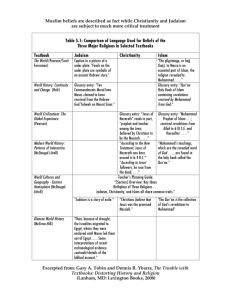

A Comparison and Contrast of Jesus and Muhammad Introduction

advertisement

A Comparison and Contrast of Jesus and Muhammad

Introduction

One of the key premises of the Quran is to respect God (Allah) and conform to the

words of His messenger, who Muslims believe to be the Prophet Muhammad. Quran

33:21: Indeed in the Messenger of Allâh you have a good example to follow for him who

hopes for (the Meeting with) Allâh and the Last Day, and remembers Allâh much. For

Muslims, The Prophet Muhammad is the last prophet of Allah and the paradigmatic

figure of the Islamic faith. For this reason the studying of the life and actions of

Muhammad is a quintessential component of Muslim life. However, like the search for

the Historical Jesus, it is very difficult for Islamic scholars to completely isolate

Muhammad from the array of cultural myths, miracles, and presuppositions that surround

him as a religious figure. According to Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah:

Behind the legendary Muhammad there lies one of the great figures of history, and,

although very little is known about his early years – the first certain date being that of the

migration from Mecca to Medina, which took place in AD 622 – it is possible to build up

the events of his real, as distinct from his symbolic life. 1

The most primitive of written information about the life of the Prophet Muhammad are

found within the Qur’an. However, other than the incidental allusions to and hidden data

about his life, the Qur’an itself gives very little detailed information about the behavior

and life of Muhammad. Within this paper I will compare and contrast the stories of

Muhammad and Jesus by examining the writings of the New Testament Gospels, Fred

Donner, and the English translations of the oldest surviving biographies of the Prophet

that were written by Ibn Ishaq. The paper will survey differing interpretations,

perspectives, and reoccurring themes in both Muhammad and Jesus’ personal, cultural,

and historical narratives while taking into account the hearsay that surrounds them.

The Basic Narratives of the Prophet Muhammad and Jesus

The earliest surviving biography of the Prophet Muhammad is a two-part recession

written by Ibn Ishaq. Ishaq was a devote Muslim who lived from 704-767 AD. Although

the biography no longer exists in its original form, it is respected as one of the closets

depictions of the prophet because it was written just one hundred and twenty to one

hundred and thirty years after the death of the Prophet. Ibn Ishaq used a collection of

written oral traditions and anecdotes to form Muhammad’s first biography, which is

usually called the Sirat Rasul Allah ("Life of God's Messenger").

Before we directly confront the actual prophetic narrative, I want to discuss the

methodology of Ibn Ishaq’s writing. Ibn Ishaq is known for his chronological

arrangement of Muhammad’s life that centers on the periods prior to, during, and after

the Prophet’s revelation. He writes with a sense of Islamic superiority, especially when it

comes to describing Muhammad’s call that was greatly influenced by Judaism and

Christianity.

It is also valuable to note that Ibn Hisham has heavily edited the current editions

that we have of Ibn Ishaq’s biography of Muhammad. Hisham chose to omit the writings

1Ibn

Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah; translated by Michael Edwards, The Life of Muhammad (London,

1964), pp. 32

Comment [JB1]: Iwasgladthat

thisclassallowedyoutofinally

makethecomparisonyouhad

wantedtodobasedonsome

earlierstudiesandclasses.

Comment [JB2]: Butasyounote,

nottheonlyone.

Comment [JB3]: Thisofcourse

comesmuchlaterwiththehadith

literature.

Comment [JB4]: AsIoftenwrite,

Isometimesdon’twantalotof

commentsonthosesectionofa

paperthataregoodsummariesof

historicalorhermeneutical

questionwhenIthinktheyare

welldone,astheyarehere.

Comment [JB5]: Justasthe

ChristiandidfortheJewsandthe

Baha’ishavedoneinturnfor

Islam.

in the original biography that were not supported by the Qur’an. However, within these

narrative changes there exists a large quantity of contradictions that neither Ibn Ishaq’s

nor Ibn Hisham sought to reconcile. The composers/editors are apparently not bothered

by their contradictions. For instance, Ibn Ishaq writes about the conversion of Umar Ibn

al-Khattad in two different accounts one right after the other. The two stories are

mutually exclusive and Ibn Ishaq does not even comment on their blatant contradictions

towards each other. 2 In many ways these contradictions are also rooted in the Ibn Ishaq’s

need to mystify the prophetic figure. Fred Donner, an Islamic scholar and Professor of

Near Eastern History at the University of Chicago, responds to the contradictions in Ibn

Ishaq miracle writings with the following statement:

The vast ocean of traditional accounts from which the preceding brief sketch of

Muhammad’s life is distilled contains so many contradictions and so much dubious

storytelling that many historians have become reluctant to accept any of it at face value.

There are for example, an abundance of miracle stories and other reports that seem

obviously to belong to the realm of legend, such as an episode similar to the “feeding the

multitudes” story in Christian legends about Jesus. The chronology of this traditional

material about Muhammad, moreover, is not only vague and confused, but also bears

telltale signs of having been shaped by a concern for numerological symbolism. 3

In Ibn Ishaq’s writings, the stories of the Muhammad figure are arranged and

written in an apologetic form because it proves that He was the greatest and last of God’s

prophets. His writing validate the Prophet’s divine nature with his supernatural

abilities/miracles and even his mother’s prenatal experiences. Ibn Ishaq’s version of the

Muhammad biography portrays the prophet in a variety of ways. For instance, (1) he is

depicted as a man of honesty because of his strategy towards the rebuilding of the

Ka’bah; (2) there are several accounts that portray him as a warrior i.e. the Battles of

Badr and Uhud; (3) and finally, but most importantly, he is portrayed as a prophet whose

prophetic career begins at the age of forty. 4 This is the where Donner’s and Ibn Ishaq’s

portrayals of the prophet Muhammad differ greatly. Donner’s account is a “very

condensed summary of the traditional biography of Muhammad, setting aside those

reports that are clearly legendary”. 5 For Donner, the main issue with the Ibn Ishaq’s text

is that it is a mystified account of the prophet’s personal narrative that was not written

during his actual era but centuries later. 6

Although one would like to think that Ibn Ishaq’s account is without controversy

because of its time-honored historic value, there are those who challenge its depictions.

For instance, while the Qur’an itself seems to reject the need to prove such a claim, i.e.

Q2: 23; 29: 50, it is believed that Ibn Ishaq may have written his works during a time

2Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 51.

3Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 51.

4Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah; translated by Michael Edwards, The Life of Muhammad (London, 1964),

pp. 18.

5

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 39.

6

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 50.

Comment [JB6]: Aconsistent

featureofIslamicscholarship:the

Qur’analwayscomesfistand

foremost.

Comment [JB7]: MyMuslim

friendsalwaystherealmiracleof

Islamistherevelationofthe

Qur’anitself.

