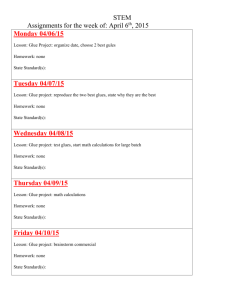

HB Fuller - Honduras +

advertisement

From “Honduras This Week” http://www.marrder.com/htw/aug96/national.htm A Fear of Life By W. E. GUTMAN Thousands of homeless children in Central America prowl the streets, scavenging to stay alive and sniffing shoe glue to forget they were ever born. Selling amnesia and death, glue manufacturers conspire in an ever-widening cycle of infanticide. In Guatemala it's cobbler's glue. In Honduras it's Resistol. In Mexico it's Activo, a potent industrial solvent. When inhaled, all devour sinuses and lungs, produce hallucinations, destroy vital organs, cause irreversible brain damage and ultimately kill. And yet, life on the street drives thousands of Central American children to surrender to these toxins in order to calm their spirit, to quiet their hunger, to embolden them against the perils of homelessness and "to forget," as 13-year-old Luisa, who has been sniffing glue for the past three years, explains. "When I feel nothing I feel good." Inhalant use, especially glue-sniffing, is now pandemic among street children. Orphaned, rejected or abused, often abandoned by parents too poor to feed themselves, they seek shelter under bridges, in doorways and garbage dumpsters and face a future of larceny, prostitution, teenage pregnancy, chronic illness and early, often violent, death. They will sell themselves for a meal, a hot shower, a clean bed, the next bag of glue. YOUNG VICTIMS Amanda, a fourteen-year-old Nicaraguan mother, sniffed glue during her two pregnancies. The glue is laced with toluene, a neurotoxin. Her first daughter was stillborn. Her second was born prematurely and suffers from seizures. Amanda abandoned her and is back on the streets. Ten-year-old Sergio sleeps in a small cardboard box. Every morning he folds up his "home," straps it to his back and moves to another part of town. He has been cruising the streets of Tegucigalpa for nearly half his life. He sniffs glue to stop feeling hungry. His eyebrows and patches of hair were shaved recently to remove the glue a policeman poured on his head in a fit of rage. Some of the glue ran into one of his eyes, burning the cornea. "A shaved head brands him as an addict," says Bruce Harris, the executive director of Covenant House Latin America, known locally as Casa Alianza, an organization that champions the cause of street children. "He inspires no pity, only suspicion and disgust. He is now fair game for every self-righteous enforcer of civic morality or public order. He is the new pariah on the block." This perception, bolstered by indifferent or openly hostile governments, has inspired a wave of bloodletting against street children. Once reactive and sporadic, intimidation, threats, beatings, rapes, torture and summary executions at the hands of city and national police are now routine. These indignities have since come to international attention largely through Harris's tireless efforts. Casa Alianza is now prosecuting 200 cases against 125 policemen, 48 army personnel and several persons "in plain clothes" charged with horrific acts of brutality against children. BUSINESS FIRST Viewed as "vermin," unwanted and unloved, street children are invariably accused of being "bad for the country." But they are far from being bad for business. Sales of the glue they use continue to boost the profits of multinational corporations, incrementally increasing as the numbers of street children rise. The St. Paul, Minnesota-based H. B. Fuller Co., for example, commands such a prominent position in the glue market that its Resistol brand has become the imprimatur of glue-addicted street children, the Resistoleros. H. B. Fuller is quick to point out that it is breaking no laws. It also steadfastly denies responsibility for the chronic illnesses and deaths its products continue to exact. After learning of the imminent airing of an "NBC Dateline" TV exposé largely based on evidence gathered by Harris and his regional directors, H. B. Fuller's board declared in 1992 that the company would "discontinue production of solvent adhesives where they are known to be abused." The proclamation elicited an outpouring of praise from the media and others. An update by NBC a year later revealed that H. B. Fuller had then boasted to its shareholders that an "insignificant fraction" of the Resistol stock had been removed from shelves. ADDICTING EUPHORIA Toluene, a common constituent in shoe glue, can best be compared to opiates -- and to certain snake venoms that attack the central nervous system. The euphoria it produces results from toxic effects on brain cells and other organ tissue. Reacting to this onslaught, the brain is flooded with soothing endorphins which temporarily dull pain, hunger and cold. Withdrawal symptoms are swift and unmerciful. A sudden and frightening onset of lucidity leads to more glue sniffing and, in the long run, to addiction. Insisting