Operative Risk in Patients with Liver and Gastrointestinal Diseases

advertisement

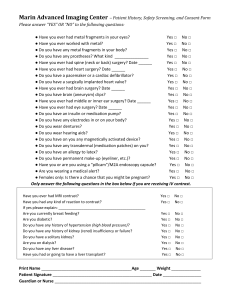

MEDICINE REVIEW ARTICLE Operative Risk in Patients with Liver and Gastrointestinal Diseases Part 3 in a Series on Preoperative Risk Assessment Jochen Rädle, Bettina Rau, Stefan Kleinschmidt, Stefan Zeuzem SUMMARY Introduction: Surgical procedures are common in patients with liver and gastrointestinal diseases, but perioperative risk and surgical contraindications in these patients, especially those with liver cirrhosis, are poorly understood. Methods: Selective literature review. Results: Perioperative risk assessment is based on the Child-Pugh or MELD score in patients with liver cirrhosis. Elective surgery is usually well tolerated in patients with chronic liver disease without cirrhosis or in those with Child A cirrhosis. Patients with Child B cirrhosis are at moderate perioperative risk while elective surgery is contraindicated in patients with Child C cirrhosis or a MELD score 14, due to high perioperative mortality. Patients with gastrointestinal disease appear to have a highly variable operative risk, which depends on the organs affected, disease severity and extent of the proposed surgical intervention. Inflammatory or acute onset gastrointestinal diseases are particularly prone to result in emergency surgery due to the severity of the clinical picture. Discussion: Patients with advanced liver disease have a high perioperative risk due to hepatic and other organ dysfunction. In contrast, gastrointestinal diseases rarely constitute a contraindication to surgery in other organ systems. Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21. Key words: operative risk, mortality, chronic liver diseases, liver cirrhosis, gastrointestinal diseases H epatological and gastroenterological diseases rarely constitute particular risk factors in operative procedures. Cardiopulmonary disorders and progressive hepatic disorders are primarily regarded as relative or absolute contraindications or result in modification of the operative method. Few prospective studies that deal with this topic have been performed to date. In this article, we attempt to define the operative mortality risk for surgery on central organ systems, which usually requires full anesthesia, on the basis of a selective review of the currently available literature. Procedures that bear a lower risk and are performed under local or regional anesthesia are not taken into account. In addition to the underlying illness and the operation itself, we determined the operative risk especially from comorbidity due to internal causes and the patient's age. The operative risk rises notably with the age of the patient (e1–e5). A simple risk assessment can be done independently of the patient's age, by using the ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score (e6–e8). In addition to the risk associated with anesthesia, this score correlates well with the duration of general morbidity and mortality (e9, e10) (table 1). By contrast, the rather scientifically used POSSUM (Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enumeration of Mortality and morbidity) score and improved Portsmouth-POSSUM score capture several physiological and operative variables that help in assessing individual mortality and prognosis (1, 2). Liver Operations in patients with existing liver disease are not uncommon. Some 10% of such patients are being operated on during the last two years of life (e11, e12). The extent of the Klinik für Innere Medizin II, Universitätsklinikum des Saarlandes, Homburg/Saar: PD Dr. med. Rädle, Prof. Dr. med. Zeuzem; Klinik für Allgemeine Chirurgie, Viszeral-, Gefäß- und Kinderchirurgie, Universitätsklinikum des Saarlandes, Homburg/Saar: PD Dr. med. Rau; Abteilung für Anästhesie, Intensivmedizin und Schmerztherapie, BG-Unfallklinik Ludwigshafen: Prof. Dr. med. Kleinschmidt; Medizinische Klinik I, Klinikum der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt a. M.: Prof. Dr. med. Zeuzem Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 1 MEDICINE TABLE 1 Risk assessment according to the classification of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) for elective surgery (ASA I–V) and emergency operations (ASA Ie–Ve; e: emergency) (e6–e8) Group Criteria Systemic diseases (examples) ASA I Healthy patient – ASA II Patient with mild systemic disease without impaired functioning Moderate hypertonus; moderate diabetes not requiring insulin ASA III Patient with severe systemic disease with impaired functioning Compensated and decompensated heart failure; chronic respiratory insufficiency; severe diabetes with complications; cirrhosis of the liver; chronic renal insufficiency ASA IV Patient with severe systemic disease that is life threatening with or without surgery Striking decompensated heart failure; severe malignant hypertonus; shock and coma of different genesis; progressive hepatic and renal insufficiency ASA V Moribund patient who is not expected to survive the following 24 hours with or without surgery Severe systemic disease with immediate risk of death (e.g., fulminant pulmonary embolus; extensive myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock) liver damage and the actual operation are the main influential factors. Further risk factors are a delayed metabolism of anesthetics/pharmaceuticals, altered perioperative hemodynamics (volume load, hypotonus, reduced perfusion of the liver) and a higher postoperative risk because of existing liver disease (3, 4). In liver surgery, improvements in preoperative diagnostics, selection of patients, operative technique, administration of anesthesia, and intensive care, as well as by concentrating these interventions in high volume centers have reduced mortality to less than 5% (5–7). Parameters for risk assessment Liver function tests – Liver function tests are not suitable for risk assessment, with the exception of synthesis and excretion parameters. In combination with clinical symptoms they are useful in identifying hepatopathies (box 1) (e13). Scoring systems – Since the liver has several functions, systems have been developed that assess partial functions separately and relate the overall score to the mortality risk. The best known of these prognostic