the evolution of online marketplaces

advertisement

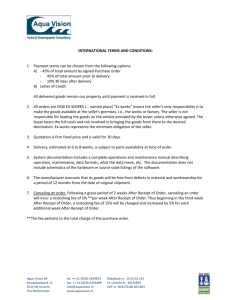

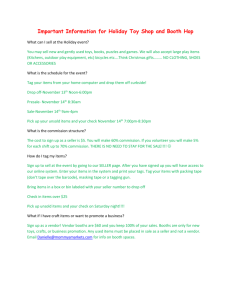

International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 247-257 (2013) 247 THE EVOLUTION OF ONLINE MARKETPLACES: A ROADMAP TO SUCCESS Nitin Walia Dauch College of Business and Economics Ashland University Ashland, Ohio, USA ABSTRACT Online marketplaces have emerged as one of the most prominent markets on the Internet. In this paper, we examine the evolution of the salient website elements and strategies as success factors in the online marketplace. The conceptual framework for this examination is based on the marketing mix theory, allowing us to formulate a success model for sellers operating in this market. The conceptual model is empirically tested by the random collection of nearly 2,500 data observations from the UK eBay Motors division for two time periods: 2006 and 2012. The results bring to light how the online marketplace has evolved and provide sellers with a roadmap for formulating their success strategies as a function of market maturity. This study is the one of first to examine the evolution of the online marketplace over a period of six years and contrasts the success factors as the market matures. Keywords: Online Marketplace, UK, eBay Motors, Market Evolution, Selling Strategies, Website Design 1 1. INTRODUCTION Online marketplaces have been widely studied, with an emphasis on the role of trust, psychological contract violation, feedback mechanisms, emotions, fraud, consumer behavior, consumer surplus, mobile shopping, segmentation of online consumers, reserve price, supply chain, sellers’ perspective, price premiums, website quality, and B2B transactions [2, 6, 7, 9, 14, 15, 17, 20, 27, 33, 37, 38, 43, 48, 50]. While the existing research has addressed multiple facets of the online marketplace, we further extend the literature by examining the evolution of online marketplaces over a period of six years. This work expands on following perspectives of the evolution of the online marketplace: (1) identification of potential website elements and strategies as success factors in the online marketplace and (2) more importantly, how these success factors evolve over time as the market mature. Hence, the research questions addressed in this study are: How do website elements and strategies evolve over time, especially as contributing factors to success in online marketplaces? To answer the research question, we conducted a longitudinal study of online marketplaces for a six-year time period from 2006 to 2012. The focus of this work is on eBay’s UK Motors division's auction * Corresponding author: nwalia@ashland.edu listings as an exemplar of online marketplaces. Data were collected during the summers of 2006 and 2012 for nearly 2,500 auctions for these two time periods. A comparative analysis between the two data-sets allows us to have a unique historical perspective of the evolution of the online marketplace while keeping possible intervening factors (such as technology advances, social changes, and global events) constant for the most part. For the theoretical foundation of this work, we rely on the marketing mix theory as well as on the relevant theories utilized in arguing for specific links in the model conceptualization. This work tests the theoretical model in the context of the UK online marketplace. UK is a global leader in electronic commerce, with the highest online spending per capita in the world. The results of this study, which look at the evolution of an online marketplace from a young to a relatively more mature market, could provide retailers with a roadmap and insight as they enter into emerging online marketplaces around the globe. 2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND RESEARCH MODEL In an online marketplace, the heterogeneity of resources available to sellers leads to variability in 248 International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 11, No. 4 (2013) market success. The heterogeneity of market-based resources could best be investigated by using the marketing mix theory. The origin of this model could be attributed to Neil Bordon, who in 1953 articulated 12 controllable factors for a successful market operation placement [46]. McCarthy [28] simplified the factors into four Ps: product, promotion, price, and placement, which have become widely popular in marketing education and practice [12]. Multiple studies have proposed inclusion of people as a distinctive element of the marketing mix [10, 20]. Hakansson and Waluszewski [18] argue that the Ps in a market mix are heterogeneous resources that should be developed and fostered dynamically in order to meet customer needs. The marketing mix theory provides us with a powerful framework for identifying and categorizing website contents that could be considered critical factors for succeeding in the online marketplace. The promotion mix (P1) reflects the ways a product is brought to the potential customer's attention. It also has its own characteristics, such as methods and frequency of promotion. The placement mix (P2) refers to how and when the product is made accessible to the customer. The price mix (P3) reflects the secondary instrument of exchange (where product is primary), which has its own characteristics, such