Indonesia's Fuel Subsidies: Action plan for reform

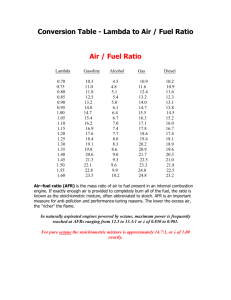

advertisement