Skeleton – Counsel for the Respondents

advertisement

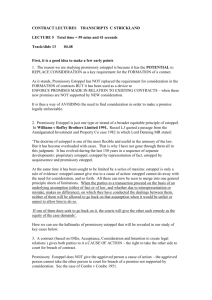

IN THE SUPREME COURT ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL BETWEEN: MCDOUGALLS LTD Appellant -vBRANSON Respondent COUNSEL’S SKELETON ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF THE RESPONDENT This skeleton argument addresses the both grounds of appeal. First, whether the Court of Appeal erred in law in holding that Branson can rely upon the doctrine of estoppel. Second, whether McDougall’s promise is otherwise actionable and can found a claim for expectation losses. First, it is submitted that the doctrine of promissory estoppel should function in this case. 1. There is no principled reason to disallow promissory estoppel from creating a cause of action in order to avoid unconscionable results 1.1. The distinction between extinguishing a right and creating a right is a formality. In practice they both effect a change in the legal relationship between parties. (Waltons Stores (Interstate) Ltd v Maher (1988) 164 CLR 387 [29] (Brennan J)) 1.2. It is incoherent to allow an estoppel to form part of a cause of action but not be a cause of action in itself (as in the analogous case of Amalgamated Investment & Property Co Ltd v Texas Commerce International Bank Ltd [1982] 1 QB 84 (CA) 131) 2. Allowing promissory estoppel to be a cause of action does not destroy the doctrine of consideration. 2.1. Contrary to Combe v Combe [1951] 2 KB 215 (KB) 220, allowing promissory estoppel to create a cause of action would not overrule the requirement of consideration to enforce contractual agreements. 2.2. Promissory estoppel would merely exist as an alternative basis to bring a cause of action, akin to founding an action in tort. 3. It is unprincipled to disallow an estoppel from being a cause of action simply because it does not relate to an interest in land. 3.1. Proprietary estoppel and promissory estoppel have a common basis in equity. They have been treated as mere facets of the same general principle in the common law, as summarized in Waltons Stores v Maher [28] – [30] (Mason CJ and Wilson J). 3.2. There has been no compelling principled reason given in common law why proprietary estoppel can give rise to a cause of action while promissory estoppel cannot. 4. Alternatively, the doctrine of consideration should be dispensed with in light of modern developments 4.1. The doctrine no longer fulfils its intended function in light of Williams v Roffey Brothers & Nicholls (Contractors) [1991] 1 QB 1 (CA) 15-16, 18. 4.2. The doctrine is divorced from modern commercial reality. It is easily and widely circumvented by nominal payment of a peppercorn or by making the contract under seal Second, it is submitted that the Court of Appeal did not err in law and that McDougall’s promise is actionable and gives rise to full expectation damages. 5. First, there is an oral contract between Kroc, as McDougall’s agent, and Branson, which has been breached. 4.1. The requirements for a valid contract are met here. 4.3. McDougall’s have entered a contract with Branson, which they then breached making them liable for Branson’s expectation losses under Hadley v Baxendale (1854) 9 Ex. 341, 355. 6. Second, even if there is no contract, the statement made by Kroc amounts to negligent misrepresentation. 5.1. Under the Hedley Byrne principle and in line with Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] Q.B. 801, 819- 821 McDougall’s owed Branson a duty of care which they negligently broke. 5.2. A statement of future intent is a misrepresentation if the representor had no intention of carrying out the stated intent (Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) L.R. 29 Ch. D. 459, 479) 7. Third, even if the statement does not amount to negligent misrepresentation and there is no contract, it does amount to fraudulent misrepresentation under the tort of deceit. 7.1. In line with Derry v Peek (1889) 14 App. Cas. 337, 343-345 there are, in the present case, all the constituents of fraudulent misrepresentation. 7.2. In line with the judgement in East v Maurer [1991] 1 WLR 461 at 467 the lost future profits are recoverable. 8. For these reasons, both grounds of appeal should be dismissed. Shang Koh & Alice Francis Counsel for the Respondent 4 November 2014