scores is the Child-Turcotte-Pugh classification, first developed by Child and Turcotte in 1964 and modified by Pugh in 1973 (table 2) (e14–e16). Although encephalopathy and amount of ascites are undergoing subjective assessment and a deterioration of the clinical condition is not always reflected in a change in classification, in patients with liver cirrhosis it correlates well with perioperative mortality in very different operations (8–13). The MELD (model for end stage liver disease) score is based on 4 objective clinical parameters (box 2). This score was developed in 2000 as a mathematical model in patients with liver disease to estimate the 3 month survival rate before TIPS implantation (14). The score correlates well with overall mortality, captures individual changes in the course of the disease, and is therefore used for organ allocation for liver transplantations. It is suitable as the predictive parameters for perioperative morbidity and mortality in different procedures (e17–e22, 15, 16). Quantitative liver function tests – Different testing systems have been developed to quantify liver function (box 1). Prospectively, good correlations with the existing liver function were found particularly for the indocyanine green plasma disappearance rate and 99mTc GSA scintigraphy (17). These liver function tests are used for the preoperative assessment in some centers (5, 7), but they are not suitable for generally used routine diagnostics. Assessing the operative risk The operative risk in patients with liver disease is shown on the basis of 3 clinical situations: A patient has raised liver function tests without known liver disease: This occurs at a rate of 1:300 to 1:700 in otherwise "healthy" candidates for surgery (e23, e24). If a Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 2 MEDICINE single value is raised – for example, GPT, gamma GT, or AP – the operative risk is not increased (e13, 18). Asymptomatic patients with several raised liver function test results usually have relevant liver disease but rarely liver cirrhosis beyond Child-Pugh stage A. Such patients thus have no increased operative risk. Patients with known, functionally stable liver disease: These patients have no increased operative risk in routine surgery (3, 4). Even in liver resections, patients with Child-A cirrhosis of the liver have no increased mortality compared with controls (3.5% versus 3.0%) (9). In hepatic steatosis, mortality increases as a rule only in liver resection, according to the extent of the steatosis (>10% if the liver fat content exceeds 30%) (e 25, e26). Patients with symptomatic liver disease: In progressive liver disease or decompensated cirrhosis, the perioperative risk of complications, morbidity, and mortality is notably increased. However, many studies documenting this date back several years now (3, 4, 8–13, e27). These days in perioperative management, pathophysiological changes in other organ systems – such as the cardiovascular, lung, kidney, brain, and metabolic systems – are being taken into consideration (table 3). The extent of such secondary organ damage is as decisive for the operative risk as the primary liver function impairment. In non-hepatic operations, the mortality risk for severe encephalopathy increases by a factor of 35 (e28). Perioperative improvement of the patient's clinical condition – such as therapy of coagulatory disorders, ascites, encephalopathy, hyponatremia, and impaired renal function – may prevent complications especially in Child-B and Child-C patients and reduce the operative risk. In cachectic patients, preoperative parenteral feeding may be useful (e29– e33). In addition to the extent of protein binding, pharmacological aspects of medical drugs relevant for anesthesia and analgesia have to be taken into consideration. Newer volatile anesthetics, such as BOX 1 Laboratory parameters and quantitative function tests for the characterization of liver function (e13, e78–e80, 17) Laboratory parameters Testing hepatocellular integrity: GOT (AST) GPT (ALT) GLDH Testing excretion function and cholestasis: Bilirubin in serum (direct, indirect) Alkaline phosphatase (AP) Gamma glutamyl transferase (gamma GT) Testing synthesis function: Albumin Cholinesterase (CHE) Quick (INR), PTT Individual coagulation factors (e.g., ATIII, Factor II, V) Quantitative function tests Testing excretory and metabolic capacity: Indocyanine green (ICG) plasma disappearance rate*1 Aminopyrine breath test*2 Monoethylglycinexylidide lidocaine test (MEGX test)*2 99mTc galactosyl serum albumin (GSA) scintigraphy*2 *1 Evaluates excretory transport capacity for anorganic ions in analogy to serum bilirubin values *2 Evaluates metabolic capacity in analogy to uric acid synthesis GOT, glutamate oxalacetate transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GPT, Glutamate pyruvate transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GLDH, Glutamate dehydrogenase; INR, international normalized ratio; PTT, partial thromboplastin time Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 3 MEDICINE desfluran and sevofluran, affect arterial liver circulation only slightly; but decreased portal vein flow can be expected (18). Most induction anesthetics – for example, barbiturates and propofol – result in generally reduced liver circulation. Intraoperatively and perioperatively, stable hemodynamics should therefore be guaranteed. In addition to further reduced liver function after the operation, surgical, infectious, or bleeding-related complications have to be considered. Operative risk and choice of method – In asymptomatic patients with liver disease, no limitations apply for operative procedures; but particular attention might go to the liver disease perioperatively and in managing anesthesia. In symptomatic patients, the liver disease has to be considered in the context of the operative risk assessment. This is the case for the indication and urgency of the procedure, as well as the choice of surgical method. The risk is higher in abdominal surgery, especially in portal hypertension, than in extraabdominal operations. Surgery of the liver itself has to be differentiated from surgery of other abdominal organs. Liver transplantation in the context of fulminant hepatitis or end-stage chronic liver disease are special cases. Emergency surgery – Interventions performed to save lives by definition are unequivocal with regard to the necessity for and urgency of surgery. Independent of the risk of injury, in patients with cirrhosis of the liver, emergency laparotomy increases the risk of complications and the duration of postoperative intensive care (19). Altogether, mortality may be expected to be up to 50% (10% in Child-A, 30% in Child-B, 82% in Child-C) (18% for elective surgery) (8), which rises further postoperatively over 3 months (mortality after 1 month/ 3 months; emergency surgery: 19%/44%; elective surgery. 