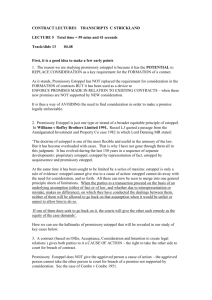

Promissory Estoppel, Contract Formalities, and Misrepresentations

advertisement