as method and deadline of payment, discounting, and bundling prices. The people mix (P4) involves the nature of relationships established with the customer. The decisions in this mix relate to trust and the emotional aspects involving customer relationship management. The product mix (P5) identifies the instrument of exchange and includes product characteristics. The conceptual model uses these five categories as the guiding structure to identify the salient website elements that influence success in the online marketplace. The model is presented in Figure 1. Figure 1: The Online Marketplace Success Model 2.1 Measures of Success as Dependent Variables Traditionally, the success of a seller is measured by its profit and market share [32], both of which are dependent on the completion of the trade. In a few auction studies, sale above the market fair value is used as a measure of success [4, 42]. However, in many cases, including motor vehicles, the market fair value depends on the geographical location of the market. Furthermore, for a participant who needs cash right away, the utility of a quick sale may be the most important attribute, more important than selling above a given market price. In other words, participants have internal price references and the sale reflects the fact that the sale price has surpassed this internal reference. Hence, a more concrete measure of success in the online marketplace is completing the sale of the product. This measure is robust in that it reflects the satisfaction of both parties in the voluntary trade. Hence, this research considers completion of sale as a measure of success. 2.2 Web Design (P1: Promotion) Due to the virtual nature of the online marketplace, web design plays an important part in both informing the online marketplace customers about the product and providing cues about the nature and abilities of the seller. Websites constitute store fronts for the online marketplace participants. The navigation of the site resembles walking in a store and examining a product. Hence, the design of the site plays an important function [35]. Furthermore, retailers draw on signaling as a means to demonstrate their ability and intentions. Due to the inherent asymmetry of information in an online environment, consumers employ observable signals, such as web design and information, to form opinions about unobservable features, such as product quality and security and privacy [28]. Information can be presented using multiple media, pictures, audio, graphics, and animation to create a positive image of a product and brand [13]. Kwon et al. [25] observed a differentiated relationship between website design and consumers' intention to bid. On the other hand, Melnik and Alm [31] argued that images of homogeneous products do not offer additional information, whereas pictures and images of non-homogeneous products, such as coins, could increase the willingness to bid. Ottaway et al. [34] suggested that pictures invoke stronger beliefs in consumers than textual claims. Thus, sellers will be more successful in sales with a higher richness of their website. H1. A higher level of website richness is positively associated with sale. 2.3 Timing Strategy (P2: Placement) In the online marketplace, placement and availability are related to timing strategies, which include the weekend/weekday auction ending and length of the auction (bidding interval). The ending day is a placement strategy for the seller since the majority of buyers wait until the end of the bidding interval to place their bids. There is inadequate Nitin Walia: The Evolution of Online Marketplaces: A Roadmap to Success research on the effect of the ending day on success of selling in the online marketplace. According to the Pew Internet & American Life Project [39], nearly a quarter of people go online from places other than home. Furthermore, 41% of individuals access the Internet at work [52]. There is more opportunity in the weekday to access the web from work-related places. While the weekends may be occupied with home, family, and social life, the accessibility of the Internet at the workplace makes it easy to place bids or monitor the bidding process during the course of the working day. Hence, we postulate that the ending day of the bidding interval is a salient seller timing strategy, and ending the bidding interval over the weekday may produce a more successful outcome. Hence, H2a. Ending the bid on a weekday is positively associated with sale. Bidding interval or auction length (3, 5, 7, 10, 21 days) is another strategy that sellers can use in the online marketplace. Pinker et al. [40] argued that a longer bidding interval increases the number of bids since it allows more potential buyers to bid. However, a lengthy bidding interval increases the waiting time and is costlier for buyers since the item will not be available during the bidding interval. Furthermore, the majority of bidding takes place toward the end of the bidding interval [44, 47]. Bajari and Hortacsu [5] reported that 50% of bids are placed during the last 10% of the bidding interval time period, and the winning bid comes even later. Thus, the majority of bidding takes place toward the end of an auction [44]. Hence, a long bidding interval is not conducive to increasing the sale. H2b. A lengthier bidding interval