Avery, D., Hernandez, M., & Hebl, M. (2004). Recruiting diversity

Who’s Watching the Race?

Racial Salience in Recruitment Advertising

1

D EREK R. A VERY2

Saint Joseph’s University

M ORELA H ERNANDEZ AND M ICHELLE R. H EBL

Rice University

A recent finding (Thomas & Wise, 1999) suggested that the race of organizational representatives may be more important to minority applicants than to White applicants. Consequently, this study empirically examines the impact of race in recruitment advertising on applicant attraction. Participants ( N = 194) were recruited in 3 field settings and were exposed to recruitment literature varying the race of a depicted organizational representative. Results indicate that Black and Hispanic participants were more attracted when minority representatives were depicted; White participants’ reactions were unaffected by representative race. Moreover, the extent to which participants believed themselves to be similar to the representative fully mediated the effect for minority participants.

Several recent findings have demonstrated that racial diversity can be an invaluable asset to organizations. For instance, racial diversity may enhance creativity, add value to the organization in terms of return on equity, and provide a competitive advantage over racially homogeneous firms (McLeod, Lobel, &

Cox, 1996; Richard, 2000). Furthermore, successful management of diversity has been linked with subsequent increases in company stock price (Wright, Ferris,

Hiller, & Kroll, 1995). Clearly, having racially diverse personnel makes good business sense for today’s organizations.

Although prior studies have illustrated the potential value added by employing a diverse workforce, researchers have been far less prolific in demonstrating effective methods of recruiting such employees (Highhouse, Stierwalt,

Bachiochi, Elder, & Fisher, 1999; Perkins, Thomas, & Taylor, 2000; Thomas &

Wise, 1999). Research on minority recruitment is particularly important because an increasing number of women and minorities (nontraditional workers) are

1 An earlier version of this manuscript was presented at the 16th annual conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology in San Diego, California (April 2001). The authors thank David Kravitz, Sharon Matusik, Donald Williams, Scott Philips, Eddie Miranda, and Sarah

Bohn for their invaluable assistance.

2 Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Derek R. Avery, 5600 City Avenue, Philadelphia, PA 19131. E-mail: davery@sju.edu

146

Journal of Applied Social Psychology , 2004, 34 , 1, pp. 146-161.

Copyright © 2004 by V. H. Winston & Son, Inc. All rights reserved.

RACIAL SALIENCE IN RECRUITMENT ADVERTISING 147 entering the workforce and will fuel future labor market growth (Dreyfuss,

1990). In addition, minority applicants appear to be attracted by different factors than are their White applicant counterparts (Thomas & Wise, 1999). It is imperative for corporations to understand these differences to determine optimal methods of attracting diverse applicants.

Perhaps the first contact that a potential applicant has with any prospective employer is via organizational recruitment literature. However, despite a multitude of studies examining the recruitment process (for a recent review, see

Breaugh & Starke, 2000), empirical research on the effects of recruitment literature on potential applicants’ of color has been scarce (Perkins et al., 2000). As a result, recent research has sought to fill this void by examining the effects of advertised human resource practices (Highhouse et al., 1999) and diversity portrayed in recruitment advertisements (Perkins et al., 2000). Despite the promising findings of these efforts, it remains uncertain whether members of various ethnic/racial groups differ with respect to the impressions created by recruitment literature.

Consequently, the present study examines the impact of the race of depicted organizational representatives on organizational attractiveness. Specifically, we assess the moderating role of the applicant’s race, as well as two potential mediators of this prospective interaction. An important contribution of the current study is the consideration of Hispanics, 3 who often have been neglected in research focusing primarily on Black–White differences. Those studies that have included Hispanic respondents suggest that their attitudes often differ significantly from their Black and White counterparts (Bell, Harrison, & McLaughlin,

1997; Citrin, 1996; Kravitz & Platania, 1993; Skerry, 1993), suggesting a need for independent consideration. In the sections that follow, we discuss the theoretical rationale underlying the study and present our hypotheses.

Theoretical Rationale

Research has suggested that race is often used as a proxy for interpersonal similarity (Elsass & Graves, 1997). Individuals tend to perceive members of their own race as more similar to themselves than members of other racial groups.