Comment [JB8]: Thebattlesover

thehadithliteraturehasgoneon

forthewholehistoryofIslamic

scholarship.

when Christian criticisms of Muhammad was at an all-time high. Many original texts

about Muhammad “offer miracle stories or improbable idealizations and seem to belong

to the realm of legend or religious apologetic”. 7 This is just one way of viewing Ibn

Ishaq’s writings, but it is not intended to devalue its sacredness to Muslim believers. In

the words of Michael Edwards:

The miraculous is always present and is given the same weight as mundane descriptions

of the prophet’s actions. Because tales of miracles may be unacceptable today, this does

not mean that other parts of the biography are untrustworthy. The facts are there, and the

miraculous is that essential embroidery of faith, which the life of no religious leader –

from Christ to the Buddha – is without. 8

This mystification of the prophet continues throughout the Ibn Ishaq narrative. It

can particularly be seen in his version of Muhammad’s birth. Parallel to the Matthew

narratives of Jesus, and many other messianic narratives of that age, the mother of

Muhammad became aware of her pregnancy by way of a vision. During this supernatural

experience, a declaration was made to her by a divine being saying, “Thou art pregnant

with the prince of this nation. When he is born on this earth, thou must say, ‘I place him

under the protection of the only One, from the wickedness of every envious person.’ And

thou must name him Muhammad.” 9 On the night that Muhammad was born, a Jew

standing on a roof said: “This night the star has risen, under which the apostle is born.” 10

After which, Muhammad’s mother sends out words, to his father, that: “An infant is born

to you; come and see him.” 11 A large portion of Muhammad’s narrative is similar to that

of the birth narrative of Jesus. For instance, like the narrative of Muhammad, in Luke and

Mathew Mary is told of her pregnancy by an angelic figure. According to Matthew 1:21

the angel said “and you shall call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their

sins.” Additionally, there was a host of angels appearing to shepherds and the star of

Bethlehem guiding them bringing gifts to Mary and the infant Christ. It could be argued

that the parts of Muhammad narrative that are likened unto the story of Jesus are strategic

efforts made by Ibn Ishaq to mystify the prophet. If such a hypothesis were true, such

would have intentionally intercepted an idea of divineness into the minds of Islamic

believers who were reading the sacred texts to learn about the Prophet.

According to Ibn Ishaq’s account, these miraculous experiences continued

throughout Muhammad’s childhood. According to one particular story, Muhammad and

his brother were tending to their father’s sheep behind their tents when the young prophet

fainted. His brother ran for help saying that something was wrong with Muhammad.

When Muhammad’s mother asked what was wrong, Muhammad, “standing up with a

livid face” said, “Two men in white raiment came and threw me down and opened my

7

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 39.

8

Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah; translated by Michael Edwards, The Life of Muhammad (London, 1964),

pp. 12.

9

Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah; translated by Michael Edwards, The Life of Muhammad (London, 1964),

pp. 17.

10

Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah; translated by Michael Edwards, The Life of Muhammad (London, 1964),

pp. 17.

11

Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah; translated by Michael Edwards, The Life of Muhammad (London, 1964),

pp. 18.

Comment [JB9]: True;just

becauseweliveinatimeand

culturethatdoesnottreasure

miracles,thishasnotalwaysbeen

thecase.

Comment [JB10]: Makessense

tome,butthenIammodern

scholarswhobelievesthattexts

arealwayspartoftheirhistorical

context.

belly and searched therein for I know not what.” His father said, “I’m afraid that this

child has had a stroke.” Muhammad’s mother asked her other son if he feared that a

demon had possessed Muhammad and he answered yes. Muhammad’s mother replied

“no demon had any power over her son who had a great future before him” 12 Similarly,

there are also narratives, like those of Ibn Ishaq’s accounts of the experiences of

Muhammad’s childhood, where Jesus’ childhood is also accounted for.

One of the ideas that both Ibn Ishaq and Fred Donner seem to agree with is the

notion that Muhammad’s religious ideology was likely influenced by Meccan culture.

“Mecca was a town whose inhabitants were heavily involved in two activities: commerce

and religion”. 13 It is thought that Muhammad was probably a merchant of some sort. He

managed his wife’s “caravan trading ventures”. 14 The tribe of Quraysh organized various

trading fairs, which made Muhammad’s surroundings a sort of religious melting pot. In

addition to organizing these fairs:

The Quraysh tribe’s role as stewards of Mecca’s religious rituals, centered on the Ka’ba

and other holy sites around Mecca, also gave them contacts with many groups who came

to the Ka’ba to do their devotions there, particularly by performing ritual

circumambulations in the open area surrounding it. 15

Like, Ibn Ishaq’s writings that attempt to mystify the Muhammad figure in an

apologetical form, some scholars believe that the writers and composers of the New

Testament likewise mystified the messianic figure Jesus for the same reasons. For the

sake of brevity in proving this point I would like to centralize my examination of Jesus on

the Gospel according to Matthew. Matthew is a unique gospel account because it seeks to

establish, as its premise, the claim that in Jesus Christ, God dwells among the people and

eventually the New Testament Church. These claims can be seen in passages like: 1.23;

16.16 and 28.20. According to the Oxford Annotated Bible, “The purpose of its message

is to summon the reader or hearer to perceive that God is uniquely present in Jesus and to

become Jesus' disciple”. 16 The premise of proving that Jesus was in fact the unique

presence of God on earth begins with the genealogical connection that traces the line of

Abraham, the symbolic father of Israel, down to Jesus himself. Throughout its chapters,

the gospel of Matthew spends a great deal of time on the teachings of Jesus. Matthew

often expands the Markan miracle stories. 17 The other feature that contrasts Matthew's

style to that of Mark’s is that his commentary is more precise in its rabbinic quality than

12

Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah; translated by Michael Edwards, The Life of Muhammad (London, 1964),

pp. 20.

13

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 40.

14

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 40.

15

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 40.

16

Jack Dean Kingsbury "Matthew, The Gospel According to” The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Bruce

M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, eds. Oxford University Press Inc. 1993. Oxford Reference Online.

Oxford University Press. Harvard University Library. 1 May

2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t120.e0470

17

Wansbrough, Henry . "The Four Gospels in Synopsis." In The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford

Biblical Studies Online. 01-May-2011. <http://www.oxfordbiblicalstudies.com/article/book/obso9780198755005/obso-9780198755005-div1-402>.

Comment [JB11]: Andhedid

marryawomanwhowasa

merchant.

Comment [JB12]: Abetterchoice

thanJohn—justtryingalittle

humorthere.Math.‘sgospeldoes

havealotofthismaterialtosay

theleast.

many of the other gospels. 18 It was written for a community of Christian-Jews like those

at Antioch.

According to Mark Powell, the Robert and Phyllis Leatherman Professor of New

Testament at Trinity Lutheran Seminary in Columbus, Ohio, “Matthew’s implied readers

are expected to regard whatever the narrator says as reliable”. 19 Powell substantiates his

claim with the argument that by Matthew telling the account of Jesus’ birth, the reader is

suppose to believe that “Joseph is indeed a righteous man as the text says that he is”. 20

The technique that Matthew uses to recount the birth narrative would suggest and cause

the reader to believe, just as Ibn Ishap‘s writings would about Muhammad, that Jesus was

indeed the unique presence of God. “Matthew's Christology is theocentric, presenting

God's rule as manifest in the life of Jesus as an alternative to the sovereignty and power

of this-worldly rulers”. 21 Matthew also believed that Jesus was the fulfillment of Jewish

scripture and that he was the foretold messianic figure. According to the Oxford Bible

Commentary:

Matthew sees the message of Jesus as bringing the teaching of Judaism to completion.

