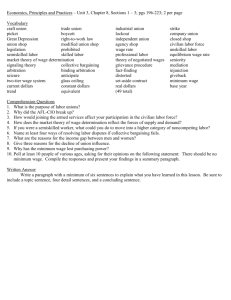

Developing & Maintaining A Sound Compensation Program

advertisement