowed overcoming the problems related to the comparison between rings characterised by

different width. Moreover, our data demonstrate that in a diffuseporous wood, as that of E. arborea, the Standardised progressive

number can be used instead of the Standardised centre of gravity,

thus disregarding the information about exact vessel position. The

Standardised progressive number, being an easy parameter to detect,

helps quickening the procedure of data acquisition and treatment. This is in agreement with the general tendency to simplify

methodologies and to use anatomical characters easy to measure

(Wimmer, 2002). Besides, it encounters the general need to follow

automatic procedures to quickly collect anatomical data from large

number of samples and avoid subjectivity (Gartner et al., 2002; De

Micco et al., 2006).

In conclusion, the comparison between the different methods

reported in this paper allowed to indicate the first easy and quick

procedure of digital image analysis and data treatment to detect

the size and position of IADFs along tree rings.

Moreover, the graphs proposed, deriving from the superimposition of tendency curves of tree rings with and without IADFs,

can be useful also for ecological interpretations. Indeed, the position of the ring where the IADF begins (Xbeg ) might be related to

the period of the season when the stress priming the fluctuation

occurs. The width of IADFs might be related to the duration of conditions triggering their formation, while the Y-difference between

the two curves might give an idea of the magnitude of the stress

conditions. In this specific case study, the size of IADFs could be

related to the duration and intensity of a sudden drought during

earlywood formation in E. arborea. Such a phenomenon would be

in agreement with what found in other species such as A. unedo

and P. pinaster where the sudden decrease of conduit size in earlywood was accompanied by increased ı13 C values and interpreted

as stomata closure due to an unexpected period of drought (De

Micco et al., 2007; Battipaglia et al., 2010). Indeed, the proposed

procedure to analyse vessel size variation in tree rings might be

useful for ecological interpretations especially in Mediterranean

tree rings which have a tendency to form frequent IADFs. Given

that this procedure provides reliable understanding of vessel size

variation along tree rings with and without IADFs in diffuse porous

species, it will likely work also on softwoods whose conduits are

even more ordered.

Considering that environmental conditions, and consequently

also tree-ring features, can encounter variations from year to

year (De Micco and Aronne, 2009; de Luis et al., 2011), the proposed procedure has been devised to make general trends emerge,

supporting further studies combining integrated dendroecological

approaches.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank L. Nardella (Parco Nazionale dell’Arcipelago

Toscano) and D. Giove (Comunità Montana dell’Arcipelago

Toscano) for assistance in the field. We also acknowledge W.

Schoch, H. Gärtner and M. Nötzli for their support during the laboratory phase of this project.

References

Battipaglia, G., Cherubini, P., Saurer, M., Siegwolf, R.T.W., Strumia, S., Cotrufo, M.F.,

2007. Volcanic explosive eruptions of the Vesuvio decrease tree-ring growth but

not photosynthetic rates in the surrounding forests. Global Change Biology 13,

1122–1137.

Battipaglia, G., Saurer, M., Cherubini, P., Siegwolf, R.T.W., Cotrufo, M.F., 2009. Tree

rings indicate different drought resistance of a native (Abies alba Mill.) and a non

native (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) species co-occurring at a dry site in Southern Italy.

Forest Ecology and Management 257, 820–828.

Battipaglia, G., De Micco, V., Brand, W.A., Linke, P., Aronne, G., Saurer, M., Cherubini,

P., 2010. Variations of vessel diameter and ı13 C in false rings of Arbutus unedo

L. reflect different environmental conditions. New Phytologist 188, 1099–1112.

Cherubini, P., Gartner, B.L., Tognetti, R., Bräker, O.U., Schoch, W., Innes, J.L., 2003.

Identification, measurement and interpretation of tree rings in woody species

from Mediterranean climates. Biological Reviews 78, 119–148.

Daget, P., 1977. Le bioclimat méditerranéen: caractères généraux, mode de caractérisation. Vegetatio 34, 1–20.

de Luis, M., Novak, K., Raventós, J., Gričar, J., Prislan, P., Čufar, K., 2011. Climate factors

promoting intra-annual density fluctuations in Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis)

from semiarid sites. Dendrochronologia 29, 163–169.

De Micco, V., Aronne, G., 2009. Seasonal dimorphism in wood anatomy of the

Mediterranean Cistus incanus L. subsp. incanus. Trees – Structure and Function

23, 981–989.

De Micco, V., Toraldo, G., Aronne, G., 2006. Method to classify xylem elements using

cross sections of one-year-old branches in Mediterranean woody species. Trees

– Structure and Function 20, 474–482.