is negatively associated with sale. 2.4 Pricing Strategy (P3: Price) Pricing is one of the key seller strategies in the online marketplace. Buyers are looking for the lowest possible price, and sellers want to sell at the highest possible price through their participation in the bidding process. The bidding process allows the price offered from both buyer and seller to converge, with each side relying on their internal reference price (see, for example, [9] for a review of internal reference price). Internal reference price, also sometimes referred to as fair price, acceptable price range, average price, and the last price paid, is normally a price at which the transaction would become acceptable for either buyer or seller. It has been observed that a low price lowers a buyer’s internal reference and is perceived by the buyer as a bargain [9, 23]. Studies have shown that a low starting price attracts more interest from potential buyers and further leads to “auction fever” behavior [19, 24] whereby the bidders get caught up in the competitive nature of auction and continue bidding 249 above their valuations. Thus, a relatively low starting price positively influences sale and the final price received [5, 42] by the seller. In this study, we employ "Starting Bid/Last Bid (%)" (SB/LB) as the manifestation of the seller’s pricing strategy. It is computed as the starting minimum bid set by seller as the percentage of last bid (or sale price) received on that auction. A large SB/LB indicates that the seller has set the starting price too close to the seller's internal reserve price, thus setting the starting bid at a relatively high price, which leads to a lower chance of sale. Hence, we posit H3. Higher Starting Bid/Last Bid (%) is negatively associated with sale. 2.5 Seller (P4: People)2 Trust is one of the most crucial elements in an online transaction [14, 37, 47]. In the online marketplace, we identify two source of trust: (1) the seller's reputation profile based on the eBay feedback mechanism and (2) the age of the seller, i.e., time registered on eBay. These sources induce trust in potential customers that a seller will complete the transaction as promised [45]. In the online marketplace, feedback is a public evaluation of a seller and establishes the seller's reputation within the community. Ba and Pavlou [4] considered eBay’s feedback forum as a reputation system whereby buyers evaluate sellers based on their experience with a seller. Feedback mechanism is a key element of online trust and is widely used in online commerce. Pavlou and Dimoka [36] showed that buyers’ text comments have a strong influence in sellers’ trust building. H4a. The higher level of seller reputation is positively associated with sale. Sellers that have been in operation for a long time assure potential buyers that they will not disappear after the transaction is over. The sellers in the online marketplace are individuals and entities that could exit the market once a transaction is over. This lack of perceived permanence could contribute to the reluctance of buyers to conduct a transaction with a potential seller. Thus, the age of seller (i.e., time registered on eBay) plays an important part in countering this perception; sellers who have been present in the online marketplace for a longer period of time could enhance buyers' trust. H4b. Seller’s age is positively associated with sale. Case (1) : Car A Starting Price/Bid = $2000, Last or Winning Bid = $8000, SB/LB = 25% Case (2) : Car B Starting Price/Bid = $500, Last or Winning Bid = $1000, SB/LB = 50% As the examples above show, SB/LB is a superior measure of the seller's pricing strategy compared to utilizing starting price alone. 250 International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 11, No. 4 (2013) Seller type (business or non-business) could play an important part in the online marketplace. Business Sellers include dealers, top-rated sellers, power sellers, or any other seller registered as "business" with eBay. Examples, . Business sellers might have an existing brand name and, thus, might not need to rely on online feedback mechanism to establish their reputation [8]. A business seller by its mere presence is a strong signal of the seller's legitimacy and ability to deliver on a promised transaction [49]. H4c. Business Seller as ‘seller type’ is positively associated with sale. 2.6 Product Characteristics (P5: Product) (Control Variables) Product is considered “the basic source involved in the exchange process” [18] that includes not only the salient aspects of the product (or service) in the marketplace but also additional services that come with the product, such as warranties and post-sale services. In the context of cars, the salient product characteristics include condition (used or new) and warranty. Product characteristics are controlled for this study. 