1 Public Goods and Common Resources

advertisement

1 Public Goods and Common Resources

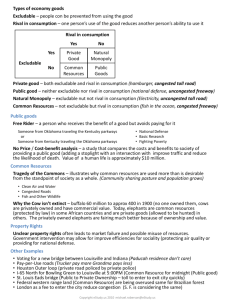

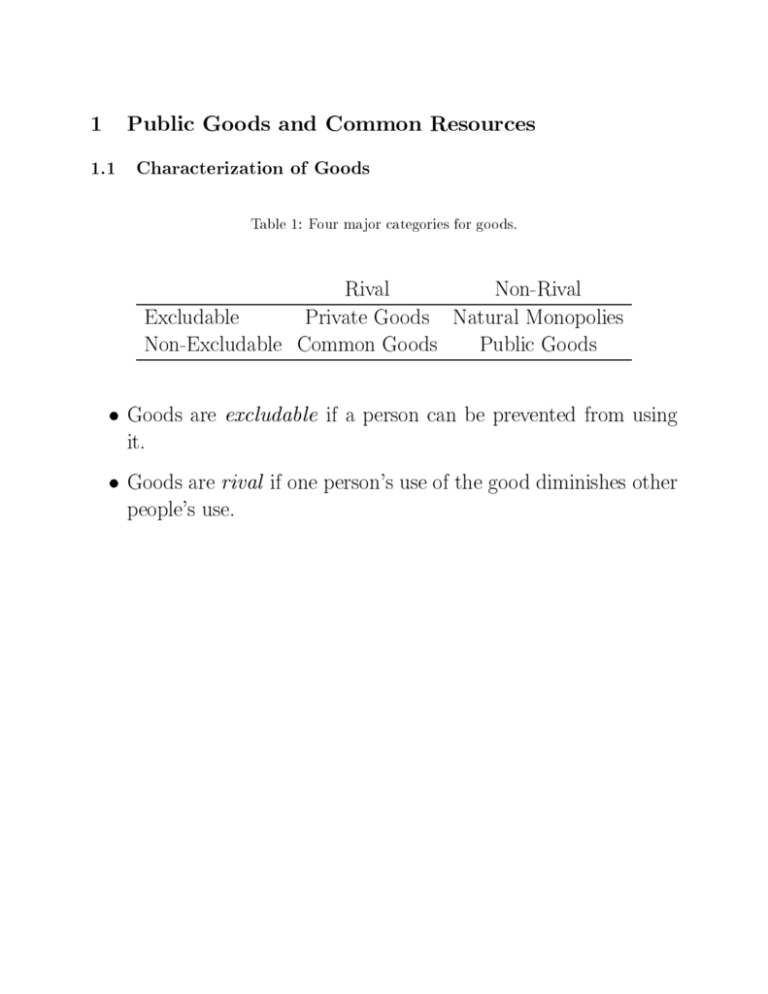

1.1 Characterization of Goods

Table 1: Four major categories for goods.

Rival

Non-Rival

Excludable

Private Goods Natural Monopolies

Non-Excludable Common Goods

Public Goods

Goods are excludable if a person can be prevented from using

it.

Goods are rival if one person's use of the good diminishes other

people's use.

Therefore, we have four main categories for goods:

1. Private goods are both excludable and rival. Examples include ice-cream cones, clothing, congested toll roads, and so

on.

2. Public goods are neither excludable nor rival. Examples include national defense, knowledge, uncongested nontoll roads,

and so on.

3. Common resources are rival but not excludable. Examples

include sh in the ocean, the environment, congested nontoll

roads, and so on.

4. Natural monopolies are excludable but not rival. Examples include re protection, cable tv, uncongested toll roads,

ideas, and so on.

1.2 Private Goods

The most important lesson of this class so far is summarized by

Paul Romer as follows.

\If you take traditional private goods that are excludable and rival, we know what the best institutional

arrangement is: strong property rights and anonymous

markets. That's all you need. This is a remarkably important insight that economists must still communicate

to the rest of the world. If people understood it, there

would not be so much resistance to pricing roads, pollution or water in agriculture. Non-economists are still

slow to understand how powerful the price mechanism is

for allocating and producing rival goods."

For more, see

http://www.stanford.edu/~promer/Int re macro.html.

1.3 Public Goods

The dening characteristic of public goods is that everyone can

use them freely. Therefore, they possess a possibility of the freerider problem: When public goods cost money to produce, people who use them do not necessarily pay for them. Therefore,

there is a room for government. Somebody has to collect the

money that is needed to pay for public goods.

