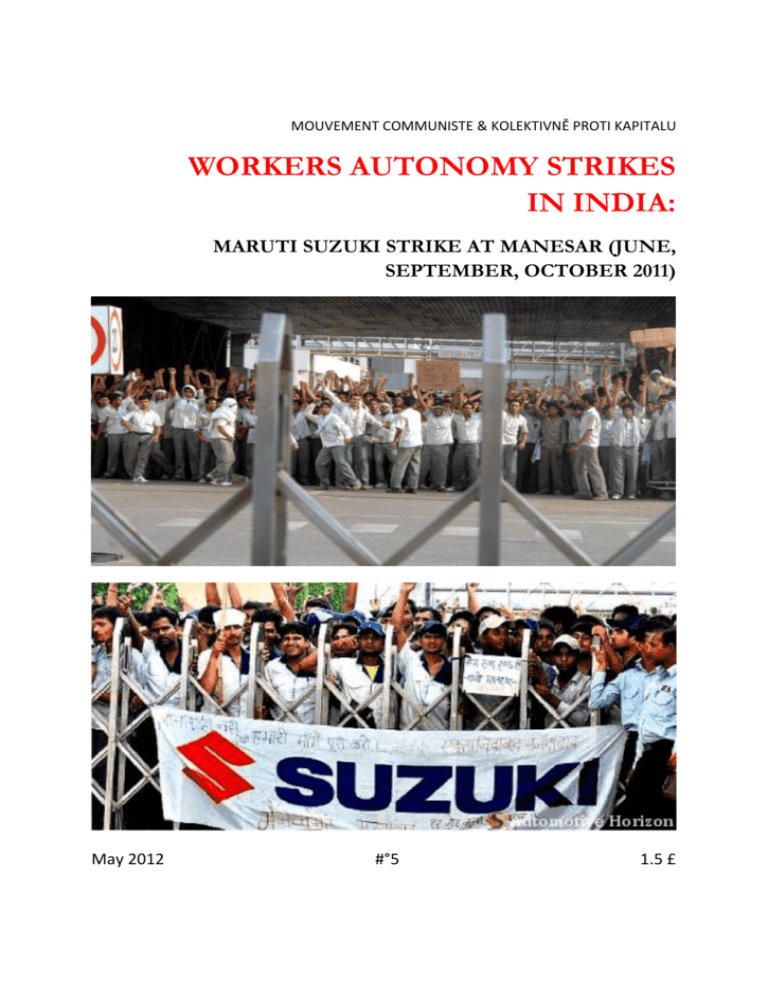

WORKERS AUTONOMY STRIKES IN INDIA: MARUTI SUZUKI

advertisement