This perceived similarity in turn heightens attraction to the individual. For instance, Tajfel and Turner (1985) found that in-group members are seen as more attractive than are out-group members because they are perceived as being more

3 We use the term Hispanic rather than Latino in reference to individuals of Latin and South

American descent because it is consistent with the categorization scheme used by the U.S. Bureau of the Census (DeNavas-Walt, Cleveland, & Roemer, 2001). Thus, we feel that Hispanic serves as the most descriptive label for the group whose attitudes we are attempting to examine (for more on ethnic categories and labels, see Phinney, 1996).

148 AVERY ET AL .

similar to the individual. This linkage between similarity and attraction is commonly known as the similarity-attraction paradigm (Byrne, 1961).

Although Byrne (1961) was concerned primarily with attitudinal similarity, subsequent research has extended the findings of the similarity-attraction paradigm to other types of similarity (Perkins et al., 2000; Perry, Kulik, & Zhou,

1999; Tajfel & Turner, 1985; Young, Place, Rinehart, Jury, & Baits, 1997).

For example, the similarity-attraction paradigm has been used as a means of explaining the role of racial similarity in recruitment. Young et al. utilized the similarity-attraction paradigm as their basis for predicting that racially similar pairs (recruiters and applicants) would produce more positive applicant impressions than would racially mismatched pairs. Their data, which examined 451 applicants for teaching positions, supported this hypothesis, thereby suggesting that the similarity-attraction paradigm may prove useful in explaining applicant attraction to organizations.

In addition to the similarity-attraction paradigm, the current research also relies on the notion of market signaling (Spence, 1973, 1974). Although Spence

(1974) developed market signaling to explain employer decision-making processes, it has been extended to explain applicant cognition as well (Rynes, 1991).

For example, Rynes argued that in early stages of the job-search process, applicants know little about any given prospective employer. As a result, they are likely to use peripheral cues (signals) to infer information about unknown organizational characteristics in order to formulate an impression about the firm. This process of using peripheral cues to surmise information about a prospective organization is known as signaling .

Since Rynes’ (1991) work, several studies have yielded support for signaling as an explanation of applicant reactions (e.g., Goltz & Giannantonio, 1995;

Rynes, Bretz, & Gerhart, 1991; Turban & Greening, 1996). For instance, in an extensive interview process, Rynes et al. found that applicants used recruitment experiences (i.e., recruiter competence, gender composition of interview panels, recruitment delays) to infer unknown information about the organization. Similarly, participants who viewed a “friendly” recruiter were more likely to make positive inferences about unfamiliar organizational characteristics (Goltz &

Giannantonio, 1995).

However, researchers using a signaling approach have tended to oversimplify the applicant attraction process. According to Highhouse and Hoffman (2001), focusing merely on the signals sent by organizational cues has led researchers to

“ignore the role of the job seeker as receiver of those signals” (p. 39). This omission led Highhouse and Hoffman to introduce their own process model of signaling that includes three key elements: cues, signals, and heuristics.

Cues are observable organizational features that are exposed to potential job seekers during the recruitment process.

Signals refer to the messages that organizations intend for cues to convey to prospective applicants.

Heuristics are the rules of

RACIAL SALIENCE IN RECRUITMENT ADVERTISING 149 thumb that job seekers use to interpret recruitment cues. Although companies can manipulate the cues that they present to project certain signals, applicants’ heuristics are the factor most likely to determine the effectiveness of organizational recruitment efforts.

The current research integrates the similarity-attraction hypothesis and this new process model of signaling to further explicate applicant behavior. One probable heuristic involves applicants using cues they observe in recruitment literature (e.g., the race of an organizational representative) to surmise the likelihood that individuals employed at the prospective organization are similar to themselves. This similarity may then form the basis of their attraction (or lack thereof) to the organization. Thus, applicants may interpret the race of organizational representatives in recruitment advertisements using a “racial similarity is more attractive” heuristic.

Effects of Race

The notion that the race of organizational representatives might impact applicant behavior is not novel. In fact, Wyse (1972) conducted the first known study examining the effects of recruiter race. His findings revealed effects for Black participants, but not White participants. Specifically, Black participants responded more positively to recruiters of their own race and, thus, were more likely to pursue a job with the company. Conversely, the race of the recruiter appeared to be of little or no importance to White applicants.

