Lesson 4 – Debates - Classroom Law Project

advertisement

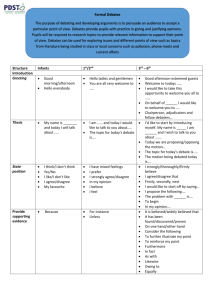

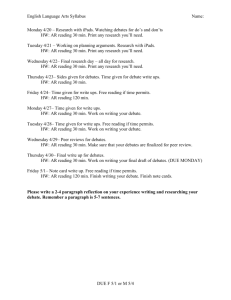

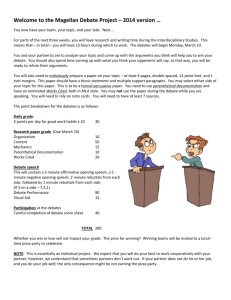

CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Youth Summit 2008 LESSON 4 What should I watch for in the debates? Objectives Students will develop criteria for evaluating the debate performance of the candidates and observe media coverage of the debates. Handouts (4-1) Debate Schedule; (4-2) Debate Checklist; (4-3) Debate Scoresheet; (4-3) Scoring Debaters Backgrounder Understanding Debates: A Viewer’s Guide; Polling Resources; Presidential Debates Matter. A. Daily warm-up Elicit student reaction: What campaign issues are being discussed? What issues do you want to hear discussion about? Or, since we last met, what have you heard (read or seen) about the election? B. What is a debate? A formal, oral confrontation between two individuals, teams, or groups who present arguments to support opposing sides of a question, generally according to a set form or procedure. Source : www.britannica.com. C. When are the Presidential Debates? Mark your calendars! (See Handout 4-1 for more detail.) September 26 October 7 October 2 – Vice Presidential debate October 15 Consider the moderators. What are their qualifications? Do they make a difference? What about the format of the debates; does it make a difference? What is the purpose of these features of the Presidential Debates? Think about time limits, seating and other debate format decisions. How do they impact the debate? D. Vocabulary Affirmative – approving or supporting Negative – denying or opposing Rebut – to present opposing evidence or arguments Refute – to prove to be false Resolution – the purpose of the resolution is to define and limit the topic or debate And, to track the debates, consider the arguments in three parts (A-R-E): Assertion Reasoning Evidence Source: http://teachingdebate.typepad.com/teaching_debate/2007/08/a-r-e-tracking.html . E. How should I watch the debates? Teachers: see Handout 4-1 for a schedule of the debates. Strategy below works best when showing taped debate excerpts in class; watching debates could also be a 1 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Youth Summit 2008 homework assignment. The one-page backgrounder, Understanding Debates: A Viewer's Guide, is a helpful resource for both teachers and students. Ask, "what is a debate about?" Suggest that it should be a demonstration of one's knowledge NOT showing what others do not know; a marketplace of ideas NOT one idea; expressing opinions NOT putting others down. Debate watchers are urged not to look for the winner but rather who will make a better president. Prepare students for debate watching by reviewing Debate Checklist, Handout 4-2, as a class. For a tool to use while watching the debate itself, refer to Handouts 4-3 and 4-4. They provide options for helping students be wise debate watchers. Review them; choose one or both viewing tools to use with your students. One strategy is to ask students to look for different things during the debate. For example, some students may be asked to focus upon issues (how much did the candidates seem to know?), others on style (how well did the candidates communicate?), and others consistency (how well did the candidates match their ads?), and so on. After watching, students should reflect individually before engaging in small group discussion on their respective topic areas. Finally, the small groups should present their views with the whole class. E. Do the debates make a difference? After watching a debate, check polling sites to see if the debate seems to make a difference. Pollster John Zogby believes that the presidential debates will determine the election, (http://presidentialdebateblog.blogspot.com/2008/09/zogby-presidentialdebate-prediction.html). Backgrounder Polling Resources provides more polling websites, basic background and an activity; see also backgrounder, “Why Debates Matter.” F. Extended Activities Chain-debate. This is an effective strategy to do a quick mini-debate in your class. Divide the class in two groups of 15 (assuming a 30 student class). In each group, do a quick brainstorm on the topic, “presidential debates influence voters.” In a chain debate, each student will make a very short statement (1-2 sentences). Begin with five students making one statement (or assertion) each, then five students give rebuttals, and finish with five summaries. Homework / Journal Entry • As a result of watching the debate, I think that Senator (McCain or Obama) would be the best choice for president because . • Something that surprised me about the debates was • An informed voter should be a debate watcher. Why or why not? • If I were the moderator of the debates (or if I were John McCain or Barack Obama; Sarah Palin or Joe Biden), I would have . 