DECISION MAKING IN SCHOOLS - Wikispaces

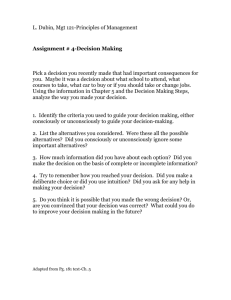

advertisement