WRITING EFFECTIVE LAB REPORTS

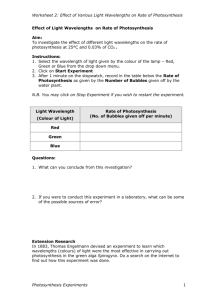

advertisement

By the end of this workshop, you’ll be able to • • • Create a lab report that adheres to the IMRAD format. Apply pre-writing, writing, and re-writing strategies in order to develop well-structured, objective, clear, and concise scientific documents. Locate various forms of on-campus writing support to help you with your next assignment. © 2013 The Writing Centre, Student Academic Success Services • Essay writing • Lab report writing • Thesis writing • Grammar • General writing tips sass.queensu.ca 613.533.6315 Stauffer Library An Overview What does science writing do? Writing effective lab reports Tackling a writing project in the sciences Principles of science writing A brief introduction Communicate results and their importance Be accurate and precise Allow for repeatable experiments Demonstrate the author’s understanding of theories, phenomena, and procedures behind the data Show that the author can think critically Indicate that the author can communicate effectively in a particular discipline The IMRAD structure 1) The title should not be too vague or too short • Rule of thumb: 10-12 words may relate to the main objective, species involved, and location (if relevant) may be derived from the x/y axis of the main figure in the lab report Examples: Wolverine (Gulo gulo) hunting behaviour in the Claire Lake watershed, Yukon Territory includes main topic, species involved, and location Heart Mountain fault systems: architecture and evolution of the collapse of an Eocene volcanic system, northwest Wyoming includes location, geological feature, and age Provides the right amount of detail Avoids jargon and abbreviations Avoids wasted words • A study of . . . / An investigation of . . . / Observations on . . . • A, an, and the (at the beginning of the title) 2) The Abstract Summarizes the purpose of the study, the methods, the results, and the significance of the results Is a single paragraph that stands alone Is written in complete sentences • Usually devotes one sentence each to purpose, methods, results, and significance 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Reason for writing – What is the importance of the research? Why would the reader be interested in the work? Problem – What problem does this work attempt to solve? Methodology – What models or approaches were used in the study? Results – What specific data help us to understand the results of the project? Implications – How does this work add to the body of knowledge on the topic? Sample Abstract This study was undertaken to determine the wavelengths of light that are most effective in promoting photosynthesis in the aquatic plant Elodea canadensis since some wavelengths are generally more effective than others. Rate of photosynthesis was determined at 25ºC, using wavelengths of 400, 450, 500, 550, 600, 650, and 700 nm and measuring the rate of oxygen production for 1-h periods at each wavelength. Oxygen production was estimated from the rate of bubble production by the submerged plant. We tested 4 plants at each wavelength. The rate of oxygen production at 450 nm (approximately 2.5 ml O₂/mg wet weight of plant/h) was nearly 1.5x greater than that at any other wavelength tested, suggesting that light of this wavelength (blue) is most readily absorbed by the chlorophyll pigments. In contrast, light of 550 nm (green) produced no detectable photosynthesis, suggesting that light of this wavelength is reflected rather than absorbed by the chlorophyll. (from Jan A. Pechenik, A Short Guide to Writing about Biology, 2010) References to other works Information not contained in the report itself Definitions of terms HINT: For more sample abstracts, take a look at journals in your field. Section Purpose Answers these questions Introduction Explains central question Gives context for the investigation Cites any relevant literature Names chosen approach States primary results What did you do? Why did you do it? Who else has done related work? How did you do it? What happened? Materials and Methods Details the experimental procedure step by step How could someone else replicate your experiment? Results Reports, in detail, the results of the investigation What actually happened? Discussion Comments on the significance of the results Suggests refinements, applications Offers possibilities for further study Did the experiment do what you expected it to? Why or why not? How might the experiment be improved or adapted? What next? 3) The introduction introduces the topic and conveys why it is important or interesting provides a short review of relevant, current research • also explains any theories or formulas readers need to know is sometimes understood as a miniliterature review OR a mini-essay that leads up to your statement of purpose A good introduction also clearly states the objective of the experiment. Example: The purpose of this experiment was to identify the specific element in a metal powder sample by determining its crystal structure and atomic radius. These were determined using the DebyeSherrer (powder camera) method of X-ray diffraction. HINT: The objective can appear at the beginning or end of the introduction. general statement more specific statements specific research objectives Example: It is well known that plants can use sunlight as an energy source for carbon fixation (Ellmore and Reed 1993). However, all wavelengths of light need not be equally effective in promoting such photosynthesis. Indeed, the green coloration of most leaves suggests that wavelengths of approximately 550 nm are reflected rather than absorbed so that this wavelength would not be expected to produce much carbon fixation by green plants. During photosynthesis, oxygen is liberated in proportion to the rate at which carbon dioxide is fixed (Ellmore and Reed 1993). Thus, relative rates of photosynthesis can be determined either by monitoring rates of oxygen production or by monitoring rates of carbon dioxide uptake. In this experiment, we monitored rates of oxygen production to test the hypothesis that wavelengths of light differ in their ability to promote carbon fixation by the aquatic plant Elodea canadensis. (Pechenik 2010) The essential elements: ◦ Which materials and equipment did you use? Be as detailed as possible. ◦ How did you physically set up the experiment? ◦ What was the experimental design? e.g., treatments, controls, etc. ◦ What was the step-by-step process of the experiment? Remember: Readers must be able to replicate your experiment based on this information. 