2 because . CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Youth Summit 2008 Additional resources for teachers For a reminder of how presidential debates have evolved to take the important place they do today in elections, see this from Univ. of Mississippi, site of this year’s first debate: … news.olemiss.edu/index.php/Ole-Miss-News/DebateNews/1960debate.html. Constitutional Rights Foundation’s Election Central is a treasure trove of online resources, http://www.crf-usa.org/election_central/election_links.htm#presidential. Commission on Presidential Debates. Non-profit group that has sponsored the presidential and vice-presidential debates since 1988. Current and past information, including transcripts, www.debates.org/. New York Times Topics: Presidential Debates. Archive of news stories and transcripts of the presidential debates, nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/p/presidential_debates/index.html. CNN: Debates History. Summaries of all the presidential debates with links to further information, www.cnn.com/ELECTION/2000/debates/history/. Museum of Broadcast Communication: Great Debate & Beyond. A history of televised presidential debates from 1960–2000, www.museum.tv/debateweb/html/index.htm. Myspace and Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD) launched Mydebates.org empowering users to watch debates via live webstream and access candidate responses on demand, www.myspace.com/mydebates. About campaign financing: This is an extremely complex area and it is an important part of presidential campaigning. For a lesson that explores this topic, teachers may wish to see: CT-N (Connecticut Network State Civics Toolbox) Campaign Finance Unit developed and edited by Victor W. Geraci, Ph.D. and Paul Petterson, Ph.D., www.ctn.state.ct.us/civics/campaign_finance.asp. About polling: this, too is a complex and important part of the campaign. See Backgrounder for polling resources. 3 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Youth Summit 2008 Handout 4-1 Debate Schedule Friday, September 26 – University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS First presidential debate. Focus on domestic policy. Debate will be ninety minutes in length and start at 6:00 p.m. Pacific Time. Moderator: Jim Lehrer, Executive Editor and Anchor, The NewsHour, PBS. Thursday, October 2 – Washington University in St. Louis, MO Vice presidential debate. Debate will be ninety minutes in length and start at 6:00 p.m. Pacific Time. Moderator: Gwen Ifill, Senior Correspondent, The NewsHour, and Moderator and Managing Editor, Washington Week, PBS. Tuesday, October 7 – Belmont University, Nashville, TN Second presidential debate. Town meeting format will include any issues raised by members of that audience, and the vice presidential debate will include domestic and foreign policy. Moderator: Tom Brokaw, Special Correspondent, NBC News. Wednesday, October 15 – Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY Third presidential debate. Focus on foreign policy. Debate will be ninety minutes in length and start at 6:00 p.m. Pacific Time. Moderator: Bob Schieffer, CBS News Chief Washington Correspondent, and Host, Face the Nation. All debates will be ninety minutes in length and start at 6:00 p.m. Pacific Time. 4 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Youth Summit 2008 Handout 4-2 Debate Checklist Before the Debate Make your own checklist. • It may focus upon issues (how much did the candidates seem to know?), or on style (how well did the candidates communicate?), or on consistency (how well did the candidates match their ads?), or other topics. • Consider also things like: vocabulary choice, personal qualities, knowledge of current events/world leaders, etc. • What was a memorable moment – or what will be in the headlines tomorrow? After the Debate Did the debate influence your attitudes about the issues or the candidates? If so, how? Were there issues of interest not discussed during the debate? Discuss. Were there issues raised that you considered irrelevant or unimportant? What were they? What did you learn about the candidates or issues that you did not know before the debate? Possible additional questions for the second, third or vice presidential debates: What did you learn from this debate that you did not learn from the previous debate(s)? How, if at all, did the press coverage of the previous debate(s) influence your attitudes about the candidates or the issues in this debate? What did you learn from the vice presidential debate that was different from the presidential debate? 