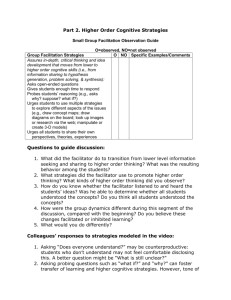

Facilitator's Toolkit

advertisement