17%/21%) (12). Elective procedures – In elective procedures, liver function impairment has to be factored into the risk assessment. This may determine the decision in favor of surgery or selection of surgical method. In abdominal non-hepatic surgery, 30 day mortality in patients with cirrhosis of the liver is raised 4-fold (16.3% versus 3.5% in patients without liver disease). This is determined by the Child-Pugh classification (Child-A 4%, Child-B 32%, Child-C 55%), the time taken by the surgery, and the general postoperative complications (10). Child-C cirrhosis as well as severe coagulopathy or extrahepatic complications are regarded as contraindications. Surgical interventions to the hepatobiliary system are an exception in liver disease. The operative treatment – for example, resection, liver transplantation – of TABLE 2 Child-Pugh classification (e15) of cirrhosis of the liver and surgical risk on the basis of the literature reviewed (e11, 3, 4, 8, 10) Parameter Points 1 2 3 Albumin (g/dl) > 3.5 2.8–3.5 < 2.8 Bilirubin (mg/dl) <2 2–3 >3 (in primarily biliary cirrhosis) Quick value (%) (alternatively INR) <4 4–10 > 10 > 70 40–70 < 40 < 1.7 2.3–1.7 > 2.3 Ascites None Mild; responds to treatment Severe; resistant to treatment Encephalopathy None Stages I–II Stages III–IV Child-Pugh classification A B C Points 5–6 7–9 10–15 Operative risk <1% ca. 10 % > 50 % 1 year mortality (%) 3–10 % 10–30 % 50–80 % Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 4 MEDICINE hepatocellular carcinoma is determined by liver function, extent of the tumor, and location of the carcinoma. Mortality for resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in a cirrhotic liver has been reduced to less than 5%, thanks to an improvement in patient selection (that is, a preference for Child-A and Child-B patients, considering the liver function reserve, and comorbidity) and to modern techniques (for example, preoperative ligation or embolization of the portal vein, 3-D simulation, calculation of residual liver volume, improved surgical resection techniques). In liver transplantation, the rate is about 10% (5, 7, 20, 21, e34, e35). The indication for cholecystectomy is made in people with healthy livers, because recent studies have reported mortality figures of <1% for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Child-A and Child-B patients (22, e36, e37). Surgery on organs far removed from the liver present the main proportion of all elective surgery in patients with liver disease. Surgery to the extremities or peripheral vasculature is usually tolerated well, but cardiac surgery or operations on larger abdominal or thoracic vessels are associated with a higher rate of complications and mortality (e27, e38, e39). Decisions in favor of operative or less invasive treatment methods should be taken with patients and/or relatives, depending on the liver function and the existing finding while considering the quality of life and life expectancy. Esophagus and stomach Patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease often have bronchopulmonary complications, for example, aspiration with subsequent pneumonia. These should be taken into consideration when introducing anesthesia (rapid sequence induction technique). Stomach ulcers and duodenal ulcers can easily be treated with drugs and present a lesser perioperative risk factor. In many bigger surgical procedures or in risk patients (for example, with a history of ulcers, Helicobacter-associated gastritis, medication with non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs), the perioperative ulcer prophylaxis with a proton pump inhibitor is standard treatment. If in a scenario of an upper gastrointestinal bleed that cannot be stopped endoscopically or interventionally surgery to stop the bleed is required, mortality is 5–17% depending on the resection method (e40). In spite of numerous technical improvements, elective esophageal surgery ranges among the complication prone intestinal surgical procedures even in experienced centers – the Box 2 Calculation of MELD score The calculation of the MELD score is done on the basis of 4 objective clinical parameters (bilirubin, coagulation [INR], creatinine, and etiology of liver disease) (14, e17). The etiology of the liver disease is scored with 1 point in case of lacking prognostic relevance. When liver resection, cholecystectomy, or cardiac surgery is performed, a score 8 (while taking into consideration the etiology of the liver disease) is associated with notable perioperative morbidity. On the basis of the current calculation without considering etiology, a MELD score 14 is associated with a notably higher perioperative risk (15, 16, e18–e22). MELD-Score = 3.8 11.2 9.6 6.4 x x x x ln(Bilirubin in mg/dL) ln(INR) ln(creatinin in mg/dL) Etiology Evaluation of etiology: + + + cholestatic or alcoholic = 0 Other = 1 Internet-based calculation possible under http://www.mayoclinic.org/gi-rst/mayomodel5.html (initial model) or http://www.mayoclinic.org/gi-rst/mayomodel6.html (current United Network for Organ Sharing Modification) Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 5 MEDICINE TABLE 3 Possible pathophysiological changes in other organ systems subsequent to existing liver disease (3, 4, 18) System Pathophysiological change Cardiovascular Cardiac time volume raised Blood volume raised Peripheral vascular resistance lowered Tendency to hypotonus Pulmonary Hypoxemia (hepatopulmonary syndrome) Pulmonary arterial pressure raised (portopulmonary hypertonus) Emphysematous restructuring (e.g., in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency) Renal Renal blood flow lowered Glomerular filtration rate