Although few would dispute that racial attitudes and demographic composition in the United States have changed significantly in the 30 years since Wyse’s

(1972) research, surprisingly few studies have since replicated or extended this finding. In fact, we found only three studies that focused on the role of race in recruitment literature during the past decade (Perkins et al., 2000; Thomas &

Wise, 1999; Young et al., 1997). Of these studies, the aforementioned Young et al. study reported that organizational attraction was greater when the recruiter was of the same race as the potential applicant. Similar results were reported by

Thomas and Wise, who assessed master of business administration (MBA) students and found that minority applicants viewed diversity characteristics as being more important than did nonminorities. This led them to claim that the presentation of the racial diversity of an organization may be more salient to minorities.

Most recently, Perkins et al. (2000) conducted a study similar to the current research consisting of 196 Black and White students and examined the effect of various levels of racial diversity portrayed in a recruitment advertisement on potential applicants’ attraction to the firm. They included four levels of racial diversity in the ads that were shown to the participants: 100% White; 90% White/

10% Black; 70% White/30% Black; and 50% White/50% Black models. Their results indicated a positive linear relationship between the percentage of Blacks

150 AVERY ET AL .

portrayed and organizational attraction, perceived compatibility, and organizational image for Black respondents. There was no effect of racial ad composition for White respondents.

Although Perkins et al.’s (2000) research made a needed contribution to our understanding of the role of race in recruitment literature, it leaves several important questions unanswered. For example, their research only examined Black and

White participants, and it is uncertain whether the in-group preference they reported for Blacks would generalize to members of other racial minority groups.

Another question arises as a function of the stimulus utilized by Perkins et al.

Although it is often the case that corporate recruitment literature contains pictures of a number of employees, many ads depict only a few or one representative. Perkins et al.’s findings are difficult to generalize to such ads. An ad containing 1 White representative and 0 Black representatives is likely to garner a different reaction from a minority applicant than one containing 10 White representatives and 0 Black representatives. Finally, Perkins et al. failed to offer any potential explanation for the mechanism underlying the effects that they reported.

This marks a common shortcoming of organizational race research in that potential mediators of racial effects are often ignored (Lawrence, 1997; Nkomo, 1992).

The current study seeks to further explicate these questions. Based on prior research findings regarding the similarity-attraction paradigm, it is anticipated that applicants will regard an organization as most attractive when the organizational representative depicted in recruitment literature is a member of their race.

However, past research (e.g., Perkins et al., 2000; Thomas & Wise, 1999) has suggested that White applicants may not exhibit this effect. Perhaps race is less salient to them, as they are regularly the numerical majority (Davis & Burnstein,

1981). Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1 . Black applicants will be most attracted to an organization when the organizational representative is Black.

Hypothesis 2 . Hispanic applicants will be most attracted to an organization when the organizational representative is Hispanic.

Hypothesis 3 . White applicant attraction to an organization will be unaffected by the race of the organizational representative.

The current study also examines a potential underlying mechanism for the effects proposed in Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. The similarity-attraction paradigm suggests that minority applicants will perceive a greater degree of similarity to organizational representatives when they are of the same race. Increases in perceived similarity should correspond with greater attraction to the organization because applicants tend to generalize characteristics of organizational representatives to the organization in general (Goltz & Giannantonio, 1995). This linkage is

RACIAL SALIENCE IN RECRUITMENT ADVERTISING 151 conceptually similar to the attraction phase of the attraction–selection–attrition

(ASA) model, which also proposes that similarity begets attraction (Schneider,

1987).

Furthermore, organizations may use the race of the representatives that they display to signal the value that they place on diversity (Thomas & Wise, 1999). If a minority is depicted, diverse applicants may use a heuristic to conclude that the organization is minority-friendly and therefore be more attracted to it. Following this logic, it is expected that perceived participant–representative similarity and perceived organizational value of diversity will intervene in the relationships specified in Hypotheses 1 and 2. We should note that by testing for mediation, the current research adheres to the suggestion that future organizational research on race should explore the mechanisms underlying its effects (Lawrence, 1997;

Nkomo, 1992).

Hypothesis 4 . Perceived participant–representative similarity will mediate the relationship between representative race and organizational attractiveness.

Hypothesis 5 . Perceived organizational value of diversity will mediate the relationship between representative race and organizational attractiveness.

Method

Participants

A total of 194 participants (104 male, 90 female) voluntarily took part in this study. Participants were a racially diverse group: 30.4% Black (28 male, 31 female), 26.8% Hispanic (31 male, 21 female), and 42.8% White (45 male, 38 female). To maximize the external validity of the results, data were collected from MBA students via the Internet ( N = 31), adults at a local airport ( N = 67), and students (undergraduate and graduate) at a southern university ( N = 96).

