The Future of Public and Nonprofit Strategic Planning in the United

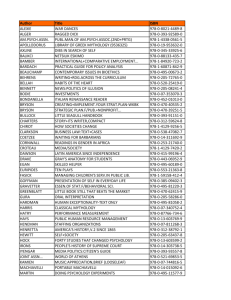

advertisement