2.7 Number of Bids (Control Variable) A high number of bids indicates an explicit intention to buy and, hence, could be considered as a pre-cursor of sale [16]. The public nature of the online marketplace allows potential buyers to see existing bids, which may impact their intentions, in other words, “herd behavior bias”. The relationship between bids and sale has been well established in literature [5, 16]. Thus, number of bids is a control variable. Variables Dependent Variable Sale Promotion (Website Richness) Pictures Placement (Timing Strategies) Weekday ending (Mon-Thur) Bidding interval Price (Pricing Strategy) Starting Bid (£) Last Bid(£) Starting Bid/Last Bid (%) People (Seller Trust) Feedback rating (seller reputation) Seller age Seller type Number of Bids Product characteristics Care age Engine size 3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Data were collected from eBay Motors UK. We chose eBay Motors UK since it has multiple types of participants, the products and prices are heterogeneous, and sellers use a variety of presentation styles and tools to promote their products. For the period-I, data were collected from April 2006 to June 2006, and for period-II, from May 2012 to June 2012. To collect data randomly and efficiently, a "spider" was written in Visual Basic. The spider proceeded as follows. It first gathered the unique ID of auctions about to end within 10 days. Unique IDs were collected on different days of the week and month and during different times of the day. After the closing time of the auction, the spider collected the websites’ HTML documents for each completed auction of the corresponding unique ID, with or without successful sale. The HTML document for each auction was then processed through another VB program (“Cleaner”) to condense the information about each auction into a single row of data in a spreadsheet. The program was re-written for 2012 data collection because of changes in eBay website display format. After the elimination of BuyNow cases and corrupted listings, the usable website data set contained 1,255 observations for the 2006 time period and 1,140 observations for the 2012 time period. Henceforth in this work, the term UK-I is used to denote the 2006 time period and UK-II to denote the 2012 time period for the comparisons. Variable descriptions and their measurements are reported in Table 1. Appendix A reports the descriptive statistics for the data. Table 1: Variable definitions Items Type* Product was sold or not B Number of product and non-product pictures C Whether the listing ended on a weekday Length of auction in days (3, 5, 7, 10, 21) B D Starting bid on the listing Last or winning bid Computed (SB/LB) C C The feedback score is the sum of ratings from unique users Number of months registered on eBay Business or non-business seller Number of bids received on a single listing C C B C Age of car (in years) Type of engine (in cc) C C *B=Binary, C=Continuous, D = Discrete values 251 Nitin Walia: The Evolution of Online Marketplaces: A Roadmap to Success 3.1 Comparative Analysis of the UK-I and UK-II Market To compare the differences, a multiple group analysis in Mplus was conducted for comparing differences in coefficients of the corresponding paths of the two models. A multiple group analysis is a structural equation modeling that allows the comparison of structural model differences across groups (in this study, the UK-I and UK-II time periods) [41, 10]. When examining differences across two groups, researchers have suggested comparing the model’s explained variance (r-square) and the associated path-coefficients [1]. A comparison of results (Table 2) suggests that differences exist across the two groups. In terms of the structural model, a comparison of the path coefficient suggests weekday ending, bidding interval, price, reputation, seller type, and control variables had different influences on the sale outcome across the two groups. The comparison of estimated models in the UK-I and UK-II markets indicates structural changes in the online marketplace as it matured. R2 values for the dependent variable (sale) in Model U.K-I was 0.25 (p<0.001), and in Model UK-II was.37, with p<0.001. Compared to the UK-I model, the UK-II structural model predicted 12% more variation in sale: ▲R2 Relative to UK-I =.12. Table 2: Group analysis of the model Sale UK-I (N=1255) UK-II (N=1140) Promotion(Website Richness) Number of pictures .09*** .08** Placement (Timing Strategies) Weekday ending Bidding interval .06* .03 .01 -.07* Price (Pricing Strategy) SL/LB -.09* -.32*** People (Seller Trust) Seller reputation Seller age Seller type .06** -.03 .05* .01 .03 .01 Number of Bids (control variable) .30*** .32*** Product characteristics Car age (control variable) Engine size (control variable) .12*** -.11*** .07* .03 .25*** .37*** Variables R2 In H1, it was hypothesized that website media richness has a positive association with sale. The website richness had a significant impact on sale for both markets (β =0.09, p<0.001 and β =0.08, p<0.01). Therefore, we may conclude that as the online marketplace matures, website richness continues to impact the chance of sale. In H2 (a), it was hypothesized that ending the auction on a weekday has a positive influence on sale. We have strong support for the positive influence of weekday ending on sale for the UK-I market (β =0.06, p<0.05). We found no evidence of such influence in the case of the UK-II market. The result raises the possibility that as the market matures, weekday ending may not play a strategic role in closing a sale. As to the second timing strategy, we hypothesized that bidding interval (length of auction) has a negative influence on sale (H2 (b)). The negative influence of bidding interval is observable in case of the UK-II market (β =-0.07, p<0.05). In H3, it was hypothesized that the pricing strategy in the form of a high SB/LB has a negative impact on sale. The hypothesis was supported in both the UK-I and UK-II market (β =-0.09, p<0.05 and β =-0.32, p<0.001. Thus, H3 was strongly supported. The path coefficients and significance level further indicated that this relationship was more negative in case of the more mature market -- UK-II. We hypothesized that providing seller trust elements (reputation and age) on the website increases the chances of sale (H4a and H4b). Seller reputation had significant influence on sale in the UK-I market (β =0.06, p<0.01), indicating the reliance of the customers on these cues, whereas this cue did not have any influence on sale in the UK-II market. Seller age had no significant impact on sale in either market. We also hypothesized that seller type is positively 252 International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 11, No. 4 (2013) associated with sale (H4c). Seller type had significant impact on sale for the UK-I market (β =0.05, p<0.01), indicating that business sellers are more successful, but there was no such impact in the UK-II market. 4. DISCUSSION The results of our analysis have uncovered a complex and evolving structure for eBay as a prominent online marketplace. The results of descriptive analysis and structural equation modeling indicate that online marketplace sellers deploy distinctive approaches in their web design elements and market strategies, and the impact of these strategies on sale varies as the market matures. We compared website contents and business strategies of sellers in the UK market for two periods: 2006 and 2012. The overall results provide support for the market mix model, indicating that the factors play an important role in the website design and strategies of eBay online marketplace sellers and influence their success in both the younger and mature market. 4.1 The Relationship between Media Richness and Sale The higher utilization media richness in the UK-II indicates that as the market matures, its participants provide richer website contents. The comparison of estimated models for sellers in the UK-I market and the UK-II market indicates that the impact of media richness is equally important in a younger and mature market and to gain a competitive advantage, sellers must continue provide media richness on their sites. Thus, the results are in conformance with previous literature related to website design [13, 34, 28, 50]. 4.2 The Relationship between Placement and Sale Ending the auction on a weekday as a timing strategy works only in case of a younger market but not in a mature market. The results show that as the market matures, the customers prefer shorter bidding intervals. The result from both timing strategies raises the possibility that the customers in a mature market are much more sophisticated and familiar with the online purchase process and consider longer bidding intervals costlier and wasteful. Furthermore, the results also show that as the market matures, the customers are equally comfortable with participating in online marketplace on either weekday or weekend, thus negating the impact of weekend/weekday as a strategy to influence sale. 4.3 The Relationship between Pricing and Sale The SB/LB was an important strategy for sellers. Sellers should be careful in setting relatively high starting prices, as this lowers the chance of a successful sale. The results indicate that as the market matures, the negative impact of relatively high SB/LB is even more pertinent on sale. The results show that in a mature market setting, a high starting price leads to a lower likelihood of sale. These results are different from a study conducted by Hou [19]. Interestingly the data collection for Hou [19] was done during the year 2006, classified as time period –I in this this study (year 2006). Thus, the results could be attributed as the traits of a younger market. 4.4 The Relationship between People and Sale Naturally, the average sellers’ market age and number of ratings received increases as the market matures. The comparison of estimated models for sellers in the UK-I market and the UK-II market indicate that seller reputation is positively associated with sale in the case of the younger market but not in case of the more mature market. It seems that as the online market matures and its participants increase in number, the online seller's reputation loses its significance as trust cues for enhancing the seller’s success. One reason for this phenomenon could be that in a more mature market, buyers have developed trust in the structure of the online marketplace (eBay, in this case) and placed less emphasis on the individual ratings of the sellers. This result is in conformance with the literature on online trust [37]. Another reason for this phenomenon could be that the value placed on seller’s expertise (which impacts trust in seller) is much higher in a thin market [14] compared to a mature market which has a high rate of participation by business sellers. As the participation rate of business sellers rises, there might be a reinforcement process between a seller’s online and offline reputations. Such a phenomenon has been observed in the case of established banks entering the online banking market [26]. The low percentage of business sellers in our random sample of the UK-I market indicates that the entrance of business sellers takes place at a later stage of the online marketplace evolution, when its maturity and number of participants attract business participation. Furthermore, the higher percentage of sale combined with the low number of average bids during the UK-II market shows that the conversion rate of bids to sale occurs at a higher rate at a later stage of the market maturity. 