5 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Name: Campaign 2008 Period: Examples Debate Score Sheet Addresses issues Always addresses topic Support with facts Uses facts that support topic Persuasiveness Arguments clear and convincing Organization Easy to follow The moderator Asks good questions The moderator Youth Summit 2008 Scoring 1 is low 5 is high Handout 4-3 Debate Scoresheet Date: Candidate One: Name Candidate Two: Name ------------------------------- ------------------------------ Makes sure rules are enforced Your own criteria What you are looking for Based on your ratings, which candidate was most effective? Why? CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Youth Summit 2008 Handout 4-4 Scoring Debaters Two methods for viewing a debate may be used together in one class or separately. To use both, divide the class in half; one half uses the first scoring tool and the other uses the second. Student self-selection may be good – this allows math-minded students to gravitate to the second choice. Teachers may use a taped debate or assign debate watching for homework. Students will watch and score based on a self-created checklist (or Handout 4-3) or on an A-R-E assessment (below). Discuss findings as a class. I. Score candidates Create your own debate score sheet. (Alternatively, use Handout 4-3) List what you will watch for; examples may include: length of answers public speaking skills respectful and polite confidence looking like a leader “presidential” humor dressed for success reasoning role of moderator evidence and more………. rebuttal most interesting question II. Score A-R-E – Assertion, Reasoning, Evidence This strategy uses math! Listen to every question and keep score of the candidates’ responses. Candidates get one point when they made an assertion, two points when they showed reasoning, and three points when they supported with evidence. Give them an overall score - how many points they received out of a possible number. Example: here's how a student rated one of the primary debates, in alphabetical order: • Biden: 12 responses, 100% assertions, 91.6% reasoning, 41.6% evidence, 2.583 average, SCORE: 86.1% • Clinton: 15 responses, 100% assertions, 80% reasoning, 46.6% evidence, 2.6 average, SCORE: 86.6% • Dodd: 12 responses, 100% assertions, 83.3% reasoning, 25% evidence, 2.416 average, SCORE: 80.5% • Edwards: 15 responses, 100% assertions, 73.3% reasoning, 46.6% evidence, 2.8 average, SCORE: 93.3% • Gravel: 10 responses, 100% assertions, 90% reasoning, 40% evidence, 2.6 average, SCORE: 86.6% • Kucinich: 10 responses, 100% assertions, 90% reasoning, 50% evidence, 2.8 average, SCORE: 93.3% • Obama: 20 responses, 100% assertions, 90% reasoning, 60% evidence, 2.7 average, SCORE: 90% • Richardson: 13 responses, 100% assertions, 84.6% reasoning, 53.8% evidence, 2.461 average, SCORE: 82.05%. This method does not yield a “winner;” it does provide information about how well candidates support their points. For more information on using this strategy, see http://teachingdebate.typepad.com/. 7 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Youth Summit 2008 Backgrounder Polling Resources Sources (just a few of them!) Gallup Organization, www.gallup.com/ Harris Interactive, www.harrisinteractive.com/harris_poll/ Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, www.people-press.org/ Polling Report, www.pollingreport.com/ Zogby International, www.zogby.com/ About Polling Definition: A survey, sometimes called a poll, is a study of what people think or believe about a topic or question. Surveys are usually done by questionnaire, interview, or observation. Public opinion polls are useful in tracing people's views on important social issues. Polls are used to assess people's preferences in political races, and the results are used to predict election results. Surveys are often employed in marketing and advertising research to measure and predict consumer's reaction to products. The key concept to bear in mind when analyzing poll data is that public opinion on a given topic cannot be understood by using only a single poll question asked a single time. It is necessary to measure opinion along several different dimensions, to review attitudes based on a variety of different wordings, to verify findings on the basis of multiple askings, and to pay attention to changes in opinion over time. Vocabulary An excellent glossary was developed by American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAOPR) as part of a comprehensive online journalism polling course . See this site not only for terms but also for many interesting issues connected with public opinion and survey research. http://www.aapor.org/glossaryofpollingterms. Questions to ask about polling • How the choice of polling strategy affects the results? • What can we learn from polls? What can’t we? • Do polls influence voter decision-making? • How much influence do polls have in campaign decisions? • How can we identify “partisan” polls? • What is the significance of “undecided”? • What is the role of “exit” polls? How accurate are