Memories of Living on the Lower East Side Yvette Pollack In

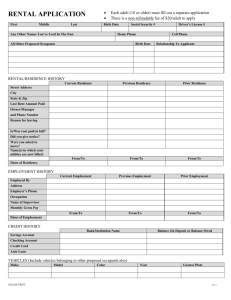

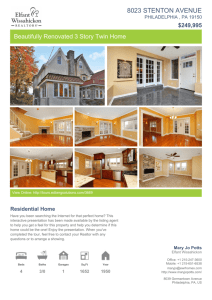

advertisement

Memories of Living on the Lower East Side Yvette Pollack In January of 1949, my husband Max and I were informed by the New York City Housing Authority that we had qualified for immediate occupancy of an apartment at 465 East 10th Street, just off Avenue D. We rejoiced at finally moving into our own home with our three-month-old baby daughter Debby. Ever since Max’s discharge from the army two years before, we had occupied the living room of my parent’s Upper West Side apartment (only forty blocks from where I now live) and it had been a very stressful experience. After World War II, there was a building boom of low and middle-income housing in New York Citywhich gave priority to the returning GI’s. The area of Manhattan which probably saw the most growth of these new apartment buildings was the Lower East Side. Of a dozen or so complexes, the following four comprised my immediate community. Stretching from East Houston Street to Fifth Street were the Lillian Wald Houses, a lowincome housing project sponsored by the New York City Housing Authority, and named for a well-known local social worker and the founder of American Community Nursing. Continuing north was my NYCHA project, Jacob Riis, named for a prominent photojournalist who had written definitive books on housing for the poor; this covered Sixth to Twelfth Streets. Directly following was Stuyvesant Town, a middle-income development sponsored by Metropolitan Life Insurance. And finally, running to Twenty-Third Street, was PeterCooperVillage, another Met Life property, but in an even higher high-price category. Note the difference in the titles of these complexes: whether one was known as a project or a town or a village was determined partly by its snob value, but mainly by its rent range. The location of all these buildings was between First Avenue and the East River Drive and although the “village” and the “town” residents paid two to five times the monthly cost of those who lived in the projects, we all had the same breathtaking view of the East River. My move to Avenue D and Tenth Street had not delighted my mother, since she had lived on Avenue B and Eighth Street thirty years before, upon her arrival in the U.S. from a shtetl in Poland. She was proud of having, after her marriage in 1912, moved uptown to the more posh Washington Heights, like so many other European émigrés had done. However, she really wept when my niece, on the occasion of her new marriage in 1962, moved to Stuyvesant Townon First Avenue and Fourteenth Street. My mother’s hysteria was caused by her conviction at that time that her daughter and granddaughter were failures because they had not made it out of the area of her humble American beginnings over a period of fifty years. I wonder if she would have had more positive feelings about her daughter’s and granddaughter’s living quarters if she had lived long enough to know that the apartment for which my niece had paid $210 in 1968 had had its rent increased in 2003 to $2100! Our building was only one block west of the waterfront. At night, when I sat silently and contentedly feeding my baby, I would gaze in wonderment at the boats silently gliding down the East River, their lights blinking in the darkness. It was fairyland. At first our rent was fifty six dollars a month, including utilities. When Max had to take a medical leave from job and school because of a broken ankle, and our income practically disappeared, our rent was reduced to half of that. Do the math; it really did cost us only twenty eight dollars for a two-bedroom flat while our neighbors just a few blocks north at Stuyvesant were paying $120. Our rooms, of course, were minuscule. Upon entering the apartment for the first time, we stood in what we assumed was the foyer, and wondered where the living room was: slowly we perceived that we were actually in it. Another big difference between “the projects” and their more affluent Lower East Sidedenizens was that we had no doors on any of our closets. While I was clumsily, but proudly, sewing some cheap monk’s cloth to drape over all of these openings, in a futile attempt to keep some of the fierce dust off our clothes, my husband was equally proudly laboring over the construction of our first piece of furniture—a coffee table built of a huge slab of butcher block with stovepipe legs. The rest of our furniture was what my generation referred to as “early relatives’or ‘Bronx Renaissance’, similar to what young, struggling couples today rely upon IKEA to furnish their first apartments. This area of town was mostly unfamiliar to me, except