Thus on twelve occasions he shows Jesus acting ‘in order to fulfill’ the scripture (1:23;

2:6; 15, 18, 23; 4:15–16; 8:17; 12:18–21; 13:35; 21:5; 26:56; 27:9–10 ) as though with no

other motive for action. He sees the miracles of Jesus as the fulfillment of Isa 61 (Mt

8:17; 11:5–6) and the resurrection of Jesus as the sign of Jonah (Mt 12:39; 16:4 , whereas

Mk 8:12 misses this significance, saying that no sign will be given). He sees Jesus as the

new Moses, reflecting Moses' career in his infancy (this is the chief theme of Mt 2), in his

lawgiving (Mt 5:1), and in his final charge on the mountain (Mt 28:16 ). Consequentially,

the people of Jesus form the new Israel, replacing the old. In Mt 16:18 ‘my church’ (or

more exactly ‘my community/congregation’) mirrors the people whom God called to

himself in the desert, and they are the nation to which the kingdom will be given when it

is taken away from the unresponsive tenants (22:43). The repeated promise of his

presence among them (1:18; 18:20; 28:20) corresponds to the presence of God among the

people of Israel. 22

The excessive apologetic discourse used by Matthew to demonstrate and validate the

divinity of Jesus was important because “Scholarly opinion holds that the church for

which Matthew was written was made up of Christians of both Jewish and gentile

origin”. 23 The message and story of Jesus needed defending because the church, which

18

Wansbrough, Henry. "The Four Gospels in Synopsis." In The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford Biblical

Studies Online. 01-May-2011. <http://www.oxfordbiblicalstudies.com/article/book/obso9780198755005/obso-9780198755005-div1-402>.

19

Powell, Mark A. Chasing the Eastern Star: Adventures in Biblical Reader-Response Criticism,

Louisville: Westminster John Knox 2001.

20

Powell, Mark A. Chasing the Eastern Star: Adventures in Biblical Reader-Response Criticism,

Louisville: Westminster John Knox 2001.

21Boring, M. Eugene. "Matthew's Narrative Christology: Three Stories." Interpretation (Richmond, Va.)

64.4 (2010): 356-367. Humanities Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

22

Wansbrough, Henry. "The Four Gospels in Synopsis." In The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford Biblical

Studies Online. 01-May-2011. <http://www.oxfordbiblicalstudies.com/article/book/obso9780198755005/obso-9780198755005-div1-402>.

23

Jack Dean Kingsbury "Matthew, The Gospel According to” The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Bruce

M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, eds. Oxford University Press Inc. 1993. Oxford Reference Online.

Oxford University Press. Harvard University Library. 1 May

would have been the primary readers of Matthew, were living in extremely hostile

environments that were full of religious and social tension. 24 The imagery that Matthew

uses to describe Jesus not only validates the purpose of Matthew’s writings about Jesus,

but it also validates the actions of Jesus. Matthew's Christology promotes its premise by

utilizing a plurality of titles that have “an obvious focus on royal titles: Christ, king, and

son of David are dearly in this category, and both Son of God and Son of Man have royal

overtones elaborated in Matthew's narrative.” 25 This proves that Jesus was indeed

mystified by writers and composers of the New Testament just as Muhammad was by the

writings of Ibn Ishaq.

One of the advantages to the Muhammad narratives is that they give a great deal of

information about how the Prophet developed into a great thinker. This is one of the

disadvantages of the Christ narrative in the Bible. Other than the fact that he was a Jew

and visited the synagogue once when he was twelve, the Bible give very little insight on

where and what Jesus learned or his affiliations that could have influenced his

viewpoints. Even in the story about Jesus’ visit to the temple as a boy the reader is not

afforded the opportunity to see Jesus learning but rather we only see him teaching.

According to Donner, Muhammad entered into the commercial and cultic life of Mecca at

an early age. After marrying a wealthy and older widow, Khadija, he gained great respect

amongst his Quraysh associates. Unlike many of the other merchants of his time,

Muhammad did not spend the majority of his time trading with the Jews, Christians, or

other traders passing though the community. Instead, he saw being a merchant as a

chance for him to listen and learn from the religious traditions of others. Muhammad

would spend hours contemplating and comparing the religious views of others against his

own tradition. Because of his level of respect for religious diversity, even at that stage in

his life he was revered and most known for his unusual level of astuteness and rectitude.

Muhammad was extremely spiritual and clear about his understanding of moral authority.

“He also began to feel a periodic need for meditation and took to secluding himself now

and then in order to contemplate his life”. 26 Because of the influence that the Jews and

Christians had on him coupled with his experiences with Arabian ancestral polytheism,

Muhammad started having strange dreams and bright visions. One of the visions caused

him to dedicate his life to the work of Allah. According to Ibn Ishaq:

One day, Muhammad said that while he was sleeping, Gabriel came to him with

something that had writing on it, and said, “Read!” According to Muhammad, “I said,

‘What shall I read?’ He pressed me with it so tightly that I thought it was death; then he

let me go and said, ‘Read!’ I said, ‘What shall I read?’ He pressed me with it again so

that I thought it was death; then he let me go and said ‘Read!’ I said, ‘what shall I read?”

He pressed me with it the third time so that I thought it was death and said, “Read!’ I

said, ‘what then shall I read? —And this I said only to deliver myself from him, lest he

would do the same to me again. He said, “Read in the name of thy Lord who created,

who created man of blood coagulated. Read! Thy Lord is most beneficent, who taught by

24

Jack Dean Kingsbury "Matthew, The Gospel According to” The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Bruce

M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, eds. Oxford University Press Inc. 1993. Oxford Reference Online.

Oxford University Press. Harvard University Library. 1 May

25

Boring, M. Eugene. "Matthew's Narrative Christology: Three Stories." Interpretation (Richmond, Va.)

64.4 (2010): 356-367. Humanities Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

26

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 40.

Comment [JB13]: Again,good

summariesofimportantdatafor

yourargumentandalsoaboutthe

hostileenvironmentthatprobably

causetheauthor/stousethiskind

ofnarrative.

Comment [JB14]: Likethe

BuddhaandConfuciushedidlivea

lotlongerthanJesus.Thishelps

suchnarrativesalot.

Comment [JB15]: Agoodpoint

thatIhadnotreallythoughtabout

butshould.

the pen, Taught that which they knew not unto men.’ So I read it and he departed from

me. And I awoke from my sleep, and it was as though these words were written on my

heart...When I was midway on the mountain, I heard a voice from heaven saying, "O

Muhammad! Thou are the apostle of God and I am Gabriel." I raised my head towards

heaven to see, and lo, Gabriel in the form of a man with feet astride the horizon, saying,

"O Muhammad! Thou art the apostle of God and I am Gabriel." I stood gazing at him,

moving neither forward or backward; then I began to turn my face away from him, but

towards whatever region of the sky I looked, I saw him as before. 27

After this experience with Gabriel, Muhammad’s theology changed significantly. He

“began to preach publicly the message that was being revealed to him: the oneness of

God, the reality of the Last Judgment, and the need for pious and God-fearing

behavior”. 28 His earliest followers were his relatives, wife, and people from theologically

feeble clans of Quraysh and “marginal social groups”. 29

When the apostle began to spread Islam among his people as Allah had commanded him,

they did not gainsay him until he began to abuse their idols; but when he had done this,

they accused him of seeking power, denied his revelation, and united to injure him.

...Several nobles of the Quraysh, including Utba and Abu Sufyan, went to Abu Talib and

said, 'your nephew has insulted our gods and condemned our religion. He considers our

young men to be fools, and our fathers to have erred. You must either restrain him or

allow us free action against him, since your religion is the same as ours, opposed to his.'

But the apostle continued to preach the religion of Allah and to seek conversions, and

the people hated him. 30

This spiritual experience takes place while he is meditating in a cave in the month of

Ramadan. Ibn says: “Every year the Apostle of Allah spent a month praying at Hira and

fed the poor who came to him; and when he returned to Mecca he walked round the Kaba

seven or more times, as it pleased Allah, before entering his own house”. 31 Ibn uses this

story to convey the message that Muhammad was called to preach/prophesy to the

citizens of Mecca, about being prepared for the Day of Judgment.

HEALINGS

Unlike Jesus, it is uncertain as to whether or not the Prophet Muhammad actually

performed healings and miracles. Muslims accept the idea of Jesus performing miracles

as a given fact because it is supported by the Qur’an. However, Muslims tend to disagree

on whether Muhammad performed miracles or not. The central conflict around this

subject matter has to do with the contradictions between the Qur’an and the hadith. The

hadith are the recorded teachings and actions of Muhammad and the Qur’an is

27

Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah; translated by Michael Edwards, The Life of Muhammad (London, 1964),

pp. 36.