they? • Is polling an exact or inexact art? • What skills does it take to be a pollster? (career strand) When polls are wrong: a case study Everyone has seen the photo: a gleeful Harry Truman displaying the newspaper headlined “Dewey Defeats Truman.” For more on the “upset win,” according to the polls, of Harry Truman over Thomas E. Dewey in the 1948 election, see http://www.eagleton.rutgers.edu/e-gov/e-politicalarchive-1948election.htm. More recently, see this article, “Hillary Clinton wins New Hampshire, defying polls,” a pollsters’ nightmare the day after Hilary Clinton’s unexpected win in the New Hampshire primary: www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/us_and_americas/us_elections/article3157498.ece. 1 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Youth Summit 2008 CLASS ACTIVITY Using the handout below, First Things First, conduct a poll in class. Individually, each student will answer the questions then, as a group, tally the results. Was there a shift in priorities? Consider whether would it make a difference if the poll was conducted in person or on the phone; consider the effect of appearance, voice, and gender. What about the order in which the questions are asked or how the question is framed? Other factors? First Things First Making public policy decisions isn't just about choosing the best way of attacking a problem -- you also have to consider which problem should be tackled first. There are lots of things the government could do, and many it should do, but not even the federal government can do everything at once. So priorities have to be set. Here you can work through what you think the next administration should do, and what it should do first. Please indicate whether you think each of these issues is very important, somewhat important, somewhat unimportant, or not important at all: Gay Rights Very Important Somewhat Important Somewhat Unimportant Not Important At All College Costs Very Important Somewhat Important Somewhat Unimportant Not Important At All The Environment Very Important Somewhat Important Somewhat Unimportant Not Important At All Terrorism Very Important Somewhat Important Somewhat Unimportant Not Important At All Health Care Very Important Somewhat Important Somewhat Unimportant Not Important At All Race/ethnicity Very Important Somewhat Important Somewhat Unimportant Not Important At All Jobs and the Economy Very Important Somewhat Important Somewhat Unimportant Not Important At All Immigration Very Important Somewhat Important Somewhat Unimportant Not Important At All Taxes and the Budget Very Important Somewhat Important Somewhat Unimportant Not Important At All Are there other issues that you think are important that aren't listed? If so, list them here. This handout is from Public Agenda, a nonpartisan opinion research organization helping Americans explore and understand critical issues since 1975. www.publicagenda.org/firstchoice2004/firstthings-first.cfm. 2 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Youth Summit 2008 Backgrounder Presidential Debates Matter -- A Guest Post by Professor William Benoit, Tuesday, August 5, 2008 Professor William Benoit is the author of several books on political campaigns, including Communication in Political Campaigns. He also has a webpage on political campaigns. There are limitations on the effects of presidential debates. Some people don’t watch them. Some voters have already made up their minds about how to vote (but even they can learn information to reinforce their opinions – and to use as “ammunition” when discussing the campaign with others). However, there is clear evidence that debates do have significant effects on many voters: Multiple studies of watching debates have documented several important effects. Debates increase viewers’ knowledge of the candidates positions on issues. Watching debates can change which position on an issue voters prefer. Viewing a debate influences which issues are thought to be most important by voters (agenda-setting effect). Debates can create, or change, impressions about the candidates’ character. Viewers can even change their vote choice after watching debates. Although these effects do not occur for all voters, enough voters are influenced for these effects to be statistically significant. Particularly given the fact that presidential elections can be very close, debates are capable of influencing the outcome. Note also that those who watch debates are more likely to vote than those who do not vote, so debates’ potential influence is focused on those whose opinions will matter most on election day. Debates also have other, less obvious effects. Candidates address important issues and are pressed by opponents and questions to take clear stands on these issues. Debates serve as a public record of their campaign promises. Unexpected events can