Measuring young people's time-use in the UK Millennium Cohort

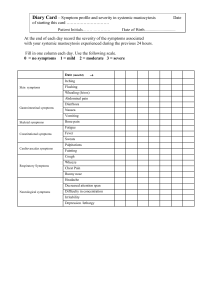

advertisement