28

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 41.

29

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 41.

30Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah; translated by Michael Edwards, The Life of Muhammad (London,

1964), pp. 18.

31Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah; translated by Michael Edwards, The Life of Muhammad (London,

1964), pp. 36.

Comment [JB16]: Againthereis

aparalleltoearlyChristianhistory

aswell.

Comment [JB17]: Inotedthis

above.

Muhammad’s documentation of the revelations that he had with the angel Gabriel. Thus,

since Muhammad did not have control over hadith it opens up his personal narrative for

his followers to contribute different dynamics that may or may not have been true. This

situation is quite similar to the quest for the historical Jesus. For the sake of brevity we

will not be able to examine all of Jesus’s accounts of healing and miracles but I have

included a brief overview in the form of a list.

• A man who was deaf and unable to talk (Mark 7:31-37 NRSV)

• A man with a shriveled hand (Matthew 12:9-13; Mark 3: 1-6; Luke 6:6-11 NRSV)

• A man with dropsy (or edema) (Luke 14:1-6 NRSV)

• A woman who was bent over and crippled (Luke 13:10-17 NRSV)

• An official's son who was dying (John 4:48-52 NRSV)

• Blind men (Matthew 9:32-34; 20:29-34; Mark 8:22-25; 10:46-52; John 9:1-38;

18:35-43)

• Calming the storm as he and the disciples crossed a lake (Matthew 8:23-27; Mark

4:35-41; Luke 8:22-25)

• Causing a fig tree to wither (Matthew 21:18-22; Mark 11: 20-25)

• Feeding crowds with small amounts of food (Matthew 14:13-21; 15:32-38; Mark

6:34-44; 8:1-9; Luke 9: 12-17; John 6:1-15)

• Fever of Peter's mother-in-law (Matt. 8:14-15; Mark 1: 29-3 1; Luke 4:38-39

NRSV)

• Finding money for taxes in the mouth of a fish (Matthew 17:24-28)

• Invalid at the Pool of Bethesda (John 5:1-15 NRSV)

• Large catches of fish (Luke 5:1-11; John 21:1-14)

• Men with leprosy (This disfiguring skin disease was often fatal.) (Matthew 8:1-4;

Mark 1:40-45; Luke 5: 12-19; 17:11-19)

• Paralyzed man (Matthew 9:1-8; Mark 2:1-12; Luke 5:18-26)

• Raised a ruler's daughter from the dead (Matthew 9: 18-26; Mark 5:21-43; Luke

8:40-56)

• Raised his friend Lazarus from the dead out of his grave (John 11:1-44 NRSV)

• Raised widow's son from the dead (Luke 7:11-17 NRSV)

• Restored the ear of the high priest's servant after Peter struck him with a sword

(Luke 22:49-51 NRSV)

• Roman army officer's sick servant (Matthew 8:5-13; Luke 7:2-10)

• Turning water into wine at a wedding (John 2:1-11)

• Walking on water during a storm (Matthew 14:22-33; Mark 6:45-52; John 6:16-21)

• Woman with menstrual problem (Matthew 9:20-22; Mark 5:24-34; Luke 8:43-48)

Unlike Muhammad, Jesus never wrote or documented anything about himself or his

ministry. The mystery around the life events of the two religious figures are similar

because there is also a great deal of concern in the academic study of the New Testament

pertaining to how much of the gospels are myth verses historical accounts. “In current

historical Jesus scholarship, an especially sharp divide centers on two issues: how best to

categorize the core of Jesus' speech, and how to understand the essential nature of the

narrative Gospels and what one can reasonably take as reliable historical reportage in

Comment [JB18]: Oneofthe

problemsforallthegreatreligious

leadersofanyage.Iknowthatthe

DaliLamaisalwaysamusedwhen

hehearsstoriesabouthisgreat

powers.OnceIheardhimsaythat

hehadenoughtrouble

rememberingwhathehadfor

breakfastmuchlesswhatwenton

inhispreviouslives.

Comment [JB19]: Againusefulto

remindusoftheimportantof

miraclesfortheChristian

narrative.

them.” 32 One of the more popular questions in the field is concerning the messianic

identity of Jesus. Most critical twentieth century scholarship will contend that Jesus did

not claim to be the Messiah. According to Michael F. Bird, lecturer in theological studies

at Bible College of Queensland in Toowong, Australia, Jesus did not use the title of

Messiah to describe himself. 33 This is an example of how the writers of the accounts of

both Jesus and Muhammad could apply any title or idea that they wanted on to the

figures, whether it was true or not.

Arguably, the gospels often used the narratives of Jesus working miracles as a form

of apologetics. For example, in Matthew 11:2-5 Jesus says that he performed miracles for

the sole purpose of revealing to people that he was the Son of God.

1 Now when Jesus had finished instructing his twelve disciples, he went on from there to

teach and proclaim his message in their cities. 2 When John heard in prison what the

Messiah was doing, he sent word by his disciples 3 and said to him, "Are you the one who

is to come, or are we to wait for another?" 4 Jesus answered them, "Go and tell John

what you hear and see: 5 the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are

cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to

them. 6 And blessed is anyone who takes no offense at me." Matthew 11:2-5

Comment [JB20]: Whata

contestedfield.Oneofthereasons

IsometimeslikemyConfucian

studiesisthatwehavealotmore

earlyresourcescomparedtothe

Christiantexts.

Comment [JB21]: Walls,the

greatmissionscholar,hasargued

thatthetermChristwasfirstused

inAntiochtotranslatetheterm

MessiahintoGreekforthenon‐

Aramaicspeakersthere.

However, according to the Qur’an Muhammad, unlike Jesus, had no need to work

miracles to prove that he was indeed a prophet. According to Quran. Muhammad was to

tell people:

"The signs are only with Allah, and I am only a plain warner." Is it not sufficient for them

that We1 have sent down to you the Book (the Quran) which is recited to them?

SURAH 29:50-51

And if Allah touches you with harm, there is none who can remove it but He, and if He

intends any good for you, there is none who can repel His Favour which He causes it to

reach whomsoever of His slaves He wills.

SURAH 10:107

Muhammad: "Who then has any power at all (to intervene) on your behalf with Allah, if

He intends you hurt or intends you benefit?"

SURAH 48:11

Muhammad: I have no power over any harm or profit to myself except what Allah may

will.

SURAH 10:49 (SEE ALSO SURAH 7:188.)

In other words, the signs were for Allah to perform, not the prophet. Muhammad also

believed that the Quran was sign enough.

32

Carvalhaes, Claudio, and Paul Galbreath. "The Season Of Easter: Imaginative Figurings For The Body

Of Christ." Interpretation (Richmond, Va.) 65.1 (2011): 5-16. Humanities Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 6

Dec. 2011.

33Chilton, Bruce. "[Are You The One Who Is To Come? The Historical Jesus And The Messianic

Question]." Interpretation (Richmond, Va.) 65.3 (2011): 308-310. Humanities Full Text (H.W. Wilson).

Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

Comment [JB22]: Good

summary.

Muhammad rejects this notion of a prophet and affirms that a prophet is neither an angel,

nor does he have an angel dwelling in him. He is only a man, who speaks to men (Cf.

6:8-9). Muhammad is ordered by God to speak with no pretention and with no authority

of his own. He emphatically states that he, himself, has no "knowledge of the un- seen"

(7:188), nor is he an angel (6:50). In the Qur’an the Quraish appear to be desperate for

"signs" (2:118; 3:183): "if only a por- tent were sent down upon him from his Lord!"