4.5 Managerial Implications One important insight from this study is that it provides a roadmap to sellers to gain a competitive advantage in online marketplace. Depending on the maturity level of online marketplace, business managers could focus on the critical success factors in online marketplaces. Sellers operating in emerging market should focus on media richness, weekday ending, setting low starting prices and seller Nitin Walia: The Evolution of Online Marketplaces: A Roadmap to Success reputation, while sellers operating in relatively mature online marketplaces should focus on media richness, shorter bidding intervals and should be careful about setting high starting prices, as this lowers the chance of a successful sale. This study not only provides a comprehensive understanding of the role of five Ps: product, promotion, price, placement, and people, it enables sellers to compartmentalize the impact of each Ps as the function of marketplace maturity. In sum, our results show that as the market matures the diversity of sellers (non-business and business) in the marketplace increases. This diversity is in conjunction with the maturity of the market structure reducing the reliance of customers on only online trust mechanisms. While in a young market, sellers may be too focused on getting large number of bids as a precursor to sale, but as the market matures, the focus moves from attracting customer (number of bids) to converting bids to sale. Furthermore, in the more mature market, customers’ expectations of a seller's website richness and contents increase. 5. CONCLUSION This study examined the evolution of salient website elements and success strategies in the online marketplace. It is predicted that the economic and social impact of the online marketplace will continue to grow. We used UK eBay as the prominent example of the online marketplace. We provided a comparative analysis of a younger and a more mature online marketplace: UK-I (year: 2006) and UK-II (year: 2012). To test our model, we randomly collected data for the transactions from the motor division of eBay in the UK during the summers of 2006 and 2012. The comparison between the two markets provides an insight into how the online marketplace evolves over time. The comparison of descriptive statistics in the two markets revealed differences in sellers’ salient web elements and strategies for participants in the two markets and provided insights into the evolution of the online marketplace over time. The estimations of the conceptual model for sellers in the UK-I and UK-II markets showed how website contents, pricing, and timing strategies impact the success of participants and the change of the market structure over time. Business sellers are late entrants in the online market; as the market matures, sellers are expected to be more sophisticated in their website design and to rely less on the market-trust cues to increase the likelihood of sale. This study has limitations that could serve as areas for further extensions. Our work could be repeated for other types of products and services. Furthermore, our results are based on data obtained from eBay as the prominent example of the online marketplace. Our work could be repeated for other 253 prominent online marketplaces, such as markets created by Amazon.com and Yahoo.com. REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Ahuja, M. K. and Thatcher, J. B., 2005, “Moving beyond intentions and toward the theory of trying: Effects of work environment and gender on post-adoption information technology use,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 427-459. Angst, C, M., Agarwal, R. and Kuruzovich, J., 2008, “Bid or buy? Individual shopping traits as predictors of strategic exit in on-line auctions,” International Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 59-84. AnnualReports.com, 2012, Available at http://www.annualreports.com/Company/1755, (accessed on 12/1/2012). Ba, S. and Pavlou, P. A., 2002, “Evidence of the effect of trust building technology in electronic markets: Price premiums and buyer behavior,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 243-268. Bajari, P. and Hortacsu, A., 2003, “The Winner's curse, reserve prices, and endogenous entry: Empirical insights from eBay auctions,” The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 329-355. Bapna, R., Goes, P. and Gupta, A., 2004, “User heterogeneity and its impact on electronic auction market design: An empirical exploration,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 21-43. Bapna, R., Jank, W. and Shmueli, G., 2008, “Consumer surplus in online auctions,” Information Sys. Res., Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 400-146. Bruce, N., Haruvy, E. and Rao, R., 2004, “Seller rating, price, and default in online auctions,” Journal of Interactive