5) Results includes several sentences that summarize the results of the study (also known as Observations or Measurements) a description of what happened Start with the most important finding, and then move on to secondary ones. includes figure(s), graph(s), and/or table(s) 5 Series 1 Series 2 0 Series 3 A B C D DOs: Do use the past tense. Do write in full sentences, not point form. Do use charts/graphs when possible. Do avoid redundancy between text and graphs. DON’Ts: o o o o Don’t omit any relevant results. Don’t include irrelevant results. Don’t include any references. Don’t forget axis labels and units. Example: Each time we subjected sample A to this pressure, we heard a loud explosion inside the anvil. Despite this, we were able to recover the entire samples, which were still surrounded by their pyrophilite rings. They were disk-shaped, with a diameter 1mm and height 0.1 mm. They were brittle, and cracked and broke with handling, giving rise to faces with sharp dendrites. The samples became transparent, with an amber or reddish-brown hue. A small amount of black powder remained on the surface and on the boundary of the pyrophilite sample. (from David Porush, A Short Guide to Writing about Science, 1995) 6) Discussion analyzes/interprets the results of the study; provides possible explanations suggests sources of errors and how the experiment could be improved provides support from sources may suggest how the experiment could be applied Example 1: The discrimination of worker bees against worker-laid eggs could result from three possible factors: the workers somehow “knew” the relatedness of eggs; they preferred queen-laid over worker-laid eggs; or they detected colony odors despite the double screen we used to separate them. (Pechenik 2010) Example 2: Since none of the samples reacted to the Silver foil test, therefore sulfide, if present at all, does not exceed a concentration of approximately 0.025 g/l. It is therefore unlikely that the water main pipe was the result of sulfide-induced corrosion. (from “The Lab Report,” Writing at the University of Toronto website) One possible arrangement of the Discussion: 1) Discuss your most significant result and the accuracy of your hypothesis in the first paragraph. 2) Analyze the data. 3) Explain problems in the data or suggest improvements to your experimental process. 4) Make conclusions with regard to your hypothesis. 5) Create connections between your conclusions and larger issues. An example of how to explain problems in the data: Although the water samples were received on 14 August 2012, testing could not be started until 10 September 2012. It is normally desirable to test as quickly as possible after sampling in order to avoid potential sample contamination. The effect of the delay is unknown. (“The Lab Report”) Making good use of other studies in the Discussion • • To integrate sources effectively, be sure that the studies you use are relevant to your experiment. Use citations, not quotations, when you are referring to others’ research. Example: I find the small number of species represented in our sample surprising, since the pond is fed by several streams that might be expected to introduce a variety of different species into it, assuming that the streams are not polluted. It appears that the conditions in the pond at the time of our sampling were especially suitable for one species in particular out of all those that are most likely to have access to it. Perhaps the physical nature of the pond is such that the number of niches is small, in which case competition would become very keen; only one species can occupy a given niche at any one time (Ricklefs and Miller 2000). The reproductive pattern of the fishes might also contribute to the observed results. Possibly Lepomis macrochirus, the dominant species, lays more eggs than the others, or perhaps the young of this species survive better, or prey on the young of other species. (Pechenik 2010) 7) Conclusion may or may not be included in the report • If not, put this information in a short summary paragraph at the end of the Discussion. provides an answer to the problem raised in the Introduction concisely restates the result (i.e., what you know) with a brief justification 8) References Some tips for handling references Always acknowledge sources of specific information with citations in the text of your report and references at the end. General knowledge = material discussed in class Doesn’t need to be cited Avoid paraphrasing the source too closely: use your own words. Referencing Styles In-text references: The name-and-year system • (Semple and Messenger 2005). The alphabet-number system: numbers each reference in an alphabetical list . . . attributed to cardio-pulmonary distress⁷. . . . attributed to cardio-pulmonary distress [7]. The citation-order system: • Numbers each reference sequentially • • 1 = first reference in the report, 2 = second, . . . In-text references look like the alphabet-number system above. The References page provides the full publication information for the source. Semple I, Messenger