(10:21; 6:37; 13:27). In the demand for a "portent" God confirms to Muhammad that he

is not getting any; "Thou art a warner only, and for every folk a guide" (13:7). 34

For this reason, many Muslim scholars contend that Muhammad’s followers invented the

miracle stories in the Hadith after the prophet’s death to validate Muhammad’s prophetic

nature. As stated above this is also a suspicion in Christian scholarship. However, this

particular statement of Muhammad in Surah 29:50-51, is one example of how the

Muhammad and Christ figures somewhat differ. Although there are accounts in the

gospels where Jesus put more of the focus on God rather than himself; i.e. Mark 10:18

And Jesus said to him, "Why do you call Me good? No one is good except God alone;

Jesus is depicted in the scriptures as possessing supernatural powers.

One of the earliest authorities of hadith Ibn Sa'd (764-845) wrote a book entitled,

Kitäb at- Tabaqat (Book of Classes). 35 The legendary book is revered as a basic source

of narratives on the life of the Prophet Muhammad, his wives, and his children. 36

According to Abu Qurra, “The section of his work that is devoted to the miracles of

Muhammad……….sound as if they are being offered as responses to such Christians as

and they bear an amazing resemblance to miracles of Jesus found in the Gospels”. 37

Below I have listed Abu Qurra’s selective list of characteristically equivalent themes 38 :

Muhammad's command causes trees to be uprooted after then returned to their

place. [Cf. Lk. 17:6]

Muhammad ascends into heaven sitting on a branch of a tree with Gabriel sitting on

another. [Cf. Lk. 24:50-51 and Mt. 4:6]

Muhammad is protected from his enemies. [Cf. Lk. 20:19; Jn. 7:20- 46, esp. 7:30]

Muhammad turns water into milk and fresh goat cheese. [Cf. Jn. 2:1 -11]

A wolf addresses a shepherd and bids him to go where the Prophet is preaching.

[Cf. Jn. 1:43 -49?

34"The

Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

35The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

36The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

37The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.The

anti-Islamic works of Abu Qurra are in the form of dialogues between a Christian and a Muslim. We must

assume that in these dialogues the interlocutors are fictitious characters. However such dialogues, which

were written as easy manuals for the sake of Christians, reflect real circumstances, and imply actual

confrontations. 38Ref.tothetextinA.GuillaumeAReaderonIslam,pp.309-30.For reasons of a better accounting I have

numbered each miracle as it begins with a new isnâd, or chain of transmitters.

Comment [JB23]: Thisisoneof

thosestatementsthatmakemany

scholarsthinkthataveryJewish

notionofJesusmakessenseand

notthefullblownTrinitarian

theoriesthatwinoutmuchlater.

OnlyGodisgreat;whichis

somethingaMuslimwouldagree

withdoubtlessly.

Comment [JB24]: Notlikingfist

thatmuch,Ipreferthisversion

withthegoatcheese,whichIdo

love.

Muhammad raises his gaze to the sky and then to the ground while exhorting his

listeners against sensuality. [Cf. Jn. 8:1 -11]

Muhammad reveals to his Jewish challengers four hidden matters. [Cf. Jn. 4:4-19]

Muhammad reveals the names of those 'hypocrites' who had been speaking against

him. [Cf. Lk. 13:10-17 and Mt. 9:3 -4]

Muhammad causes water or food to multiply, wherefrom many people either

perform ablutions or feed themselves. [Cf. Mt. 14:13-21; Mk. 6: 32-44; Lk. 9:1017; Jn. 6:1-13]

Muhammad heals a man with a bad eye. [Cf. Mk. 8:22-26 and else- where]

Muhammad causes a tree branch to become a steel sword. [Cf. Lk. 22:35-38?]

Muhammad foretells the destruction of prejudicial documents of the Quraish

against the Banu Hashim. [Mark 13:1-4}

In a text addressed to his Muslim interlocutor 39 , Abu Qurra also claims:

My father has taught me to accept a messenger (only) if he has been fore- told by a

previous one, and if he has proven himself reliable through signs. Your Muhammad,

however, is completely deprived of and irrelevant to both. For neither an old prophet preannounced him as a prophet, nor did he prove himself reliable through sign. 40

Another persuasive writing on the subject matter of miracles as it pertains to Jesus

and Muhammad is the letter "Emir at Damascus " which is attributed to Arethas,

Archbishop of Caesaria (850-early tenth century). In the portion of his letter that

compares Jesus, in terms of miracles to Muhammad, he says:

We Christians were informed from many prophets who pre-announced the presence on

earth of Christ, the Son of God and God, and we learned of him and believed in him

through the deeds this same Jesus Christ did on earth. For, everything that the

prophets...pre-announced about Christ was accomplished by him, that he will be born of a

virgin and that he will perform many miracles on earth, he will raise men from the dead,

will expel demons from men, and will heal sick men, and that he will be crucified by the

lawless Jews. 41

39T

The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.PG he

anti-Islamic works of Abu Qurra are in the form of dialogues between a Christian and a Muslim. We must

assume that in these dialogues the interlocutors are fictitious characters. However such dialogues, which

were written as easy manuals for the sake of Christians, reflect real circumstances, and imply actual

confrontations.

40The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.PG

97:1544CD. Progressively Byzantine writers challenged the prophethood of Muhammad on the basis of

five criteria, not necessarily in that order: testimonies of revelation, testimonies of previous prophets,

proofs of prophetic ability, proof of miracles, and examination of his personal character. Cf. A. Th. Khoury,

La Controverse byzantine avec l'Islam (VIIe Cahier d'Etudes Chrétiennes orientales, Foi et Vie (Paris,

1969), pp. 38-40. The his- tory of the Muslim-Christian dialogue shows a systematic response on the part

of the Muslims to each one of these challenges and a reversion of the Christian criticism. It seems to me,

however, that this exercise resulted in the gradual exaltation of Muhammad and contributed to a change in

the religion from Islam to Mohammedanism.

41

P. Karlin-Hayter, "Arethas' letter to the Emir at Damascus," Byzantion, 29-30 (1979-60), 293.

I want to briefly recount a few of the accounts of healings on both characters. The

first documented healing of Muhammad began with a vision. The Angel Gabriel came to

the Prophet Muhammad in a dream and told him that the Quraysh was devising a plot to

stab him while he was sleeping. On the night of the assassination, Muhammad ordered

for his cousin `Ali ibn Abi Talib to sleep in his bed while Muhammad and Abu Bakr hid

in a cave for three days. While in the cave many historians claim that Abu Bakr was

bitten by a poisonous snake and began to suffer intensely. Supposedly Muhammad said,

"Don't be sad, Abu Bakr, because Allah is with us." And then Abu Bakr miraculously

recovered. This healing narrative is quite similar to the spoken healing of the lame man at

the pool of Bethzatha in the Biblical story of St. John chapter five.

After this there was a festival of the Jews, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. 2Now in

Jerusalem by the Sheep Gate there is a pool, called in Hebrew Beth-zatha, which has five

porticoes. 3In these lay many invalids—blind, lame, and paralyzed. 5One man was there

who had been ill for thirty-eight years. 6When Jesus saw him lying there and knew that he

had been there a long time, he said to him, “Do you want to be made well?” 7The sick

man answered him, “Sir, I have no one to put me into the pool when the water is stirred

up; and while I am making my way, someone else steps down ahead of me.” 8Jesus said

to him, “Stand up, take your mat and walk.” 9At once the man was made well, and he

took up his mat and began to walk. Now that day was a Sabbath. 10So the Jews said to the

man who had been cured, “It is the Sabbath; it is not lawful for you to carry your mat.”