H.B. Fuller's are "good products put to bad use," company chairman Tony Andersen says "the problem is not our product." He blames society and the children. Curiously, H. B. Fuller has long understood the potential value of non-solvent-based adhesives. Its 1980 Annual Report states: "Growing concern over the use of environmentally safe adhesives and sealants is creating market opportunities for [our] line of hot melt and water-based adhesives, a better alternative to solvent-based products." Hot melts require no solvents and are applied with a glue gun. While H. B. Fuller has been letting this "market opportunity" go unexploited, the company has spent several million dollars in publicity campaigns designed to exculpate itself from allegations by international watchdog organizations ranging from predation to negligent homicide. Predictably, the company has since become the target of a precedent-setting lawsuit in the death of Jesus Linares Polanco, a 14-year-old Guatemalan street child addicted to Resistol. Brought on by the boy's family and currently being heard in the U.S. District Court of St. Paul, Minnesota, charges include failure to warn users of the products's addictive properties, failure to add available inhibitors and wrongful death. H. B. Fuller seeks to have the case dismissed on the grounds that Resistol is manufactured by its Guatemalan subsidiary and that the parent company is [therefore] immune from prosecution. NOT ENOUGH While the company's longtime German competitor, Henkel, voluntarily pulled its solvent-based adhesives out of Central America in September 1994, H.B. Fuller switched the sovent in its adhesive from toulene to cyclohexane for its commercial line and began selling cyclohexane contact cement in Costa Rica in January 1995. Suspected of being both a carcinogen and a mutagen, cyclohexane is on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Superfund List of hazardous toxins. "The difference between toluene and cyclohexane," says Oklahoma City medical examiner, Dr. Tim Rohring, "is like the difference between a .44 [caliber] and a .357 magnum. They're both deadly." H. B. Fuller has also been experimenting with Bitrex, a bitter additive used to discourage children from ingesting household chemicals. Why would anyone add a taste inhibitor to a product that is inhaled, not swallowed, is unclear. "Street children know shoe glue tastes foul," says Harris. "They may be desperate, but they're not stupid. They have no intention of eating it. Besides, Bitrex does not deter inhalation." Asked why H.B. Fuller refused to add such deterrents as mustard oil (allyl isothiocyanate, or AITC) to cobbler's glue, Dick Johnson fired back, "that's a bandaid solution. AITC is useless." Not so. AITC has been successfully used by the Testor Corporation to end the model airplane gluesniffing epidemic that swept the United States in the 1960s. H.B. Fuller has failed to research the efficacy of mustard oil. But the company continues to lobby hard against legislation in Honduras and Guatemala that would mandate the addition of AITC to Resistol. Instead, H.B. Fuller has told shoemaker syndicates that mustard oil is a carcinogen, a claim dismissed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Only a minute amount of AITC is needed to deter inhalation. SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY "While the use of inhalants by Latin American street children is not the cause of the social ills preying upon this vulnerable population," says Harris, "escaping into a drug-induced stupor only compounds the risk of permanent mental damage and encourages the escalation of risky behavior that further threatens their welfare and life. We must put in place an effective social policy to end these inequities and stop the producers who are making money off the backs of homeless children." At the conclusion of an H.B. Fuller stockholders' meeting in a posh San José, Costa Rica hotel, Tony Anderson waved off a request for an interview, saying, "Talk to Kissling. He's in charge." H. B. Fuller CEO Walter Kissling, a Costa Rican, says, "we're not in the business of killing children. We're just in business." When asked whether that meant H.B. Fuller's policy is "Let the buyer beware," he shrugged, looked at his watch and ended the interview. It has been 17 years since cases of severe injury and death from solvent adhesives were first reported among Central American street children. Countless impassioned appeals and strongly worded injunctions have failed to touch H.B. Fuller. The company continues to market products long since banned in the United States, products that are sold to children who continue to partake, get sick and die. These children are in search of a final exit from their wretched existence. H.B. Fuller, patron of the arts and protector of the environment, obliges. A Connecticut-based journalist, W. E. Gutman is currently on assignment in Central America.