D. 2004. False positives for the defibrillator: the effects of stress on cardio-pulmonary distress in emergency room patients. Emergent care. 201(3): 147-156. Tips on documentation: Check with your instructor or TA to find out the required style. If no particular style is required, use a source’s References page as a guide. Above all, be consistent. Strategies that work Section Purpose Answers these questions Introduction Explains central question Gives context for the investigation Cites any relevant literature Names chosen approach States primary results What did you do? Why did you do it? Who else has done related work? How did you do it? What happened? Materials and Methods Details the experimental procedure step by step How could someone else replicate your experiment? Results Reports, in detail, the results of the investigation What actually happened? Discussion Comments on the significance of the results Suggests refinements, applications Offers possibilities for further study Did the experiment do what you expected it to? Why or why not? How might the experiment be improved or adapted? What next? (from James Hanmer, http://jwhanmer.blogspot.ca/2009/11/mindmap.html) You don’t have to start with the Abstract and work straight through to the Conclusions. A more effective model 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Materials and Methods Results Introduction Discussion Conclusions Abstract (from Margot Northey and Patrick von Aderkas, Making Sense: Life Sciences, 2011) ¼ to ¾ of a double-spaced page (with some variations) best to avoid short transitional paragraphs Each paragraph must have a single controlling idea. ◦ works best as the topic (first) sentence of the paragraph ◦ Example: Two standards were used to measure these changes. REMEMBER: 1 paragraph = 1 idea Transitions needed: The energy needs of a resting sea otter are 3 times those of terrestrial animals of comparable size. The sea otter must eat about 25% of its body weight daily. Sea otters feed at night as well as during the day. (Pechenik 2010) With transitions: The energy needs of a resting sea otter are 3 times those of terrestrial animals of comparable size. To support such a high metabolic rate, the sea otter must eat about 25% of its body weight daily. Moreover, sea otters feed continually, at night as well as during the day. HINT: Don’t put a transition to a new idea at the end of a paragraph. Identify and revise organizational problems in this paragraph: Singer and Nicolson found, in 1972, that cell membranes are composed of a lipid bilayer in which proteins are randomly distributed. Scientists discovered that biomembranes have heterogeneous regions called microdomains or rafts. Clusters of sphingolipids and cholesterol typify these zones. Cell membranes have been the subject of much research for many decades. But developments in the field since Singer and Nicolson’s discovery in 1972 are even more significant. (based on a sample in Northey and von Aderkas 2011) One possible revision: Researchers have studied cell membranes for many decades (topic sentence). In 1972, Singer and Nicolson found that cell membranes are composed of a lipid bilayer in which proteins are randomly distributed (transitional phrase). Later, biochemists discovered that biomembranes have heterogeneous regions called microdomains or rafts, typified by clusters of sphingolipids and cholesterol (transitional word, more precise subject, combined sentences). But developments in the field since Singer and Nicolson’s discovery in 1972 are even more significant. . . . (transition moved to start of new paragraph) And how to apply them You may not be allowed to use the firstperson pronouns “I” and “we.” HINT: Always check with your marker. Learn how and when to use the passive voice. Active: The researcher diluted the samples with 100 ml of H20. Passive: The samples were diluted with 100 ml of H20. HINT: Some experts recommend the passive voice for Materials and Methods and Results, but not for the Introduction, Discussion, or Conclusions. Avoid generalizations. Focus on the particular study at hand. Avoid vague language. NOT “Several of the rods got very cold.” BUT “Twenty of the rods cooled to -20º C.” Use plain language to support jargon and discipline-specific vocabulary. Avoid wordiness and elaborate expressions. ◦ NOT “make an assumption” BUT “assume” ◦ NOT “at this point in time” BUT “now” Limit use of noun clusters. ◦ NOT experiment plan revision summary ◦ BUT summary of the revised experiment plan Allow for a degree of uncertainty. Avoid definitive conclusions. ◦ Results “suggest,” “indicate,” or “are significant.” ◦ Results do NOT “prove,” “show,” or “demonstrate.” Avoid using the overly familiar and informal personal pronoun you. You can see . . . Smith’s findings suggest that . . . Avoid contractions in formal writing. can’t cannot isn’t is not doesn’t does not Avoid colloquialisms (informal language). a lot of many does a good job effectively sass.queensu.ca/writingcentre/ 613.533.6315 Queen’s Learning Commons Main Floor, Stauffer Library Upcoming Writing Centre Workshops Writing Effective Thesis Statements Oct. 9, 1:30-2:20 p.m., Stauffer 121 Constructing Clear and Focused Paragraphs Oct. 23, 2:30-3:20 p.m., Stauffer 121 Using Sources Effectively and Avoiding Plagiarism Oct. 29, 10:30-11:20 a.m., Stauffer 121 Perfectionism in Writing Nov. 14, 11:30 a.m.-12:20 p.m., Stauffer 121 This workshop makes use of material from the following sources: • • • • • Hanmer, James, http://jwhanmer.blogspot.ca /2009/11/mindmap.html “The Lab Report,” Writing at the University of Toronto website, www.writing.utoronto.ca Northey, Margot and Patrick von Aderkas, Making Sense: Life Sciences, 2011 Pechenik, Jan A., A Short Guide to Writing about Biology, 2010 Porush, David, A Short Guide to Writing about Science, 1995