lowered (hepatorenal syndrome) Aldosterone raised Cerebral Glial edema owing to toxic effects (hepatic encephalopathy) Sensitivity to opioids raised Metabolic-systemic Thrombopenia, thrombasthenia Hypocoagulability and hypercoagulability Hypalbuminemia Hyponatremia Lowered serum cholinesterase Hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia Lowered uric acid synthesis Reduced proliferation of osteoblasts (osteopathy) Drug metabolism restricted Endotoxin clearance restricted minimum morbidity and mortality are 30% and 5%, respectively (e41, e42). In addition to a concentration in high volume centers, a treatment algorithm that is adapted to the risk profile of the patient (composite risk score) has mainly contributed to lowering morbidity and mortality. If this algorithm, which has been prospectively evaluated by Siewert et al., is included in the indication and selection of resection method (one or two stage procedure), hospital mortality for esophageal resection can be lowered from 16% to 5% owing to better selection of patients (23). The main risk factors include age, Karnofsky index, ASA score, proximal location of tumor, and intraoperative blood loss (e43). Similar risk factors exist for gastrectomies (e10). The preoperative risk profile should therefore be included into any treatment decision. For the treatment of esophageal malignancies, equivalent, non-surgical, therapeutic options exist, with regard to survival and quality of life (e44, e45). Colon In patients with chronic inflammatory colon disorders, elective resection or colectomy are not associated with relevant perioperative mortality (e46, e47). Long term pretreatment with steroids (prednisolone >20 mg/day), other immunosuppressive drugs, or infliximab do not increase perioperative mortality (e48–e50). Severe pancolitis, colonic bleeds that cannot be managed endoscopically or interventionally, abscesses, toxic megacolon or perforation require immediate surgical treatment. Perioperative mortality in toxic megacolon is 16% (e51). Severe pseudomembranous or ischemic colitis – itself associated with mortality of up to 15% – can result in emergency colectomy with a raised mortality risk, if conservative treatment fails (e52, e53). For surgical treatment of colorectal cancer, age (>70 or 80 years), a high ASA or APACHE-II score, anemia, and emergency surgery were found to be risk factors for an increase in perioperative mortality by 10–20% (e2, e3, e5). In elective surgery to the colon, however, in the context of "fast track" surgery, a standardized sequence of useful perioperative measures – for example, atraumatic surgical technique, avoidance of hypovolemia and hypoxia, sufficient analgesia, and early mobilization and nutrition – markedly improved the complication rate and particularly the postoperative reconvalescence (e54). Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 6 MEDICINE TABLE 4 Gastroenterological disorders with severe and relative contraindications for elective surgery to other organ systems Contraindications for elective surgical procedures Disorders that may result in an indication for urgent surgery Severe Acute pancreatitis Gastrointestinal hemorrhage Acute mesenteric ischemia Peritonitis Acute cholangitis Paralytic ileus Acute infectious enteritis Infected necroses Therapy refractory hemorrhage Intestinal gangrene Perforation of intestinal organ Acute cholecystitis Appendicitis Mechanical ileus Relative Florid stomach or duodenal ulcer Diverticulitis Severe colitis – Ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease – Ischemic colitis – Pseudomembranous colitis Severe reflux esophagitis Intestinal pseudo-obstruction Malnutrition Bleeding ulcer refractory to therapy, perforation of ulcer Perforated diverticulum Toxic megacolon, perforation of colon Because of their severity or in disease specific complications, () these disorders may themselves result in an urgent surgical indication. Pancreas In contrast to the clinically mild edematous form, severe acute pancreatitis is still associated with a total mortality of 10–20% (e55). The main risk factors include organ failure that is refractory to treatment in the early phase (e56, e57) and later infection of the pancreatic necroses (e58). The severity of the organ failure becomes increasingly important compared to a necrosis infection (e57, e59). In infected necroses that are refractory to therapy, necrosectomy is required after 3 to 4 weeks, which is associated with a mortality of 20–30% (e60). Further relevant risk factors are obesity, the patient's age, comorbidities, and the need for surgery soon after onset of illness (e59, e61–e63). Chronic pancreatitis does not present an operative risk factor, provided that substitution therapy is sufficient. In large patient series, even in pancreatic malignancies no relevant surgical risk factor was assessed that was associated with increased mortality. When patients were older than 70, only the complication rate due to comorbidities was 25% higher (e64–e67). The influence of surgical and location-related factors on postoperative mortality and morbidity after pancreatic resection has been amply documented (e64, e65). Acute porphyria The 4 forms of acute porphyria present as acute, life threatening illness that manifest with gastrointestinal, neurological, and cardiovascular symptoms and are often difficult to diagnose. Smoking, fasting, infections, operations, or pharmaceuticals – for example, barbiturates – may result in an acute episode. Elective surgery can mostly be undertaken without any problem, as long as disease triggering drugs and long periods of no food intake are avoided, glucose is administered continually during the operation, and postoperative monitoring is extended (e68–e70). However, the operative risk for a patient with previously undiagnosed porphyria is almost impossible to assess. Nutritional status The importance of a reduced nutritional status for the perioperative rate of complications, morbidity, and mortality has been well documented (24, 25). A reduced physical and mental state, lowered immunity, and delayed wound healing are sequelae of malnutrition. For the evaluation of the nutritional status, the methods listed in the additional table (see additional material at the end of this article) are