mean that Presidents cannot always follow through on campaign promises, but taking clear positions in debates makes it more difficult for candidates to ignore their campaign promises after election. Furthermore, watching debates – and submitting questions when the format allows that possibility – can enhance citizens’ engagement with politics. Apart from potential effects on citizen’s attitudes toward the candidates, debates can inform voters on many of the important issues of the day. For candidates, they are a significant (and free) opportunity to address millions of voters – between forty and sixty million people watched the three presidential and one vice-presidential debates of 2004. Debates also provide candidates with an opportunity to correct misstatements (accidental or intentional) from opponents. Furthermore, debates are unscripted (although candidates do prepare for them), so unexpected questions or statements from opponents could evoke a more candid response (compared with scripted and rehearsed TV spots). Of course, debates have limitations. As mentioned before, many voters do not watch them. Proliferation of cable and satellite TV, as well as the Internet, makes it easier for people who are not interested in politics to avoid debates (watch something else). Also, much of what is said by the candidates responds to the questions asked of them. Unfortunately, research has established that there is no relationship between which questions (topics) are asked by reporters and which issues are most important to voters. Citizens cannot learn about an issue, or the candidates’ positions on that issue, if the topic is ignored in debates. Still, there is no question that debates have important effects on many voters. Benoit, W. L., Hansen, G. J., & Verser, R. M. (2003). A meta-analysis of the effects of viewing U.S. presidential debates. Communication Monographs, 70, 335-350. Benoit, W. L., Stein, K. A., & Hansen, G. J. (2004). Newspaper coverage of presidential debates. Argumentation and Advocacy, 41, 17-27. Source: http://presidentialdebateblog.blogspot.com/2008/08/presidential-debates-matter-guestpost.html 1 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT Empowering Democracy Youth Summit 2008 Backgrounder Understanding Debates: A Viewer's Guide Voters typically identify candidate debates as the most influential source of information received during a campaign. Because of their importance, this guide describes commonly used debate formats, questioning techniques, and guidelines for viewing a debate. It is designed to be useful in viewing state and local debates as well as presidential. Debates use a variety of formats. Primary debates, featuring candidates from the same party, and local debates traditionally are more freewheeling and incorporate a wide range of formats because of multiple candidates. Since 1992, the general election presidential debates have also featured multiple formats including a town hall meeting with citizen questioners. Most debates impose time limits on answers to ensure that all candidates have equal opportunity to respond. Topics may focus on a wide range of issues or may be on a particular theme such as education or the economy. General election presidential debates usually divide the time between foreign and domestic topics. Candidates may have an opening statement, or a moderator may introduce each candidate and begin questioning immediately. In most debates candidates have closing statements. Questions guide the content of debates. There are three types of questions: initial; follow-up; and cross-examination. Initial questions get the debate started by asking candidates to explain or defend a position or compare it to an opponent's. Many initial questions are hypotheticals in the form of, "What would you do if?" Follow-up questions are directed at a candidate after an answer is given. Their purpose is to probe the original response by asking for elaboration or clarification. Some follow-up questions are on an unrelated topic. Follow-up questions may be asked immediately after an initial response is given or after all candidates have answered the initial question. Crossexamination questions are questions that one candidate addresses to another. A separate time can be set aside for cross-examination questions or they may be included as follow-ups. Questions may be posed to candidates from a variety of sources. A single moderator, usually from the media, or a panel of media representatives or subject experts are the most common questioners. Many debates, especially at the local level, allow for questions from the audience at some point in the debate. The Richmond town hall meeting in 1992 was the first general election presidential debate to involve citizen questioners. http://www.debates.org/pages/dwguide.html 1 © 2004 Commission on Presidential Debates