nikkeistories_study guide2015

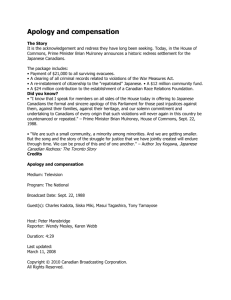

advertisement