To ensure that the data collected from the three sites were comparable, independent analyses were performed for each location. Because the results were consistent across the samples and no significant statistical differences were detected, the data were combined for all analyses. The average participant was 29 years old with a bachelor’s degree, 8.75 years of work experience, and an annual household income between $45,000 and $65,000.

Experimental Design

This study was a 3 3 (Representative Race: Black, Hispanic, or White

Applicant Race: Black, Hispanic, or White) between-subjects experimental

152 AVERY ET AL .

design. Each participant viewed a recruitment brochure for a firm that contained the same company description with only the race of the representative varying across conditions. Each brochure depicted only one organizational representative to enhance our understanding of applicant reactions to this common type of recruitment advertisement. This design aims to supplement the findings of previous research examining ads portraying groups of representatives (Perkins et al.,

2000).

Stimuli

A total of 12 recruitment advertisements for a fictitious corporation (Drilane

Consulting) were developed based on existing advertisements found in popular press and business publications. All advertisements had the identical company name and descriptive information.

To avoid the possibility of confounds (job titles, geographic location, type of organization), the text was purposely developed as a vague description of a company with no specific details about the job itself. Perkins et al. (2000) noted that

“Advertisements such as these, which lack detailed descriptive information, still retain mundane realism, as evidenced by the number of similarly vague recruitment brochures found in many popular business magazines and on the Internet”

(p. 243).

The stimulus material varied by the race of the representatives pictured. To design the study’s advertisement stimuli, six male and six female headshots were morphed electronically onto two bodies (one male and one female, respectively) dressed in business attire. Of the 12 stimuli utilized in this experiment, 4 were

Black (2 males, 2 females), 4 were Hispanic (2 males, 2 females), and 4 were

White (2 males, 2 females). It is important to note that this use of multiple stimuli for each race is likely to bolster construct validity (Wells & Windschitl, 1999).

Moreover, pretesting revealed that the individuals depicted in the photos did not appear to have been altered, were equivalent in attractiveness, and were easily racially identifiable. Thus, although we cannot rule out the possibility that these stimuli failed to represent the three races adequately, the use of four racially unambiguous sample stimuli for each race makes this less likely (Wells &

Windschitl, 1999).

Measures

For all of these items, participants responded on 7-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 ( strongly disagree ) to 7 ( strongly agree ).

Organizational attractiveness . Participants’ perceptions of organizational attractiveness were measured using four items ( = .86) similar to those used in previous studies (e.g., Turban & Keon, 1993). A sample item is “ I would be interested in working for Drilane Consulting.”

RACIAL SALIENCE IN RECRUITMENT ADVERTISING 153

Perceived participant–representative similarity.

Four items designed by the researchers were used to measure participants’ perceptions of similarity ( =

.81). A sample item is “The recruiter and I are likely very similar.” In the early stages of this study, this variable was not included in the questionnaire. As a result, this variable was not available for half of the respondents.

Perceived organizational value of diversity.

Participants’ perceptions regarding how much the organization valued workforce diversity were assessed using four items developed by the researchers ( = .75). A sample item is “Clearly, diversity is not important to Drilane” (reverse scored).

Demographic variables.

Participants were asked to indicate their gender, age, economic status, educational level, and job experience, which were collected to test and control for their effects in the statistical analyses. Tests of the homogeneity of regression assumption were conducted, and no statistically significant interactions were detected between the demographics and the independent variables. Thus, the effects of the independent variables were independent of these demographics, and they were included as covariates in the analyses. For economic status and educational level, responses were rated on 5-point ordinal scales. Missing data were imputed using the series mean, an approach that is appropriate, given that these variables were used solely as covariates (Little &

Rubin, 1987).

Procedure

Although participants were solicited from three different sites, the administration of the study was consistent across all three. All participants were presented with a company brochure containing typical recruitment literature information

(e.g., organizational goals) about a fictional company. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the three experimental conditions involving a Black,

Hispanic, or White representative. As part of the cover story, participants were told that the company was an “up-and-coming consulting firm planning geographical expansion.” Furthermore, they were led to believe that the survey they were completing was a marketing survey designed to help the company calibrate its organizational recruitment image before expanding. After viewing the company brochure, participants were instructed to complete the measures immediately. After participants completed and returned the measures, they were thanked for their participation.