11

But he answered them, “The man who made me well said to me, ‘Take up your mat and

walk.’” 12They asked him, “Who is the man who said to you, ‘Take it up and walk’?”

13

Now the man who had been healed did not know who it was, for Jesus had disappeared

in the crowd that was there. St. John 5

In both of these healing narratives the miracles take place because of words that Jesus or

Muhammad spoke. Muhammad said: "Don't be sad, Abu Bakr, because Allah is with us"

and Jesus said “Stand up, take your mat and walk.” Both instances claim that the sick

person was immediately healed. John’s biblical account says: “9At once the man was

made well, and he took up his mat and began to walk” and supposedly Abu Bakr

miraculously recovered. “In this narrative, reminding ourselves of the distinction made

by the Muslims between the words of the Qur’an and of the words of the Prophet, it is

Muhammad's own words that result in a miracle!” 42 Another more popular healing story

of Muhammad is about:

...The Apostles of Allah—upon whom be Allah's blessing and peace — was at al-Hajûn

and was in grief and distress. He said: 'Allahumma, show me this day a miracle, after

which I will not care who among my people treats me as false.9 Now there was a tree

ahead on the road leading to Madina, so he summoned it, and, separating itself from the

earth, it came till it was before him and salaamed to him. Then when he commanded it it

returned [to its place]. He said: 'After this I care not who among my people treats me

false. 43

42"The

Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

43Ibn Sa'd (764-845), Kitàb at-Tabaqàt al-Kabìr (Leiden, 1907), 1. The section of the Miracles has been

translated by A. Jeffery, ed., in his A Reader on Islam ('S-Gravenhage, 1962), p. 309. The entire book has

been translated into English by S.M. Haq and H.K. Ghazanfar (2 vols., Leiden, 1967-72).

According to Daniel J. Sahas, professor of Religious Studies at the University of

Waterloo

Following this one, there are two more similar miracles, in a rather amusing context.

Muhammad, out of modesty, orders two trees to join together in order to satisfy his

physical needs in private! Is this an effort on the part of the earliest Muslims, who might

have heard of those words of Jesus, to depict Muhammad as the true man of faith whom

Jesus was longing for, in vain, among his con- temporaries? Is this, perhaps, an effort to

show the fulfillment of Jesus' words in Muhammad, "the seal" of the Prophets? What

were the causes and the stimulus for the emergence of power and of the embellishment of

the life of Muhammad with miracles? 44

Comment [JB25]: Againavery

goodlistandcommentarythat

doesnotreallyneedmy

commentary.ButDanielSahaswas

andisagoodfriendofminefrom

mydaysinCanada.Hedidgreat

workinMuslim‐Christiandialog

andIamhappytoseeyourcitation

here.

However as I stated earlier, “Muhammad rejected such a notion and disavowed for

himself any such power.” 45 He believed that the message of the Quran itself (6:125) and

the Scripture (29:50) 46 to be the only sign that any prophet could possibly need to depict

themselves as a true man of faith. He also argued that

Not even the pronouncement of a Qur’an is able to cause an extraordinary event for the

unbeliever to believe: "Had it been possible for a Qur'än10 to cause the mountains to

move, or the earth to be torn asunder, or the dead to speak, (this Qur'än would have done

so)" (13:31). This statement seems to be in tension with Jesus' words "If you have faith as

a grain of mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, 'Move from here to there,' and it

will move; and nothing will be impossible to you" (Matt. 17:20), and "If you had faith as

a grain of mustard seed, you could say to this sycamore tree, 'Be rooted up, and be

planted in the sea,' and it will obey you" (Lk. 17:6). 47

The second healing story from the hadith is a recount that is supposedly narrated by

Muhammad's second wife Aisha 48 . According to her: “Muhammad used to pray for

healing for his wives and other sick Muslims, touching them with his right hand as he

prayed”. 49 However, Muhammad had two sons who died in their childhood, but there are

no records of him healing them. 50 Thus, since Aisha is the only person who ever told

about Muhammad’s house-call healings it is suspected that these stories are not true. 51

The casting out of demons

The gospels and the Quran talk about Muhammad and Jesus’s thoughts about

44The

Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

45"The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

46"The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

47"The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27 No 2-3 Sum-Fall 1982. Other Matter." Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 27.2-3 (1982): ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

48The Correct Books of Muslim, bk. 26, no. 5432.

49The Correct Books of Muslim, bk. 26, no. 5432.

50

The Correct Books of Bukhari, vol. 2, bk. 23, no.390. Narrated by Anas bin Malik.

51The Correct Books of Muslim, bk. 26, no. 5432.

Comment [JB26]: Therearea

numberofcaseswhereAisha’s

wordhasbeendoubtedinthe

Muslimworld.Ijustheardavery

goodpaperaboutthisbyamodern

Muslimwomanscholar.

demons. However, their teachings, reactions and relationships to demons were different.

For instance, Jesus casted out demons on several occasions but Muhammad did not. In

the Bible there are several stories of Jesus casting out demons. For instance: the man in

the synagogue which is found in Mark 1:23-28; Luke 4:33-37 NRSV; the daughter of a

Canaanite woman in Matthew 15:21-28; Mark 7:24-30 NRSV; the boy who suffered

from convulsions in Matthew 17:14-21; Mark 9:14-30; Luke 9:37-43; the mute man in

Matthew 9:32-34 NRSV and the blind and mute man in Matthew 12:22 NRSV. In order

to continue our comparison and contrast between Jesus and Muhammad we must put two

of their demoniac stories into dialogue with one another: Matthew 8:28-34 NRSV and

Ibn Kathir’s story as narrated by Ibn Abass.

28 When he came to the other side, to the country of the Gadarenes,* two demoniacs

coming out of the tombs met him. They were so fierce that no one could pass that way.

29

Suddenly they shouted, ‘What have you to do with us, Son of God? Have you come here

to torment us before the time?’ 30Now a large herd of swine was feeding at some distance

from them. 31The demons begged him, ‘If you cast us out, send us into the herd of swine.’

32

And he said to them, ‘Go!’ So they came out and entered the swine; and suddenly, the

whole herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake and perished in the water. 33The

swineherds ran off, and on going into the town, they told the whole story about what had

happened to the demoniacs. 34Then the whole town came out to meet Jesus; and when

they saw him, they begged him to leave their neighborhood. Matthew 8:28-34 NRSV

A Muslim woman came to him and told him, "These unclean ones---demons---possess me

and torment me and torture me." Muhammad said, "If you are patient in what you are

walking through, you will come in Resurrection Day before Allah clean from any sin, and

there will be no judgment against you. She said, "I swear in the name of the one who sent

you that I will have patience until I meet Allah, but I am afraid that this demon will come

and make me take my clothes off (in public)"[that I will be sinning]. Then Muhammad

told her, "Every time you feel the demon on you, you must go to Al-Ka'ba and wrap

yourself in the fabric that is draped over the Black Stone." Then Muhammad prayed for

her. 52

Let’s begin our exegesis of these texts with a consideration of their similarities. Within

both sacred texts the demoniacs are said to have approached the prophet to discuss their

condition. After which, the prophets then replied to them with instructions. It is important

to note that neither Jesus nor Muhammad touched the demoniac(s). In the Biblical

narrative, Jesus’ words heal the demoniac. However, in Ibn Kathir’s prose Muhammad

simply instructs the Muslim woman on how to live with her demons until Allah returns. It

is obvious that Jesus and Muhammad had different motives in their engagements with the

demoniacs. Furthermore, when Jesus addresses the demoniac he speaks to the demons

and not the individual, whereas Muhammad spoke to the Muslim woman not the demon

that she believed to be living in her. Lastly, Jesus’ instruction was for the demons to

leave the demoniac’s body while Muhammad’s instruction was for the woman to protect

her nakedness by going to Al-Ka'ba’s and wrapping herself in the fabric that was draped

over the Black Stone.

