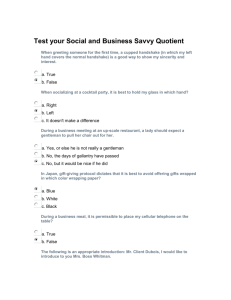

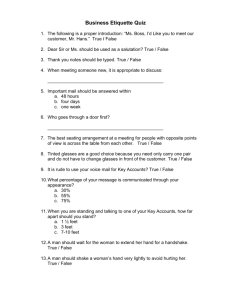

MANAGEMENT SCIENCE

advertisement