Results

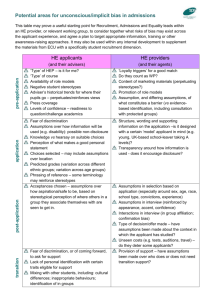

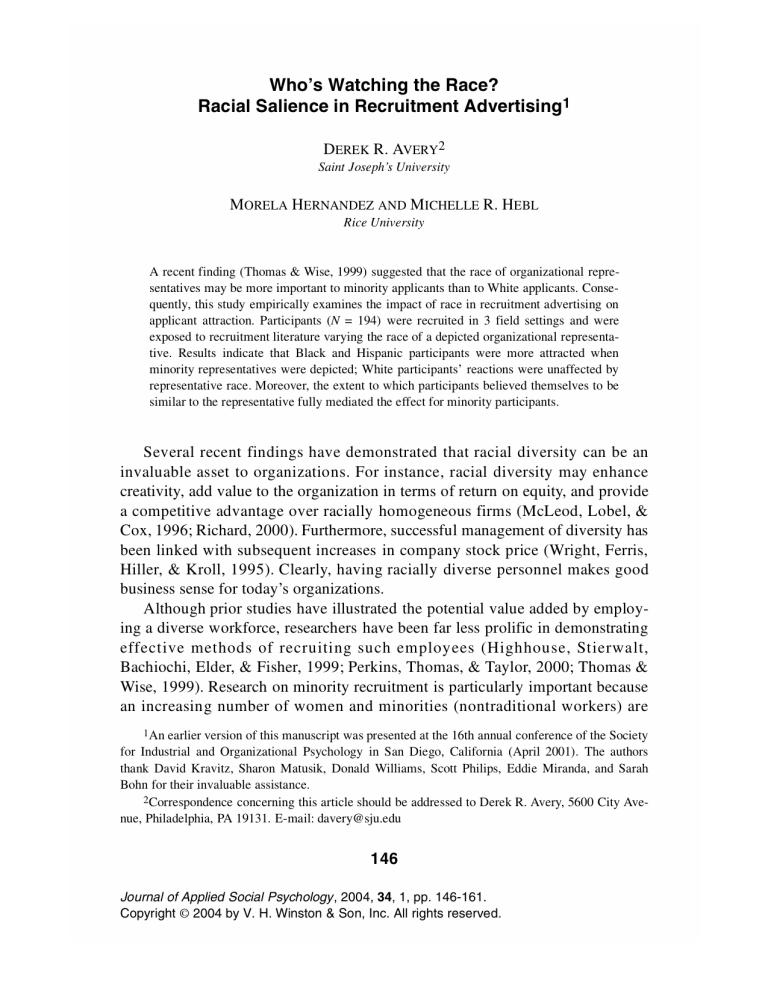

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for all of the measures used in the study are presented in Table 1. The first two hypotheses proposed that Black and Hispanic applicants would be most attracted when a representative of their

154 AVERY ET AL .

RACIAL SALIENCE IN RECRUITMENT ADVERTISING 155

Figure 1 . The interaction between participant and representative race on organizational attractiveness.

own race was depicted. These hypotheses were tested using ANCOVA. Entering the demographic variables (gender, age, income, educational level, and experience) as covariates, the effects of recruiter race, applicant race, and the interaction between the two on organizational attractiveness was tested. As expected, the interaction between applicant race and representative race was statistically significant, F (4, 180) = 4.88, p < .001, 2 = .10. Figure 1 presents a graphic illustration of the interaction.

To test the individual components of Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, we independently examined how the participants of each racial group reacted to the various recruiters. Black applicants viewed the company as more attractive when Black representatives (as opposed to White representatives) were used ( M = 17.60 vs.

11.77), t (34) = 3.12, p < .01. Contrary to Hypothesis 1, Black participants rated the organization as equally attractive when presented with Black and Hispanic representatives ( M = 17.61 vs. 17.61), t (43) = 0.00, ns . As a result, Hypothesis 1 received only partial support.

Hypothesis 2 was also partially supported. Hispanic applicants viewed the company as significantly more attractive when a Hispanic representative was depicted than when a White representative was shown ( M = 19.46 vs. 15.50), t (29) = 2.10, p < .05. Unexpectedly, Hispanic applicants did not view the organization differently when the representative was Black or Hispanic ( M = 17.14 vs.

19.46), t (32) = -1.30, ns .

Hypothesis 3 predicted a null effect of recruiter race for White participants.