De Micco, V., Saurer, M., Aronne, G., Tognetti, R., Cherubini, P., 2007. Variations of

wood anatomy and ı13 C within tree rings of coastal Pinus pinaster ait. showing

intra-annual density fluctuations. IAWA Journal 28, 61–74.

De Micco, V., Ruel, K., Joseleau, J.-P., Aronne, G., 2010. Building and degradation

of secondary cell walls: are there common patterns of lamellar assembly of

cellulose microfibrils and cell wall delamination? Planta 232, 621–627.

De Micco, V., Battipaglia, G., Brand, W.A., Linke, P., Saurer, M., Aronne, G., Cherubini,

P., 2012. Discrete versus continuous analysis of anatomical and ı13 C variability in

tree rings with intra-annual density fluctuations. Trees – Structure and Function

26, 513–524.

Deslauriers, A., Morin, H., 2005. Intra-annual tracheid production in balsam fir stems

and the effect of meteorological variables. Trees – Structure and Function 19,

402–408.

Eckstein, D., Schweingruber, F., 2009. Dendrochronologia – a mirror for 25 years

of tree-ring research and a sensor for promising topics. Dendrochronologia 27,

7–13.

Edmondson, J.R., 2010. The meteorological significance of false rings in eastern red

cedar (Juniperus virginiana L.) from the Southern Great Plains. Tree Ring Research

66, 19–33.

Fonti, P., García-González, I., 2004. Suitability of chestnut earlywood vessel

chronologies for ecological studies. New Phytologist 163, 67–86.

Fonti, P., von Arx, G., García-González, I., Eilmann, B., Sass-Klaassen, U., Gärtner, H.,

Eckstein, D., 2010. Studying global change through investigation of the plastic

responses of xylem anatomy in tree rings. New Phytologist 185, 42–53.

Gärtner, H., Schweingruber, F.H., Dikau, R., 2001. Determination of erosion rates

by analyzing structural changes in the growth pattern of exposed roots. Dendrochronologia 19, 81–91.

Gartner, B.L., Aloni, R., Funada, R., Lichtfuss-Gautier, A.N., Roig, F.A., 2002. Clues

for dendrochronology from studies of wood structure and function. Dendrochronologia 20, 53–61.

Glock, W.S., Reeds Sr., E.L., 1940. Multiple growth layers in the annual increments

of certain trees at Lubbock, Texas. Science 91, 98–99.

Glock, W.S., 1951. Cambial frost injuries and multiple growth layers at Lubbock,

Texas. Ecology 32, 28–36.

Grozdits, G.A., Ifju, G., 1984. Differentiation of tracheids in developing secondary

xylem of Tsuga canadiensis L. Carr. Changes in morphology and cell-wall structure. Wood and Fiber Science 16, 20–36.

Holmes, R.L., 1983. Computer-assisted quality control in tree-ring dating and measurement. Tree-Ring Bulletin 43, 68–78.

Lupi, C., Hubert, M., Deslauriers, A., Rossi, S., 2010. Xylem phenology and wood

production: resolving the chicken-or-egg dilemma. Plant Cell and Environment

33, 1721–1730.

Moreno-Gutiérrez, C., Battipaglia, G., Cherubini, P., Saurer, M., Nicolás, E., Contreras,

S., Querejeta, J.I., 2012. Stand structure modulates the long-term vulnerability

of Pinus halepensis to climatic drought in a semiarid Mediterranean ecosystem.

Plant, Cell and Environment 35, 1026–1039.

Nahal, I., 1981. The Mediterranean climate from a biological viewpoint. In: di Castri,

F., Goodall, D.W., Specht, R.L. (Eds.), Ecosystems of the World 11, MediterraneanType Shrublands. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co., Amsterdam, pp. 63–86.

Rossi, S., Deslauriers, A., 2007. Intra-annual time scales in tree rings. Dendrochronologia 25, 75–77.

Rossi, S., Morin, H., Deslauriers, A., 2012. Causes and correlations in cambium

phenology: towards an integrated framework of xylogenesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 2117–2126.

Schweingruber, F.H., 1978. Mikroskopische holzanatomie. Eidgenössische Anstalt

für das forstliche Versuchswesen. Birmensdorf, Switzerland.

Stokes, M.A., Smiley, T.L., 1968. An Introduction to Tree-Ring Dating. University of

Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Wardrop, A.B., 1965. Cellular differentiation in xylem. In: Côté, W.A. (Ed.), Cellular Ultrastructure of Woody Plants. SyracuseUniversity Press, Syracuse, NY, pp.

61–97.

Wimmer, R., 2002. Wood anatomical features in tree-rings as indicators of environmental change. Dendrochronologia 20, 21–36.