52Ibn

Kathir in Arabic, The Beginning and the End, vol 3, pt. 6, p. 154. Narrated by Ibn Abass.

Comment [JB27]: Nowthisisan

interestingparallelsetofstories.

Comment [JB28]: Interesting

pointactually.AgainMuhammadis

focusedontheperson’sownfaith

andnotwhatthedemonmightor

mightnotbeabletodo.

how The Era after muhammad’s death LIKENS The era of Jesus’ Death

Muhammad died in the hands of his wife Aisha and Jesus died on a Roman cross.

Unlike Muhammad, the followers who succeeded Jesus believed that God resurrected

him from the dead and that he had ascended to heaven with his physical body.

Nevertheless, despite the different types of deaths and beliefs about their present realities

and whereabouts, after the deaths of the prophet Muhammad and Jesus, their

communities of believers faced a great deal of challenges. For instance, Muhammad did

not appoint a successor because the era of the prophetic had ceased and Muhammad had

established himself as the last and greatest to hold the office. Muhammad’s followers

sought out on the difficult task of institutionalizing and continuing the disciplines and the

political system that he had established. They did such by establishing a state that

represented a sort of political unity. This initial governmental structure in Islam was

similar to what modern persons would refer to as constitutional. It consisted of a leader,

also known as a Caliph, officials that represented the people of the government, and a

system of laws and republic. Eventually the system of political governance became

known as a Caliphate in 632. 53 “The Caliphate (632-1258) has traditionally been divided

up into three periods: the ‘Rightly Guided Calips’ (632-661), the Umayyad empire (661750), and the Abbasid empire (750-1258)”. 54

The first Caliph in Islam was Muhammad’s father-in-law, Abu Bakr. Abu Bakr was one

of Muhammad’s companions and he was one of initial non-family converts to Islam. He

was also responsible for converting and introducing many people to the Islamic faith. In

many ways Abu Bakr was the ideal person to lead the new Islamic World because he was

not an old man and “he made the journey with Muhammad from Mecca to Medina at the

time of the Hijra and it had been Abu Bakr who led the prayers during the Prophet’s last

illness”. 55 After the reign of Abu Bakr, Umar ibn as Khattab, Uthman ibn Affan, and Ali

ibn Abi Talib served as Islamic Caliphs. Up until this point, the Caliphs were mostly

elected or selected on the wishes of their predecessor. However, after the first four

caliphs, also known as the Khulafah Rashidun, the Caliphate was claimed by dynasties

such as the Umayyads and the Abbasids. Caliphs were the protectors and defenders of the

faith charged with extending the rites of Islam. They believed, as was dictated in the

letter of al-Walid II, that:

The caliphs are the legatees of Prophets. From Abraham they have inherited every

treasury and every prophetic book, and they fight with the swords of prophethood, by

right of prophethood, above all, of course, the prophethood of Muhammad, whose

covenant they implement. But through Muhammad if now clearly invoked to legitimate

the caliphate, it is to God on the one hand and Utman on the other that the caliphs are

directly indebted for their authority. ‘The earth belongs to God, who has appointed His

khalifa to it’, as al-Farazdaq put it, echoing Mu’awiya. “God has garlanded you with

caliphate and guidance’, as Jarir said. The caliph is God’s trustee (amin Allah), God’s

governor, and a governor on behalf of truth. He is God’s chosen one, as several poets

state. But the reason why God chooses Umayyads rather than others is that the Umayyads

53Esposito,

J., ISLAM: THE STRAIGHT PATH, Oxford University Press, 4th edition, (1998) pg. 40

J., ISLAM: THE STRAIGHT PATH, Oxford University Press, 4th edition, (1998) pg. 40

55

Kennedy, Hugh. The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth

Century to the Eleventh Century. London: Longman, 1986.

54Esposito,

Comment [JB29]: Whichcausea

majorcivilwarandthetheological

splitinthecommunitythatwesee

playedouteventoday.

Comment [JB30]: Whichmakes

senseforalotoftribalsocieties

actually.TheMongolsdidmuch

thesamethingwhentheyfounded

theirempire.

are kinsmen of Uthman. 56

Their initial idea of the Caliph was that he was a deputy, trustee, and an imam of

guidance. They saw them as governors and they aggrandized the position of Caliph with

materialistic possessions. Many of their customs mirror what Catholic traditions

established as norm behavior in the presence of Popes. For instance:

The ruler’s exalted status was further reinforced by his magnificent palace, his retinue of

attendants, and the introduction of court etiquette appropriate for an emperor. Thus,

subjects were required to bow before the caliph, kiss the ground, a symbol of the caliph’s

absolute power. 57

After the death of Jesus, like the communities of Muhammad, the apostles of Jesus

were left to carry out the mission of Jesus and to establish doctrines, like hadiths, to

institutionalize Jesus’ movements. For this section of our discussion I would like to

reflect on the Lucian books of Acts. “The book of Acts is a survey of the history of the

early Church that covered about 30 years”. 58 Luke’s account in the book of Acts reveals

the structural and theological struggles of the early Christians and their relationships with

each other and the Gentiles. “Luke has a central motif that he illustrates through the

healing ministry of the early Church that is presented as being similar to that of Jesus. It

is to show the presence of Jesus despite his bodily absence.” 59 With in the book the

religious leaders use performed miracles and theological parallels to the words of Jesus

alleviate the tensions between the Jewish Christians and new converts who argue over

their obligations to Jewish law and how they found Gentile salvations to be questionable.

“Notwithstanding the value of the above, a foundational reason may be identifiable in the

rationale of Luke that meets with his overall aim of identifying the ministry of Jesus with

the ongoing ministry of the Church.” 60 Furthermore, there is a motif throughout the New

Testament that seeks to like certain religious leaders in the post-Christ movements and

establishment of the church that sought to liken certain persons to Jesus. For instance,

“There are a number of similarities between Jesus, Peter and Paul may be identified in

Acts and Luke”. 61 For instance: Lk.4.38, Acts 28.8;Lk.6.19, Acts5.15-16, 19.12. Peter

and Paul could be see as somewhat like the Caliphs that took over after the death of

Muhammad.

It could also be argued that Peter was appointed to be the head of the church by

Jesus himself. According to Matthew chapter sixteen Jesus said:

56Crone,

Patricia & Martin Hinds. God's Caliph: Religious Authority in the First Centuries of Islam.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. Pg 31

57Esposito, J., ISLAM: THE STRAIGHT PATH, Oxford University Press, 4th edition, (1998) pg. 55

58Warrington, K. "Acts And The Healing Narratives : Why?." Journal Of Pentecostal Theology 14.2

(2006): 189-217. New Testament Abstracts. Web. 8 Dec. 2011.

59Warrington, K. "Acts And The Healing Narratives : Why?." Journal Of Pentecostal Theology 14.2

(2006): 189-217. New Testament Abstracts. Web. 8 Dec. 2011.

60Warrington, K. "Acts And The Healing Narratives : Why?." Journal Of Pentecostal Theology 14.2

(2006): 189-217. New Testament Abstracts. Web. 8 Dec. 2011.

61Warrington, K. "Acts And The Healing Narratives : Why?." Journal Of Pentecostal Theology 14.2

(2006): 193. New Testament Abstracts. Web. 8 Dec. 2011. A.J. Mattill,'The Jesus- Paul Parallels and the

Purpose of Luke-Acts: H.H. Evans Reconsidered', Novum Testamentum 17 (1975), pp. 15-46 (28-29)

Comment [JB31]: Itdoescross

one’smind.