recommended. To prepare for abdominothoracic operations, in patients with a nutritional deficiency, parenteral hyperalimentation for 7 to 14 days, and an adequate substitution of vitamins and Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 7 MEDICINE DIAGRAM How to proceed in patients with liver disease and planned surgical procedure (adapted from 4) *1Current calculation without taking into consideration the etiology of the liver disease (box 2) *2Because of high mortality, individual decision possible especially in emergency procedures minerals are effective. Recent studies show a reduced complication rate after abdominothoracic surgery after administration of preoperative oral supplementation (liquid food for 5 to 7 days) even in patients of normal weight (e71-e74). Early parenteral or oral feeds are associated with a reduction in infectious complications and a shorter stay in hospital (e75). However, this effect is often smaller than that associated with preoperative supplementation. Clearly overweight patients (BMI >30) also have more operative and perioperative problems, for example, poor wound healing, cardiac comorbidities, thrombo-embolic complications. Postoperatively, adequate thromboprophylaxis and regular control of the surgical wound and cardiac function are required (e76, e77). Gastroenterological disorders: risk during surgery to other organ systems Gastroenterological disorders include a wide range of different disorders that require different therapies. The risk is determined particularly by the severity of the illness and the kind of operation that is planned. This is also the case for procedures without a direct association to the underlying illness. Chronic, clinically stable and easy to treat diseases are included with the general comorbidities during the perioperative risk assessment and usually do not pose a particular risk factor. The disease status should, however, be evaluated preoperatively by using suitable laboratory chemistry, imaging techniques, or endoscopic procedures; and the same is true for the existing drug treatment. In individual gastroenterological disorders that are characterized by acute onset or high inflammatory activity (table 4), surgery should not be undertaken during the acute phase. An improvement in the disorder should be worked towards by using specific treatment and then one should wait until this improvement has occurred. But these disorders may themselves lead to urgent surgical indications-as a result of life threatening complications and failure of the drug or interventional therapy-which may even be associated with clearly increased perioperative mortality. The disorders listed in table 4 may be regarded as Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 8 MEDICINE contraindications for other surgical procedures. However, especially in emergencies, the individual case should be assessed independently. Conclusion Severe or progressive illness can markedly increase the risk of operative procedures. In view of current medical options, absolute contraindications have become less important in favor of relative contraindications. Whereas patients with Child-A cirrhosis have no increased operative risk and patients with Child-B cirrhosis a moderately increased risk, elective operations are usually contraindicated in patients with Child-C cirrhosis or a MELD score 14 because of considerable mortality (diagram). Liver transplantation in acute or chronic liver failure is a special case, however. In high risk patients, a targeted improvement in their clinical condition before an operation may prevent complications or enable operability. The cornerstones of this management are based on perioperative therapy of complications of the liver disease (coagulopathy with bleeds, ascites, encephalopathy, impaired renal function, and malnutrition). In addition to an improved preoperative identification of risk patients with scoring systems or liver function tests, perioperative morbidity and mortality can be lowered further through anesthesiological management, i.e., selection of drugs, volume management, and avoidance of hypotonus. Improved surgical techniques – such as procedures to transect the hepatic parenchyma and reduce intraoperative blood loss, as well as comprehensive interdisciplinary care delivered from all involved specialties – improve perioperative morbidity and mortality. Gastroenterological disorders include a wide range of different diseases that entail a very variable perioperative risk. While clinically stable disorders have a secondary role in perioperative risk assessment, elective surgery should be avoided in a scenario of severe inflammation or acute onset of illness. In the context of current medical treatment options, however, only few gastroenterological disorders present serious contraindications. Conflict of Interest Statement The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the Guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Manuscript received on 3 August 2006, final version accepted on 17 April 2007. Translated from the original German by Dr Birte Twisselmann. REFERENCES For e-references please refer to the additional references listed below. 1. Copeland GP, Jones D, Walters M: POSSUM: a scoring system for surgical audit. Br J Surg 1991; 78: 355–60. 2. Prytherch DR, Whiteley MS, Higgins B, Weaver PC, Prout WG, Powell SJ: POSSUM and Portsmouth POSSUM for predicting mortality. Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 1217–20. 3. Friedman LS: The risk of surgery in patients with liver disease. Hepatology 1999; 29: 1617–23. 4. Keegan MT, Plevak DJ: Preoperative assessment of the patient with liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100: 2116–27. 5. Wu CC, Yeh DC, Lin MC, Liu TJ, P'Eng FK: Improving operative safety for cirrhotic liver resection. Br J Surg 2001; 88: 210–5. 6. Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y et al.: Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1,803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg 2002; 236: 397–406; discussion –7. 7. Imamura H, Seyama Y, Kokudo N et al.: One thousand fifty-six hepatectomies without mortality in 8 years. Arch Surg 2003; 138: 1198–206; discussion 206. 