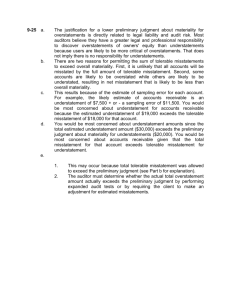

Audit Evidence - CCH Testing Center

advertisement