This hypothesis was supported, as White respondents failed to exhibit a significant

156 AVERY ET AL .

preference for organizations as a function of representative race, F (2, 80) = 1.38, p = .26, 2 = .03. Specifically, the organization was perceived as equally attractive when Black, Hispanic, and White representatives were presented ( M = 12.76,

13.65, and 15.13, respectively). However, the means indicate that the White respondents exhibited a nonsignificant pattern of in-group favoritism.

Hypotheses 4 and 5 predicted that the interactive effects of participant and representative race predicted in the previous hypotheses would be mediated by perceived participant–representative similarity (Hypothesis 4) and perceived organizational value of diversity (Hypothesis 5). A test for mediated moderation involves three steps (Baron & Kenny, 1986). First, the hypothesized interaction must exert a statistically significant effect on the dependent variable. Second, the hypothesized interaction must exert a statistically significant effect on the mediator. Finally, the effect of the interaction on the dependent variable must be attenuated when the effect of mediator is controlled.

In the present study, the effect of the Participant Race Representative Race interaction on organizational attractiveness was statistically significant. The effect of the interaction was also statistically significant in predicting perceived participant–representative similarity, F (4, 82) = 2.48, p < .05, 2 = .11. However, there was no significant effect of the interaction on perceived organizational value of diversity. Consequently, Hypothesis 5 was not supported. As a test of the final requirement for mediated moderation, the effect of the Participant Race

Representative Race interaction on organizational attractiveness was attenuated after controlling the effect of perceived participant–representative similarity,

F (4, 81) = 1.22, ns , 2 = .06. Therefore, perceived participant–representative similarity fully mediated the interactive effect of participant and representative race on attraction, and Hypothesis 4 was supported.

To further explore this mediated moderation, we examined the effects of perceived participant–representative similarity separately for each racial group. The main effect of representative race on organizational attractiveness was significant for Black applicants, F (2, 55) = 6.23, p < .01, 2 = .18, but only marginal for

Hispanic participants, F (2, 51) = 2.35, p = .10, 2 = .09, suggesting that the preference for minority representatives exhibited by Black and Hispanic participants was stronger for Blacks. There was no significant racial preference for White participants, F (2, 80) = 1.39, ns , 2 = .03.

Black and Hispanic participants also exhibited a statistically significant effect of perceived participant–representative similarity, F (2, 32) = 4.60, p < .05, 2 =

.22; and F (2, 33) = 5.33, p < .01, 2 = .25, respectively. Further, the racial preference effect was attenuated for both Black, F (2, 31) = 1.75, ns , 2 = .10; and

Hispanic participants, F (1, 32) = .12, ns , 2 = .01, after controlling for their perceptions of participant–representative similarity. These analyses further suggest that mediated moderation occurred, thereby contributing additional support for

Hypothesis 4.

RACIAL SALIENCE IN RECRUITMENT ADVERTISING 157

Discussion

Minorities appear to place greater emphasis on the race of the representative in recruitment literature than do White applicants when evaluating potential employers, thereby reinforcing the results of Thomas and Wise (1999). The results of this study have implications for organizations, such that organizations may be able to attract more Black and Hispanic applicants by portraying minority representatives in their media materials. Furthermore, the use of minority representatives appears to have no (or at least very small) deleterious effects on the attraction of White applicants, making it a win–win scenario for firms seeking racial/ethnic diversity. This finding reinforces Perkins et al.’s (2000) claim that

“portraying diversity in one’s advertisements may assist in recruiting minority job seekers but have little effect on non-minorities” (p. 248). Although race does not appear to be salient to White applicants, we should note that different results might be obtained if they were given a choice between an organization with a

Black and an organization with a White representative. It is also likely that race would be more salient to a White applicant if presented with a scenario wherein

White representatives are the numerical minority in a group.

By examining the mediating role of perceived participant–representative similarity, this study went beyond merely detecting an effect of race to explain the effect. Too often race researchers fail to extend the premise of their research to determine the mechanism through which race influences behavior in organizations (Lawrence, 1997). In the present study, Black and Hispanic applicants preferred organizations with minority recruiters because they perceived a greater degree of similarity with these representatives. Our results not only imply that representative race is important in attracting minorities, but also specify why it is important. Moreover, the “racial similarity is more attractive” heuristic was supported for minority job seekers.

