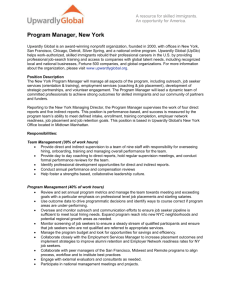

establishing the dimensions, sources and value of job seekers

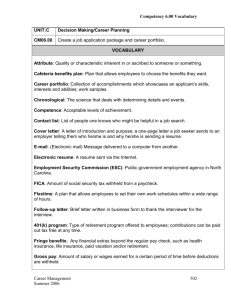

advertisement