Comment [JB32]: Andtheswitch

fromMathewmakessensehere

becausewedogetLuke‐Acts;

whichisaboutmuch‘history’as

wegetinthegospels.Ihavecome

tolikeLukemuchbetteroverthe

lasttwodecades.Maybebecause

ofDanaRobert’sgreatworkin

missionhistory.

Comment [JB33]: Interesting

parallelIhadnotthoughtof

before;thisisonereasonIalways

enjoyreadingthisfinalpapers.

13 Now when Jesus came into the district of Caesarea Philippi, he asked his disciples,

"Who do people say that the Son of Man is?" 14 And they said, "Some say John the

Baptist, but others Elijah, and still others Jeremiah or one of the prophets." 15 He said to

them, "But who do you say that I am?" 16 Simon Peter answered, "You are the Messiah,

the Son of the living God." 17 And Jesus answered him, "Blessed are you, Simon son of

Jonah! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father in heaven. 18 And

I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades

will not prevail against it. 19 I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and

whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth

will be loosed in heaven." 20 Then he sternly ordered the disciples not to tell anyone that

he was the Messiah. 21 From that time on, Jesus began to show his disciples that he must

go to Jerusalem and undergo great suffering at the hands of the elders and chief priests

and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised. 22 And Peter took him aside

and began to rebuke him, saying, "God forbid it, Lord! This must never happen to you."

Matthew 16:13-22

In this passage of scripture Jesus is talking to his disciples about his death. He also

discussed with them the plan about the church and who would take over after his demise.

This is something that Muhammad never did which lead to a great deal of tension. For his

followers, the era of the prophetic had ceased because Muhammad had established

himself as the last and greatest to hold the office, thus it was even more difficult to

decipher who would be their new leader and what type of power they would have.

Similarly, the successor of the ministry of Jesus could not be seen as the Son of God as

was Jesus, but he did advise them about his eventual demise when he was alive.

Throughout the New Testament several equivalences may be drawn between the

ministries of Paul and Jesus" and between Peter and Jesus. 62 For instance, according to

A.J. Mattill 63 :

Jesus cast out demons

(Lk. 4.31-37), so did Paul

(Acts 16.16-18);

Both Jesus and Paul

cured fevers (Lk. 4.38; Acts

28.9)

Jesus heals a lame man

(Lk. 5.17- 26), so does Paul

(Acts 14.8-18);

Power

left

Jesus,

resulting in healings (Lk.

6.19), also Paul (Acts

19.11-12)

Jesus raised the dead (Lk.

7.11 -17), so did Paul (Acts

62M. Hengel, 'Between Jesus and Paul: The "Hellenists", the "Seven" and Stephen (Acts 6.1-15; 7.54-8.3)',

in M. Hengel (ed.). Between Jesus and Paul (Philadelphia: For- tress Press, 1983), pp. 1-29.

63

A.J. Mattill 'The Jesus- Paul Parallels and the Purpose of Luke-Acts: H.H. Evans Reconsidered', Novum

Testamentum 17 (1975), pp. 15-46 (28-29)

Comment [JB34]: Ihavealways

wonderedifMuhammadthought

hewouldrecoverformhisillness.

TheBuddhaalsodiedofillnessbut

knewhewoulddieandhence

spenttimeonorderingthesangha

forthetimeafterhisfinaldemise

inbodybutnotdharma.

20.7-12)

Touching Jesus' garment

achieved healing (Lk. 8.44),

also Paul (Acts 19.12).

Jesus (Lk. 19.45-48) and

Paul (Acts 21.26) enter the

temple on their entry into

Jerusalem

Both are seized by a mob

(Lk. 22.54, Acts 21.30)

Both are slapped by the

priest's

assistants

(Lk.

22.63-64, Acts 23.2)

Both are involved in four

trials (Lk. 22.26; 23.1, 8,13;

Acts 23; 24; 25; 26)

Both have a Herod

involved in their trials (Lk.

23.6-12; Acts 25.13-26.32)

Both have a centurion act

positively towards them

(Lk. 23.47; Acts 27.3, 43)

Both of their ministries

conclude in the context of

the fulfillment of Scripture

(Lk. 24; Acts 28)

The parallels between the two figures are quite fascinating. This would cause one to

wonder if Luke intentionally depicted Paul’s narrative in congruence with Jesus’ for the

sake of rendering Paul as the primary inheritor of Christianity. However, when

considering the fact that Jesus heals a lame man (Lk. 5.17-26), so does Peter (Acts 3.110); power left Jesus, resulting in healings (Lk. 6.19), so also Peter (Acts 5.15); Jesus

raised the dead (Lk. 7.11-17), so also Peter (Acts 9.36-43); Jesus east out demons (Lk.

4.31-37) 64 , so also Peter (Acts 5.16); perhaps it might be more appropriate to claim that

Luke was simply trying to portray that all of the apostles were inheritors of Christianity.

Although Luke's gospel presents Jesus as uniquely providing salvation whilst always

heading to Jerusalem, ending his gospel there (24.52-53) and Acts presents Jesus as

providing salvation through the Apostles, commencing the story in Jerusalem (1.4, 8, 12),

thereafter progressively moving away from Jerusalem, nevertheless through the journeys,

Jesus is revealed in his authority, the healings helping to establish him, not as a paradigm

but as a unique, inimitable phenomenon Luke deliberately portrays the mission of the

church in continuity with the pattern of Jesus' ministry in respect of healings. 65

64

65

L.T. Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles, (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1992), p. 72,

M. Turner, The Holy Spirit and Spiritual Gifts: Then and Now (Carlisle: Paternoster, 1996), p. 25

Comment [JB35]: Ialways

thoughtthiswasprettyclear

actually.

Nonetheless, there is tension around the subject matter of who is indeed the successor of

Jesus. Some Christian denominations believe Peter to be the successor and other argue

for the case of Paul. This dynamic of succession is different from that of the Islamic

transition because Muhammad’s father is considered to be the successor by all Muslims.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is important to note that Donner culminates his argument with,

what he calls, an “alternative reading” of Muhammad’s life. His solution does not

completely accept nor discredit Ibn Ishaq’s entire work; he believes this to be going too

far. Instead, he supposes that the only way to get to near the true narrative is to constantly

wrestle with the text and the scholarship that succeeds the text. He says that’s the solution

is “to utilize the traditional narratives sparingly and with caution”. 66 Sadly, unlike the Q

source in Christian scholarship, there has yet to be a text discovered that is behind the Ibn

Ishaq text serving as its informant. Thus, I personally ascribe to Donner’s idea that: “the

truth must lie somewhere in between”. 67 Thus, it is my suggestion that the solutions

search for the narratives of both of the true historical Muhammad and Jesus also lies

somewhere in between the myths, narratives, meta-narratives, and hearsay that surrounds

the figures. Like Donner’s suggestion, I also find it extremely problematic for one to seek

to discover a true or correct narrative because such would also be flawed because the

intentions of the discoverer could potentially contaminate the lens through which truth is

conveyed. Furthermore, the labeling of one particular discovery as “the” correct version

would require a sort of re-indoctrination and cultivation towards a new doctrines that

could lead to a great deal of controversy and idealism. Thus, if Donner’s assertion that

the truth lies somewhere in between” 68 is true, there is no true way to completely separate

myth from truth. For this reason, it is my postulation that the closest that one can ever get

to knowing the true narrative of Jesus and Muhammad is for one to continuously wrestle

with the particulars that are at tension.

66

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 52.

67

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 52.

68

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass: The

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 52.

Comment [JB36]: Whichiswhat

everyreligionhasdonewithits

textscenturiesinandcenturies

out.

Comment [JB37]: Inscholarship

andinlifethisisoftenthecase.