One limitation of the present research is that complete data were not available for the perceived applicant–representative similarity variable. However, the pattern of results for the participants who completed the similarity measure is highly consistent with that reported, and there is no reason to anticipate that those with complete data systematically differed from those who did not have complete data. The study also relied on self-reported data, making it potentially vulnerable to social desirability. However, the majority of participants were unaware of the study’s purpose, even after completion of the measures, making it unlikely that social desirability influenced the results. Furthermore, previous research has demonstrated that self-reported perceptions of organizational attraction correspond well with subsequent job-choice decisions (Turban, Campion, & Eyring,

1995).

Future research might examine the other factors cited by Thomas and Wise

(1999) that are differentially important to Whites and minorities when evaluating

158 AVERY ET AL .

prospective employers. These include organizational diversity factors such as diversity management, as well as recruiter factors such as personableness or competency. Subsequent studies also might consider examining other ethnic groups, such as Asian Americans (who unlike Blacks and Hispanics are often products of more affluent backgrounds 4 ), to determine if they exhibit a similar bias toward racial minority representatives. It also would be interesting to see if the results reported here change as the individual becomes more familiar with aspects of the job and organization that were held constant in our experimental design.

An unexpected finding was that Black and Hispanic participants did not differentiate between the brochures depicting Black representatives and those depicting Hispanic representatives. This suggests that minorities may view the race of organizational representatives in terms of minority status (Phinney, 1996).

Therefore, the fact that a representative is also a member of a minority group

(even if it is not the applicant’s group) may be sufficient for minority viewers to assume some degree of similarity with the representative. Further research is necessary to determine to what extent this holds true regarding other racial minority groups, as well as to examine other inferences that minorities may draw from pictures in recruitment literature. Minorities in the present study did not use the representative’s race to infer the organizations’ stance on diversity. Perhaps a formal statement might impact minorities’ assessment of the firms’ level of racial tolerance and inclusiveness.

Despite its limitations, this study has several strengths. The sample contained students as well as gainfully employed adults. Thus, the results are likely to generalize to a broad range of occupations. Furthermore, an important distinction from previous research is that it included Black and Hispanic participants without collapsing across minority groups, thereby allowing for independent comparisons of different ethnic groups. Many studies tend to treat minorities as a homogeneous group while failing to consider that racial/ethnic groups differ with respect to their attitudes and values (Cox, Lobel, & McLeod, 1991). Specifically, very little work has examined Hispanic attitudes as they relate to the workplace.

Finally, our use of multiple stimuli for each race suggests that inferences drawn from the results are likely to be valid (Wells & Windschitl, 1999).

On a practical note, it is important to consider the findings discussed here in light of the realistic job preview literature (for a recent review, see Breaugh &

Starke, 2000). If minorities are more attracted to companies portraying minorities in their literature, this is presumably because they believe they will find employees who are racially similar to them within the organization. If this is not the case,

4 This statement is reflective of the findings of the 2000 U.S. Census (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2001).

De-Navas et al.’s findings revealed that the median household income of Whites, Hispanics, Blacks, and Asian/Pacific Islanders was $45,904; $33,447; $30,439; and $55,521, respectively.

RACIAL SALIENCE IN RECRUITMENT ADVERTISING 159 retaining minorities may become significantly more difficult than attracting them. Nevertheless, this study provides an important step in determining the optimal methods for their recruitment.

References

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 51 , 1173-1182.

Bell, M. P., Harrison, D. A., & McLaughlin, M. E. (1997). Asian American attitudes toward affirmative action in employment: Implications for the model minority myth.

Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , 33 , 356-377.

Breaugh, J. A., & Starke, M. (2000). Research on employee recruitment: So many studies, so many remaining questions.

Journal of Management , 26 ,

405-434.

Byrne, D. (1961). Interpersonal attraction and attitude similarity.

Journal of

Abnormal and Social Psychology , 62 , 713-715.

Citrin, J. (1996). Affirmative action in the people’s court.

The Public Interest ,

122 , 39-48.

Cox, T. H., Lobel, S. A., & McLeod, P. (1991). Effects of ethnic group cultural differences on cooperative and competitive behavior on a group task.

Academy of Management Journal , 34 , 827-847.

Davis, L., & Burnstein, E. (1981). Preference for racial composition of groups.

Journal of Psychology , 109 , 293-301.

DeNavas-Walt, C., Cleveland, R. W., & Roemer, M. I. (2001, September).

Money income in the United States: 2000. Current population reports . Retrieved

October 11, 2001, from http://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/p60-213.pdf

Dreyfuss, J. (1990, April 23). Get ready for the new work force . Fortune ,

163-178.

