The Legal Implementation of Coastal Zone Management: The North

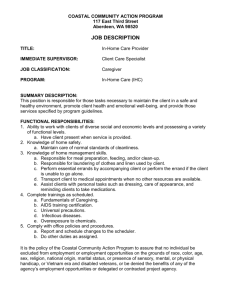

advertisement