The Past Makes the Present Meaningful: Nostalgia as an Existential

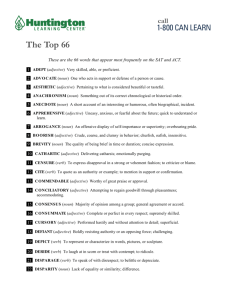

advertisement