introduction to LD.

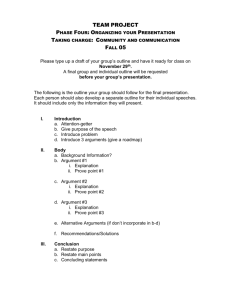

advertisement