for the stories about Delancey and Hester Streets, which were always scorned by the nouveau-riche Jewish uptowners as the poorer immigrants’ filthy dwelling places. I excitedly set out to discover its wonders instead of sitting on the benches in front of our building with the other young mothers, whose life seemed to be totally limited to housework, childcare, shopping and mah jong. I would spend most of my days pushing a carriage with a quietly sleeping infant all over this mystical strange new world. I was immediately drawn to the street-corner barrels of Gus the Pickle Man since my father’s name was also Gus and he, too, sold pickles, but inside, in his uptown delicatessen store. I remember how proud Dad had been when I, at the age of eight, wrote my first poem to be hung above his huge pickle barrel: A nickel a shtickel is a good old rhyme. But now the same pickle will cost you a dime. When I tried to recite this rhyme to the other Gus, he was visibly unimpressed. My nose eagerly followed other neighborhood smells to the shops that sold Polish kielbasa and freshly ground Hungarian paprika and other ethnic delicacies I'd never before been exposed to.But the smell and taste that linger most strongly in my memory are of the goodies in the varied local bakeries. I have never been able to duplicate the tantalizing aromas of the familiar freshlybaked Jewish crusty rye bread laden with caraway seeds, and the more exotic tastes of the newlyfound Italian canoli and tiramisu. It was all magic to my twenty-three-year-old self, so eager for all these new adventures. And shopping at the alluring pushcarts on Avenue C truly made me feel I was in another country, and at a previous time in history. I must confess, however, that I was motivated to do this roaming also because of my attitude towards the people I lived amongst. Despite my Marxist theoretical respect for the proletariat, I also regarded them with an intellectual disdain based on a surety that this low-income project was not to be our permanent residence. ( I had no way of knowing then that, ten years later when we had made the leap from public housing to a posh Long Island neighborhood, I would have far less respect for the suburban snobs there than, when I’d been less mature, for the honest working class families I had once scorned living amongst.) I knew that, as soon as Max finished college and became a professional, we would be able to leave this stop-gap home, unlike the blue and the white-collar neighbors whom I regarded as lifetime prisoners there. Even after fifty-four years, I can still close my eyes and visualize the Sunday parade of local residents walking along the riverbank and shopping on the avenues. As the various groups merged in their meanderings, my husband and I played a guessing game to try to figure out who lived in each of the red-bricked skyscrapers, all looking alike from the outside. We finally decided that the richer locals were the ones wearing jeans, then known as dungarees, since their workweek clothing code was suits and ties in their roles as teachers, lawyers and similar middle class professions. Contrariwise, the project populaces were decked out in their weekend finery of suits and ties and high-heeled shoes for the women, since they'd had to wear more casual outfits or even uniforms, in their jobs, mostly in factories, offices, fire houses, police stations and post offices. I wonder if such clothing distinctions exist there still, or anywhere else in New York. After three years at Jacob Riis, by the way, we did indeed move onward and upward: to a middle-income housing development in Flushing, Queens; then to an expensive house and garden in suburban Great Neck. Finally, after the divorce in 1970, I moved back to Manhattan, into an apartment in a middle-income, state subsidized building on the Upper West Side, back to my beginnings. And here I have lived so happily and comfortably for the past forty years. I have never been willing to make a pilgrimage to my old stomping-grounds, knowing that time has wrought so many changes there and I might not recognize too many of the familiar landmarks. And I must admit that I would rather treasure the possible unreality of my memories than risk being confronted with the realities of those changes. I do, however, have contact with quite a few of its current residents, most of whom now refer to this area as “Alphabet City”, and have been both amused and bemused to learn that it has become a choice location for many upwardly mobile young people, with its excellent and expensive restaurants and its shockingly high rents. I wonder how many of them are as familiar with, or even as interested, as I am, in their neighborhood’s ethnic and economic history and development.