Elsass, P. M., & Graves, L. M. (1997). Demographic diversity in decisionmaking groups: The experiences of women and people of color.

Academy of

Management Review , 22 , 946-973.

Goltz, S. M., & Giannantonio, C. M. (1995). Recruiter friendliness and attraction to the job: The mediating role of inferences about the organization.

Journal of

Vocational Behavior , 46 , 109-118.

Highhouse, S., & Hoffman, J. R. (2001). Organizational attraction and job choice. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 16, pp. 37-64). New York,

NY: Wiley & Sons.

Highhouse, S., Stierwalt, S. L., Bachiochi, P., Elder, A. E., & Fisher, G. (1999).

Effects of advertised human resource management practices on attraction of

African American applicants.

Personnel Psychology , 52 , 425-442.

160 AVERY ET AL .

Kravitz, D. A., & Platania, J. (1993). Attitudes and beliefs about affirmative action: Effects of target and of respondent sex and ethnicity.

Journal of

Applied Psychology , 78 , 928-938.

Lawrence, B. S. (1997). The black box of organizational demography.

Organizational Science , 8 , 1-22.

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (1987).

Statistical analysis with missing data .

New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

McLeod, P. L., Lobel, S. A., & Cox, T. H. (1996). Ethnic diversity and creativity in small groups.

Small Group Research , 27 , 248-264.

Nkomo, S. M. (1992). The emperor has no clothes: Rewriting “race in organizations.” Academy of Management Review , 17 , 487-513.

Perkins, L. A., Thomas, K. M., & Taylor, G. A. (2000). Advertising and recruitment: Marketing to minorities.

Psychology and Marketing , 17 , 235-255.

Perry, E. L., Kulik, C. T., & Zhou, J. (1999). A closer look at the effects of subordinate–supervisor age differences.

Journal of Organizational Behavior ,

20 , 341-357.

Phinney, J. S. (1996). When we talk about American ethnic groups, what do we mean?

American Psychologist , 51 , 918-927.

Richard, O. C. (2000). Racial diversity, business strategy, and firm performance:

A resource-based view.

Academy of Management Journal , 43 , 164-177.

Rynes, S. L. (1991). Recruitment, job choice, and post-hire consequences: A call for new research directions. In M. D. Dunnete & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organization psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 399-444).

Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Rynes, S. L., Bretz, R. D., & Gerhart, B. (1991). The importance of recruitment in job choice: A different way of looking.

Personnel Psychology , 44 , 487-521.

Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place.

Personnel Psychology , 40 ,

437-453.

Skerry, P. (1993).

Mexican Americans: The ambivalent minority . New York, NY:

The Free Press.

Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling.

Quarterly Journal of Economics , 87 ,

355-374.

Spence, M. (1974).

Market signaling . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1985). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations

(2nd ed., pp. 7-24). Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall.

Thomas, K. M., & Wise, P. G. (1999). Organizational attractiveness and individual differences: Are diverse applicants attracted by different factors?

Journal of Business and Psychology , 13 , 375-390.

Turban, D. B., Campion, J. E., & Eyring, A. R. (1995). Factors related to job acceptance decisions of college recruits.

Journal of Organizational Behavior ,

47 , 193-213.

RACIAL SALIENCE IN RECRUITMENT ADVERTISING 161

Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1996). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees.

Academy of Management Journal , 40 , 658-672.

Turban, D. B., & Keon, T. L. (1993). Organizational attractiveness: An interactionist perspective.

Journal of Applied Psychology , 78 , 184-193.

Wells, G. L., & Windschitl, P. D. (1999). Stimulus sampling and social psychological experimentation.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 25 ,

1115-1125.

Wright, P., Ferris, S. P., Hiller, J. S., & Kroll, M. (1995). Competitiveness through management of diversity: Effects on stock price valuation.

Academy of Management Journal , 38 , 272-287.

Wyse, R. E. (1972). Attitudes of selected Black and White college business administration seniors toward recruiters and the recruiting process (Doctoral dissertation, Ohio State University).

Dissertation Abstracts International , 33 ,

1269A-1270A.

Young, I. P., Place, A. W., Rinehart, J. S., Jury, J. C., & Baits, D. F. (1997).

Teacher recruitment: A test of the similarity–attraction hypothesis for race and sex.

Educational Administration Quarterly , 33 , 86-106.