Examples of public goods:

1. National defense. In 1999 the U.S. federal government spent

a total of $277 billion on national defense. It is doubtful that

private people would voluntarily raise this amount.

2. Basic research. Basic research produces general knowledge

that anybody can freely use. On the other hand, specic,

technological knowledge (ideas), can be patented and are

thus (at least partially) excludable.

3. Antipoverty programs. Again, private, voluntary, charity

produces a free-rider problem. Everybody enjoyes when there

are no homeless people on the streets, but not everybody is

willing to pay for it.

4. Airline security. In the U.S., people responsible for screening

passangers are typically paid $5 an hour and trained for a

maximum of 12 hours. In Europe, they are paid $10{15 an

hour and trained several weeks. The dierence is that in the

U.S. the airline security was paid by the airline companies,

while in Europe it was paid by tax-payers.

1.4 Common Resources

Common resources are rival but not excludable. Therefore, they

give rise to a new problem. One must concerned that they are

not overused. This is known as the Tragedy of the Commons

problem: Everybody wants to use the common resource as much

as possible but the result is|since the good is in xed supply|it

will disapper and everybody will lose.

Examples of common resources:

1. Clean air and water.

2. Oil pools.

3. Congested roads.

4. Wildlife.

Question: Why are elephants almost extinct but cows are not?

Answer: People have property rights over cows but not over

elephants.

1.5 Club of Rome and Common Resources

According to Thomas Malthus, an 18th century economist, the

population increases exponentially but the amount of food only

linearly. Therefore, population will always expand to the limit of

subsistence and will be held there by famine, war, and ill health.

In the 1970's, the Club of Rome published a report The Limits to Growth. This report focused on hypotheses derived from

a computer model of the interaction of various global socioeconomic trends; it projected a Malthusian vision in which the

collapse of world order would result if population growth, industrial expansion, and increased pollution, combined with insufcient food production and the depletion of natural resources,

were to continue at current rates.

To oset these trends, the report called for \a Copernican revolution of the mind," to reevaluate the belief in endless growth

and the tacit acceptance of wastefulness. Besides zero population

growth and a leveling-o of industrial production, the report also

recommended increased pollution control, the recycling of materials, the manufacture of more durable and repairable goods, and

a shift from consumer goods to a more service-oriented economy.

Question: Was the Club of Rome right?

The Club of Rome predicted that \the world in 2000 will be

more crowded, more polluted, less stable ecologically: : : and the

world's people will be poorer in many ways than they are today."

According to biologist Paul Ehrlich (Stanford University): \If

I were a gambler, I would bet even money that England will

not exist in the year 2000" and \in the course of the 1970s the

world will experience starvation of tragic proportionshundreds of

millions of people will starve to death."

In 1980, Julian Simon (Ph.D., Economics, University of Chicago;

Professor of Economics, UIUC) bet Paul Ehrlich $1,000 that ve

resources would be less expensive in 10 years. Paul Ehrlich could

choose the goods, and if a basket of these goods was more expensive (in real terms) he would win. Question: What happened?

Ehrlich lost: 10 years later every one of the resources had declined in price by an average of 40 percent.

For more information, visit

http://www.cba.uiuc.edu/seppala/econ101/

1.6 The Truth about the Environment

This section draws on work by Bjorn Lomborg who is a statistician at the University of Aarhus, Denmark. He once held what

he calls \left-wing Greenpeace views." In 1997, he set out to

challenge Julian Simon and found that the data generally supported Simon.

According to Lomborg, environmentalists, led by Paul Ehrlich

of Stanford University have developed a sort of \litany" of four

big environmental fears:

1. Natural resources are running out.

2. The population is ever growing, leaving less and less to eat.

3. Species are becoming extinct in vast numbers: forests are

disappearing and sh stocks are collapsing.

4. The planet's air and water are becoming ever more polluted.

Human activity is thus deling the earth, and humanity may end

up killing itself in the process.

Responses to these fears:

1. See previous section.

2. More food is now produced per head of the world's population than at any time in history. Fewer people are starving.

In addition, there has never been a famine in a democracy.

3. Although species are indeed becoming extinct, only about

0.7% of them are expected to disappear in the next 50 years,

not 25{50%, as has so often been predicted.

4. According to empirical studies, clean air and water are luxury

goods. Once the country GDP/capita reaches the level of

$5,000, the people start paying attention to the environment

and the quality of air and water improves. Therefore, the

economic growth is the best way to improve the environment.

For more, see

http://www.cba.uiuc.edu/seppala/econ101/envrnmnt.html.