8. Mansour A, Watson W, Shayani V, Pickleman J: Abdominal operations in patients with cirrhosis: still a major surgical challenge. Surgery 1997; 122: 730–5; discussion 5–6. 9. Capussotti L, Polastri R: Operative risks of major hepatic resections. Hepatogastroenterology 1998; 45: 184–90. 10. del Olmo JA, Flor-Lorente B, Flor-Civera B et al.: Risk factors for nonhepatic surgery in patients with cirrhosis. World J Surg 2003; 27: 647–52. 11. Franzetta M, Raimondo D, Giammanco M et al.: Prognostic factors of cirrhotic patients in extra-hepatic surgery. Minerva Chir 2003; 58: 541–4. 12. Farnsworth N, Fagan SP, Berger DH, Awad SS: Child-Turcotte-Pugh versus MELD score as a predictor of outcome after elective and emergent surgery in cirrhotic patients. Am J Surg 2004; 188: 580–3. 13. Suman A, Barnes DS, Zein NN, Levinthal GN, Connor JT, Carey WD: Predicting outcome after cardiac surgery in patients with cirrhosis: a comparison of Child-Pugh and MELD scores. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2: 719–23. 14. Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, Peine CJ, Rank J, ter Borg PC: A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology 2000; 31: 864–71. Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 9 MEDICINE 15. Befeler AS, Palmer DE, Hoffman M, Longo W, Solomon H, Di Bisceglie AM: The safety of intra-abdominal surgery in patients with cirrhosis: model for end-stage liver disease score is superior to Child-Turcotte-Pugh classification in predicting outcome. Arch Surg 2005; 140: 650–4; discussion 5. 16. Huo TI, Huang YH, Lin HC et al.: Proposal of a modified cancer of the liver Italian program staging system based on the model for end-stage liver disease for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing loco-regional therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 975–82. 17. Schneider PD: Preoperative assessment of liver function. Surg Clin North Am 2004; 84: 355–73. 18. Puccini M, Nöldge-Schomburg G: Anästhesie und Leber. Anästhesiologie & Intensivmedizin 2001; 42: 895–907. 19. Demetriades D, Constantinou C, Salim A, Velmahos G, Rhee P, Chan L: Liver cirrhosis in patients undergoing laparotomy for trauma: effect on outcomes. J Am Coll Surg 2004; 199: 538–42. 20. Burroughs AK, Sabin CA, Rolles K et al.: 3-month and 12-month mortality after first liver transplant in adults in Europe: predictive models for outcome. Lancet 2006; 367: 225–32. 21. Furrer K, Deoliveira ML, Graf R, Clavien PA: Improving outcome in patients undergoing liver surgery. Liver Int 2007; 27: 26–39. 22. Yeh CN, Chen MF, Jan YY: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 226 cirrhotic patients. Experience of a single center in Taiwan. Surg Endosc 2002; 16: 1583–7. 23. Bartels H, Stein HJ, Siewert JR: Preoperative risk analysis and postoperative mortality of oesophagectomy for resectable oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 840–4. 24. Weimann A, Jauch KW, Kemen M et al.: DGEM-Leitlinie Enterale Ernährung: Chirurgie und Transplantation. Aktuel Ernaehr Med 2003; 28 (Suppl. 1): S51–S60. 25. Kuzu MA, Terzioglu H, Genc V et al.: Preoperative nutritional risk assessment in predicting postoperative outcome in patients undergoing major surgery. World J Surg 2006; 30: 378–90. ADDITIONAL REFERENCES e1. Richardson JD, Cocanour CS, Kern JA et al.: Perioperative risk assessment in elderly and high-risk patients. J Am Coll Surg 2004; 199: 133–46. e2. Alvarez JA, Baldonedo RF, Bear IG, Truan N, Pire G, Alvarez P: Obstructing colorectal carcinoma: outcome and risk factors for morbidity and mortality. Dig Surg 2005; 22: 174–81. e3. Alves A, Panis Y, Mathieu P, Mantion G, Kwiatkowski F, Slim K: Postoperative mortality and morbidity in French patients undergoing colorectal surgery: results of a prospective multicenter study. Arch Surg 2005; 140: 278–83, discussion 84. e4. Damhuis RA, Meurs CJ, Meijer WS: Postoperative mortality after cancer surgery in octogenarians and nonagenarians: results from a series of 5,390 patients. World J Surg Oncol 2005; 3: 71. e5. Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U et al.: The impact of the risk factor „age“ on the early postoperative results of surgery for colorectal carcinoma and its significance for perioperative management. World J Surg 2005; 29: 1013–21; discussion 21–2. e6. Anon: New classification of physical status. Anesthesiology 1963; 24: 111. e7. Vacanti CJ, VanHouten RJ, Hill RC: A statistical analysis of the relationship of physical status to postoperative mortality in 68,388 cases. Anesth Analg 1970; 49: 564–6. e8. Farrow SC, Fowkes FG, Lunn JN, Robertson IB, Samuel P: Epidemiology in anaesthesia. II: Factors affecting mortality in hospital. Br J Anaesth 1982;54: 811–7. e9. Makela JT, Kiviniemi H, Laitinen S: Prognostic factors of perforated sigmoid diverticulitis in the elderly. Dig Surg 2005; 22: 100–6. e10. Sauvanet A, Mariette C, Thomas P et al.: Mortality and morbidity after resection for adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: predictive factors. J Am Coll Surg 2005; 201: 253–62. e11. Garrison RN, Cryer HM, Howard DA, Polk HC Jr.: Clarification of risk factors for abdominal operations in patients with hepatic cirrhosis. Ann Surg 1984; 199: 648–55. e12. Patel T: Surgery in the patient with liver disease. Mayo Clin Proc 1999; 74: 593–9. e13. Blum HE, Farthmann EH: Der Patient mit Hepatopathie. Chirurg 1997; 68: 763–9. e14. Child CG, Turcotte JG: Surgery and portal hypertension. Major Probl Clin Surg 1964; 1: 1–85. e15. Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R: Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973; 60: 646–9. e16. Christensen E, Schlichting P, Fauerholdt L et al.: Prognostic value of Child-Turcotte criteria in medically treated cirrhosis. Hepatology 1984; 4: 430–5. e17. Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M et al.: A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2001; 33: 464–70. e18. Wiesner RH, McDiarmid SV, Kamath PS et al.: MELD and PELD: application of survival models to liver allocation. Liver Transpl 2001; 7: 567–80. e19. Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R et al.: Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology 2003; 124: 91–6. e20. Perkins L, Jeffries M, Patel T: Utility of preoperative scores for predicting morbidity after cholecystectomy in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2: 1123–8. e21. Teh SH, Christein J, Donohue J et al.: Hepatic resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: Model of End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score predicts perioperative mortality. J Gastrointest Surg 2005; 9: 1207–15; discussion 15. e22. Schroeder RA, Marroquin CE, Bute BP, Khuri S, Henderson WG, Kuo PC: Predictive indices of morbidity and mortality after liver resection. Ann Surg 2006; 243: 373–9. Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 10 MEDICINE e23. Wataneeyawech M, Kelly KA Jr.: Hepatic diseases. Unsuspected before surgery. N Y State J Med 1975; 75: 1278–81. e24. Schemel WH: Unexpected hepatic dysfunction found by multiple laboratory screening. Anesth Analg 1976; 55: 810–2. e25. Behrns KE, Tsiotos GG, DeSouza NF, Krishna MK, Ludwig J, Nagorney DM: Hepatic steatosis as a potential risk factor for major hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg 1998; 2: 292–8. e26. Kooby DA, Fong Y, Suriawinata A et al.: Impact of steatosis on perioperative outcome following hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2003; 7: 1034–44. e27. Ziser A, Plevak DJ, Wiesner RH, Rakela J, Offord KP, Brown DL: Morbidity and mortality in cirrhotic patients undergoing anesthesia and surgery. Anesthesiology 1999; 90: 42–53. e28. Rice HE, O'Keefe GE, Helton WS, Johansen K: Morbid prognostic features in patients with chronic liver failure undergoing nonhepatic surgery. Arch Surg 1997; 132: 880–4; discussion 4–5. e29. Fan ST, Lo CM, Lai EC, Chu KM, Liu CL, Wong J: Perioperative nutritional support in patients undergoing hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 1547–52. e30. Weimann A, Kuse ER, Bechstein WO, Neuberger JM, Plauth M, Pichlmayr R: Perioperative parenteral and enteral nutrition for patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. Results of a questionnaire from 16 European transplant units. Transpl Int 1998; 11 Suppl 1: S289–91. e31. Stephenson GR, Moretti EW, El-Moalem H, Clavien PA, Tuttle-Newhall JE: Malnutrition in liver transplant patients: preoperative subjective global assessment is predictive of outcome after liver transplantation. Transplantation 2001; 72: 666–70. e32. Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, Riggio O: Malnutrition is a risk factor in cirrhotic patients undergoing surgery. Nutrition 2002; 18: 978–86. e33. Wiklund RA: Preoperative preparation of patients with advanced liver disease. Crit Care Med 2004; 32 (4 Suppl.): S106–15. e34. Capussotti L, Muratore A, Massucco P, Ferrero A, Polastri R, Bouzari H: Major liver resections for hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis: early and long-term outcomes. Liver Transpl 2004; 10 (2 Suppl. 1): S64–8. e35. Shetty K, Timmins K, Brensinger C et al.: Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma validation of present selection criteria in predicting outcome. Liver Transpl 2004; 10: 911–8. e36. Fernandes NF, Schwesinger WH, Hilsenbeck SG et al.: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and cirrhosis: a case-control study of outcomes. Liver Transpl 2000; 6: 340–4. e37. Poggio JL, Rowland CM, Gores GJ, Nagorney DM, Donohue JH: A comparison of laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy in patients with compensated cirrhosis and symptomatic gallstone disease. Surgery 2000; 127: 405–11. e38. Klemperer JD, Ko W, Krieger KH et al.: Cardiac operations in patients with cirrhosis. Ann Thorac Surg 1998; 65: 85–7. e39. Kaplan M, Cimen S, Kut MS, Demirtas MM: Cardiac operations for patients with chronic liver disease. Heart Surg Forum 2002; 5: 60–5. e40. Paimela H, Oksala NK, Kivilaakso E: Surgery for peptic ulcer today. A study on the incidence, methods and mortality in surgery for peptic ulcer in Finland between 1987 and 1999. Dig Surg 2004; 21: 185–91. e41. McCulloch P, Ward J, Tekkis PP: Mortality and morbidity in gastro-oesophageal cancer surgery: initial results of ASCOT multicentre prospective cohort study. Bmj 2003; 327: 1192–7. e42. Stein HJ, von Rahden BH, Siewert JR: Survival after oesophagectomy for cancer of the oesophagus. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2005; 390: 280–5. e43. Law S, Wong KH, Kwok KF, Chu KM, Wong J: Predictive factors for postoperative pulmonary complications and mortality after esophagectomy for cancer. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 791–800. e44. Chiu PW, Chan AC, Leung SF et al.: Multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing standard esophagectomy with chemoradiotherapy for treatment of squamous esophageal cancer: early results from the Chinese University Research Group for Esophageal Cancer (CURE). J Gastrointest Surg 2005; 9: 794–802. e45. Bonnetain F, Bouche O, Michel P et al.: A comparative longitudinal quality of life study using the Spitzer quality of life index in a randomized multicenter phase III trial (FFCD 9102): chemoradiation followed by surgery compared with chemoradiation alone in locally advanced squamous resectable thoracic esophageal cancer. Ann Oncol 2006; 17: 827–34. e46. Steegmuller KW, Schafer W, Lang E, von Flotow P, Junginger T: Perioperatives Risiko der chirurgischen Therapie des Morbus Crohn. Chirurg 1992; 63: 39–43. e47. Ghirardi M, Di Fabio F, Mariani PP, Nascimbeni R, Salerni B: Surgery in severe ulcerative colitis: our experience. Ann Ital Chir 2003; 74: 543–6. e48. Hyde GM, Jewell DP, Kettlewell MG, Mortensen NJ: Cyclosporin for severe ulcerative colitis does not increase the rate of perioperative complications. Dis Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 1436–40. e49. Bruewer M, Utech M, Rijcken EJ et al.: Preoperative steroid administration: effect on morbidity among patients undergoing intestinal bowel resection for Crohns disease. World J Surg 2003; 27: 1306–10. e50. Colombel JF, Loftus EV Jr., Tremaine WJ et al.: Early postoperative complications are not increased in patients with Crohn's disease treated perioperatively with infliximab or immunosuppressive therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99: 878–83. e51. Ausch C, Madoff RD, Gnant M et al.: Aetiology and surgical management of toxic megacolon. Colorectal Dis 2006; 8: 195–201. e52. Morris AM, Jobe BA, Stoney M, Sheppard BC, Deveney CW, Deveney KE: Clostridium difficile colitis: an increasingly aggressive iatrogenic disease? Arch Surg 2002; 137: 1096–100. Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 11 MEDICINE e53. Sreenarasimhaiah J: Diagnosis and management of ischemic colitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2005; 7: 421–6. e54. Soop M, Nygren J, Ljungqvist O: Optimizing perioperative management of patients undergoing colorectal surgery: what is new? Curr Opin Crit Care 2006; 12: 166–70. e55. Beger HG, Rau B, Isenmann R: Natural history of necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2003; 3: 93–101. e56. Johnson CD, Abu-Hilal M: Persistent organ failure during the first week as a marker of fatal outcome in acute pancreatitis. Gut 2004; 53: 1340–4. e57. Rau BM, Bothe A, Kron M, Beger HG: The role of early multisystem organ failure as major risk factor for pancreatic infections and death in severe acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 1053–61. e58. Mishra G, Pineau BC: Infectious complications of pancreatitis: diagnosis and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2004; 6: 280–6. e59. De Waele JJ, Hoste E, Blot SI et al.: Perioperative factors determine outcome after surgery for severe acute pancreatitis. Crit Care 2004; 8: R504–11. e60. Beger HG, Rau B, Isenmann R: Nekrosektomie oder anatomiegerechte Resektion bei akuter Pankreatitis. Chirurg 2000; 71: 274–80. e61. Mier J, Leon EL, Castillo A, Robledo F, Blanco R: Early versus late necrosectomy in severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Am J Surg 1997; 173: 71–5. e62. Halonen KI, Leppaniemi AK, Puolakkainen PA et al.: Severe acute pancreatitis: prognostic factors in 270 consecutive patients. Pancreas 2000; 21: 266–71. e63. Martinez J, Johnson CD, Sanchez-Paya J, de Madaria E, Robles-Diaz G, Perez-Mateo M: Obesity is a definitive risk factor of severity and mortality in acute pancreatitis: an updated meta-analysis. Pancreatology 2006; 6: 206–9. e64. Bottger TC, Engelmann R, Junginger T: Is age a risk factor for major pancreatic surgery? An analysis of 300 resections. Hepatogastroenterology 1999; 46: 2589–98. e65. Lin JW, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Riall TS, Lillemoe KD: Risk factors and outcomes in postpancreaticoduodenectomy pancreaticocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg 2004; 8: 951–9. e66. Adam U, Makowiec F, Riediger H, Schareck WD, Benz S, Hopt UT: Risk factors for complications after pancreatic head resection. Am J Surg 2004; 187: 201–8. e67. Makary MA, Winter JM, Cameron JL et al.: Pancreaticoduodenectomy in the very elderly. J Gastrointest Surg 2006; 10: 347–56. e68. Kunitz O, Frank J: Anästhesiologisches Management bei Patienten mit akuten Porphyrien. Anaesthesist 2001; 50: 957–66; quiz 67–9. e69. Anderson KE, Bloomer JR, Bonkovsky HL et al.: Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of the acute porphyrias. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142: 439–50. e70. Kauppinen R: Porphyrias. Lancet 2005; 365: 241–52. e71. Bozzetti F, Gavazzi C, Miceli R et al.: Perioperative total parenteral nutrition in malnourished, gastrointestinal cancer patients: a randomized, clinical trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2000; 24: 7–14. e72. Bozzetti F: Nutrition and gastrointestinal cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2001; 4: 541–6. e73. Salvino RM, Dechicco RS, Seidner DL: Perioperative nutrition support: who and how. Cleve Clin J Med 2004; 71: 345–51. e74. Seidner DL: Nutritional issues in the surgical patient. Cleve Clin J Med 2006; 73 Suppl 1: S77–81. e75. Fearon KC, Luff R: The nutritional management of surgical patients: enhanced recovery after surgery. Proc Nutr Soc 2003; 62: 807–11. e76. Cheah MH, Kam PC: Obesity: basic science and medical aspects relevant to anaesthetists. Anaesthesia 2005; 60: 1009–21. e77. DeMaria EJ, Carmody BJ: Perioperative management of special populations: obesity. Surg Clin North Am 2005; 85: 1283–9, xii. e78. Armuzzi A, Candelli M, Zocco MA et al.: Review article: breath testing for human liver function assessment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 1977–96. e79. Burra P, Masier A: Dynamic tests to study liver function. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2004; 8: 19–21. e80. Kokudo N, Vera DR, Makuuchi M: Clinical application of TcGSA. Nucl Med Biol 2003; 30: 845–9. e81. Kondrup J, Allison SP, Elia M, Vellas B, Plauth M: ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr 2003; 22: 415–21. e82. Schütz T, Valentini L, Plauth M: Screening auf Mangelernährung nach den ESPEN-Leitlinien 2002. Aktuel Ernaehr Med 2005; 30: 99–103. Corresponding author PD Dr. med. Jochen Rädle Klinik für Innere Medizin II, Gastroenterologie, Hepatologie, Endokrinologie, Diabetologie und Ernährungsmedizin Universitätsklinikum des Saarlandes Kirrberger Str., 66424 Homburg/Saar, Germany jochen.raedle@uniklinikum-saarland.de ADDITIONAL TABLE - SEE NEXT PAGE Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 12 MEDICINE ADDITIONAL TABLE Screening methods for assessing the nutritional status of outpatients and inpatients, as well as elderly patients (e81, e82) Screening method Target group/setting MUST Adults Influential variables and assessment Body mass index Malnutrition universal screening Tool General practice Unplanned weight loss in preceding 3–6 months Acute illness with no food intake for more than 5 days Maximum of 6 points: Malnutrition 2 points NRS-2002 Adults Nutritional risk screening Hospital Prescreening with 4 questions Body mass index Weight loss in preceding 3 months Lowered food intake Severity of illness Main screening if one of the prescreening questions answered in the affirmative Impaired nutritional status Severity of illness Age Maximum of 7 points: Nutritional risk 3 points MNA Mini nutritional assessment Old patients Institution for old people Pre-history with 6 questions; Maximum 14 points; Nutritional risk 11 points Appetite Weight loss Mobility Acute illness Psychological situation Body mass index Main history with 12 questions Living situation Drugs Nutritional habits (number of meals, choice of foods, amount of fluids taken in) Self assessment Anthropometric measures (circumference of upper arm, calf) Maximum 30 points; Malnutrition 17 points Dtsch Arztebl 2007; 104(26): A 1914–21 ⏐ www.aerzteblatt.de 13