1 COLLEGE, COURTSHIP, MARRIAGE AND WORLD WAR II

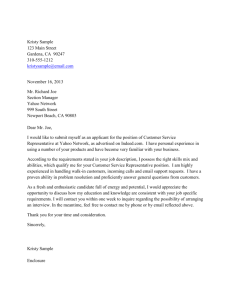

advertisement