Recommendations for a renaissance of country parks

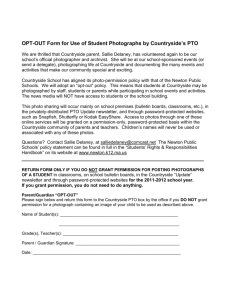

advertisement