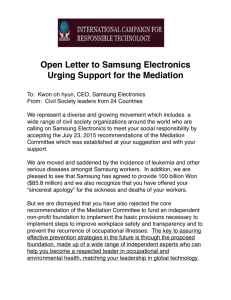

SAMSUNG - Asia Monitor Resource Center (AMRC)

advertisement