Marketing, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 37-50. Chao, R. M., Lin, M. K. and Chan, C. J., 2006, “A study of the relationship among virtual community, purchase intention and motive of use in online auction-adopting flow experience,” International Journal of Electronic Business, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 247-256. Chris, L., 1998, “Why putting people first must form an essential part of the marketing mix,” Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 39-41. Compeau, L. D. and Grewal, D. 1998, “Comparative price advertising: An integrative review,” Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 257-273. Constantinides, E., 2006. “The marketing mix revisited: Towards the 21st century,” Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 407-438. Edell, J. A. and Staelin, R., 1983, “The 254 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 11, No. 4 (2013) information processing of pictures in print advertisements,” The Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 45-61. Fu, J. R. and Chen, Jessica H. F., 2011, “The impact of seller expertise and a refund guarantee on auction outcome: Evidence from an online field experiment of camera lens market,” International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 187-195. Gefen, D., Karahanna, E. and Straub, D. W., 2003, “Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 51-90. Gollwitzer, P. M., 1999, “Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans,” American Psychologist, Vol. 54, pp. 493-503. Gregg, D. G. and Walczak, S., 2008, “Dressing your online auction business for success: An experiment comparing two eBay businesses,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 653-670. Hakansson, H. and Waluszewski, A., 2005, “Developing a new understanding of markets: The 4ps,” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 110-117. Hou, J., 2007, “Price determinants in online auctions: A comparative study of eBay China and US,” Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 172-183. Hung, M. C., Yang, S. T. and Hsieh, T. C., 2012, “An examination of the determinants of mobile shopping continuance,” International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 29-37. Judd, V. C., 1987, “Differentiate with the 5th P: People,” Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 16, pp. 241-247. Kalakota, R. and Whinston, A. B., 1997, Readings in Electronic Commerce, Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc., MA. Kamins, M. A., Dreze, X. and Folkes, V. S., 2004, “Effects of seller-supplied prices on buyers' product evaluations: Reference prices in an internet auction context,” Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 622-628. Ku, G., Galinsky, A. D. and Murnighan, J. K., 2006, “Starting low but ending high: A reversal of the anchoring effect in auctions,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 90, pp. 975-986. Kwon, O. B., Kim, C.-R. and Lee, E. J., 2002, “Impact of website information design factors on consumer ratings of web-based auction sites,” Behaviour and Information Technology, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 387-402. Lee, G. G. and Lin, H. F., 2005, “Customer perceptions of e-service quality in online shopping,” International Journal of Retail & 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. Distribution Management, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 161-176. Lee, M. Y., Kim, Y. K. and Lee, H. J., 2013, “Adventure versus gratification: Emotional shopping in online auctions,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 47, No. 1/2, pp. 49-70. Lin, M. Q. and Lee, B. C., 2012, “The influence of website environment on brand loyalty: Brand trust and brand affect as mediators,” International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 308-321. McCarthy, E. J., 1960, Basic Marketing: A Managerial Approach, Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin. McEwen, W., 2001, “The power of the Fifth P.,” Gallup Management Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1-2 Melnik, M. I. and Alm, J., 2002, “Does a seller's ecommerce reputation matter? Evidence from eBay auctions,” Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 337-349. Narver, J. C. and Slater, S. F., 1990, “The effect of a market orientation on business profitability,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 20-35. Nikitkov, A. and Darlene, B., 2008, “Online auction fraud: Ethical perspective,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 79, No. 3, pp. 235-244. Ottaway, T. A., Bruneau, C. L. and Evans, G. E., 2003, “The impact of auction item image and buyer/seller feedback rating on electronic auctions,” Journal of Computer Information Systems, Vol. 43, No. 3, pp. 56-60. Palmer, J. W., 2002, “Web site usability, design, and performance metrics,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 151-167. Pavlou, P. A. and Dimoka, A., 2006, “The nature and role of feedback text comments in online marketplaces: Implications for trust building, price premiums, and seller differentiation,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 391-412. Pavlou, P. A. and Gefen, D., 2004, “Building effective online marketplaces with institution-based trust,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 37-59. Pavlou, P. A. and Gefen, D., 2005, “Psychological contract violation in online marketplaces: Antecedents, consequences, and moderating role,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 272-299. Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2004, “Pew internet and American life project,” http://www.pewinternet.org/. Pinker, E. J., Seidmann, A. and Vakrat, Y., 2003, “Managing online auctions: Current business and research issues,” Management Science, Vol. 49, No. 11, pp. 1457-1484. Qureshi, I. and Compeau, D., 2009, “Assessing between-group differences in information Nitin Walia: The Evolution of Online Marketplaces: A Roadmap to Success 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. systems research: A comparison of covariance and component-based SEM,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 33, No.1, pp. 197-214. Reynolds, K., Gilkesonb, J. H. and Niedrichc, R.W., 2009, “The influence of seller strategy on the winning price in online auctions: A moderated mediation model,” In Journal of Business Research, Vol. 62, No. 1, pp. 22-30. Roth, A. and Ockenfels, A., 2002, “Last-minute bidding and the rules for ending second-price auctions: Evidence from eBay and amazon auctions on the internet,” American Economic Review, Vol. 92, No. 4, pp. 1093-1103. Schindler, J., 2003, “Late bidding on the Internet,” unpublished paper. Standifird, S. S., 2001, “Reputation and e-Commerce: eBay auctions and the asymmetrical impact of positive and negative ratings,” Journal of Management, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 279-295. Van-Waterschoot, W. and Van den Bulte, C., 1992, “The 4p classification of the marketing mix revisited,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 56, No. 4, pp. 83-93. Velmurugan, M. S., 2009, “Security and trust in e-Business: Problems and prospects,” International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 151-158. Viswanathan, S., Kuruzovich, j., Gosain, S. and Agarwal, R., 2007, “Online infomediaries and price discrimination: Evidence from the automotive retailing sector,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 71, pp. 89-107. Walia, N., and Zahedi, F. M., 2008, “Web elements and strategies for success in online marketplaces: An exploratory analysis,” ICIS 2008 Proceedings. Walia, N., and Zahedi, F. M., 2013, “success strategies and web elements in online marketplaces: A moderated-mediation analysis of seller types on ebay,” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. 60, No. 4, pp. 763-776. Wilcox, R. T., 2000, “Experts and amateurs: The role of experience in Internet auctions,” Marketing Letters, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 363-374. 255 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Nitin Walia is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Accounting/Information Systems at Ashland University, Oh - USA. He received his PhD degree in Information Systems from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in 2010. He also holds M.S. degrees from Oakland University, MI and Pune University, India. His research interests are healthcare delivery systems, virtual worlds, online marketplaces, web-design interface issues, and open source software adoption and development. He is also working on issues related to providing medical services through a virtual world. He has received a number of research grants and award for teaching. His work has been published (or forthcoming) in IEEE Transactions of Engineering Management and presented in several national and international conferences. (Received February 2013, revised February 2013, accepted August 2013) 256 International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 11, No. 4 (2013) APPENDIX – A Variables Observations Dependent Variable Sale Promotion (Website Richness) Pictures Placement (Timing Strategies) Weekday ending (Mon-Thur) Bidding interval Price (Pricing Strategy) Starting Bid (£) Last Bid amount (£) People (Seller Trust) Positive feedback (seller reputation) Seller age (months) Seller type (business seller) Number of bids (control variable) Product characteristics Car age (years) (control variable) Engine size (cc) (control variable) 1. Sale 2. Bids (control) 3. Pictures 4. Weekday 5. Bid Interval 6. Starting Price 7. Last Price 8. Market-mediated 9. Seller reputation 10. Seller Age 11. Seller type 12. Car age(control) 13. Engine Size (control) 1 1 .47 .10 .11 -.04 -.20 -.17 .05 .12 -.02 .14 .09 -.11 Table A1: Descriptive statistics UK-I Mean Stdev or % 1,255 UK-II Mean or % 1,140 36% 44% 5.3 4.7 6.9 3.7 82% 6.2 2.7 85% 6.4 2.4 6,363 8,711 12,543 13,221 1,238 1,935 2,714 2,881 138 24 13% 9.9 310.77 15.3 1293.9 390.1 10.4 407.6 140 28% 7.5 7.8 2,322 5.4 1,025 11 1,935.6 1.13 634 Table A2: Correlations matrix (n=2395) 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 .20 .05 -.01 -.22 -.05 .09 .13 -.12 .18 -.06 -.01 1 -.01 .07 -.06 -.02 .01 -.04 .05 .12 -.07 .05 Stdev 8 9 10 9.7 11 12 13 1 -.04 1 -.17 .16 1 -.20 .18 .92 1 -.02 .06 .03 .06 1 .06 -.04 -.06 -.04 -.05 1 -.02 .12 -.10 -.14 -.08 .01 1 .11 -.03 -.10 -.06 -.08 .29 .07 1 .16 -.09 -.33 -.40 .04 -.03 .05 -.09 1 -.16 .14 .40 .46 .02 .01 -.07 -.04 -.06 1 Nitin Walia: The Evolution of Online Marketplaces: A Roadmap to Success APPENDIX – B Table B1: Comparison of UK-I and UK-II UK‐I : Seller Feedback Score UK‐II : Seller Feedback Score 257