chapter 9 - EEC-Anglo EEC

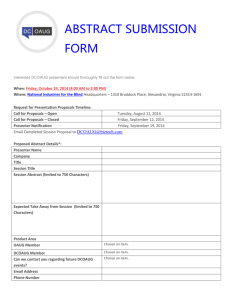

advertisement