Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 1

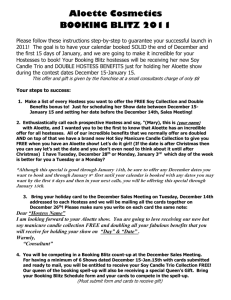

advertisement

Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 1 Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations During the Demise of Hostess Brands, Inc. Holly K. Herndon March 15, 2013 University of Washington LIS 580 A Final Paper: Case Study Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 2 Hostess Brands, Inc. and Labor Relations Missteps I. Introduction The media extensively covered the slow death of Hostess Brands, Inc. (“Hostess”), the company that made, inter alia, Sno Balls, Twinkies, Ho-­‐Hos and Wonder Bread. This paper studies the dearth of skilled and thoughtful leadership in labor affairs throughout the company’s decline. Hostess, the private capital and hedge fund companies involved in the company, and the media widely blamed inflexible labor unions and union wages, work rules and benefits for the company’s eventual liquidation.1 For purposes of this paper, one may (but need not) assume that arcane union work rules, and union wages, health care and pension costs were at least a significant factor in the company’s demise. If the Bakery union’s strike was to blame for the final liquidation, however, it could well have been avoided through proper attention to and management of labor relations. II. Description Hostess is an 82 year old commercial bakery that sells its products to retail outlets like grocery stores and convenience stores. Even after its first bankruptcy, Hostess was one of the largest bakeries in the U.S. (Kaplan, Aug. 13, 2012). Its largest competitor was Bimbo Bakeries, and after that Flower Foods and Pepperidge Farm (Jargon & Spector, Jan 11, 2012; Kaplan, Aug. 13, 2012). 1 I view those claims with a healthy dose of skepticism, and many argued that it was inept management that killed the company, but that is an argument for a different paper. Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 3 Historically, Hostess grew by acquiring up smaller competitors, and the company went on a buying spree in the 1990s that doubled the company’s production facilities and number of employees (Jargon & Spector, Jan. 11, 2012; Macaray, Nov. 21, 2012). This created a dizzying patchwork of union contracts and a labyrinth of delivery systems (Jargon & Spector, Jan. 11, 2011). The media widely reported that the union that represented approximately 6700 delivery drivers, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (“Teamsters”), refused to eliminate redundant routes (Jargon & Spector, Jan. 11, 2011). The only Hostess union that had more members than the Teamsters was the Bakery, Confectionary, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union (“Bakery Workers”). The once iconic brand is now out of business. While other commercial bakeries innovated to increase sales, Hostess left its products as they were (Savitz, Dec. 27 2012). Between 2000 and 2010, Hostess cycled through six CEOs (Brown, Jan. 12, 2013). Hostess2 entered bankruptcy for the first time in 2004, and emerged in 2009 with approximately $110 million in concessions from its unionized employees, having closed 21 facilities and reduced its workforce from 35,000 employees to 18,000 (Kaplan, Aug. 13, 2012; Macaray 2012; “When Impasse Looms,” Feb. 2013). In return for the concessions, Hostess promised to improve its aging delivery trucks and plant equipment. Hostess never made good on that promise (Kaplan, Aug. 13, 2012). In July 2011, Hostess tripled the CEO’s salary from $750,000 to about $2.5 million per year (“When Impasse Looms,” Feb. 2013). In August 2011, Hostess 2 At the time, it was called International Brands. Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 4 stopped contributing to employee pension funds, but continued withholding the amounts from employee paychecks. Instead of directing the deducted wages (up to $4.28 per hour) to the pension funds, it used them for operating costs (Jargon, et al., Dec. 10, 2012). Also during the summer of 2011, Hostess gave four top executives raises of up to 80% (Kaplan, Aug. 13, 2012). By the end of 2011, hedge funds that had bought Hostess’s debt were driving negotiations in bankruptcy, including negotiations with the Teamsters and the Bakery workers for concessions (Kaplan, Aug. 13, 2012). In January 2012, Hostess went back into Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings, claiming that labor costs, restrictive work rules, and pension fund obligations were causing the company to be insolvent (Gross, Nov. 26, 2012; Olson, 2012; Palank, 2012). Even in bankruptcy at this time, all of the unions except the Bakery Workers settled with the company, giving concessions in wages, benefits and work rules (Gross, Nov. 26, 2012). Throughout the second bankruptcy proceedings (facetiously called “Chapter 22” by some media), the CEO communicated with employees through the public media, and conveyed threats that the company would shut down if the workers went on strike both through the media and through managers. (Keifer, 2013). III. Challenges and Evaluation of the Problem The seeds of Hostess’s labor relations problems were sown during the company’s buying spree in the 1990s. It only deteriorated with the events that followed: lagging sales and high costs leading to the first bankruptcy, failure to Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 5 restructure the company in such a way that it could become successful again, and then the brief period of failed innovations that led to the second bankruptcy. The corporation began to change and its labor relations became much more complicated as it swelled with the employees and production facilities of the companies it acquired (Jargon & Spector, Jan. 11, 2012). During the 1990s, the myriad acquisitions resulted in legacy pension and medical benefit obligations, inconsistent and restrictive work rules, and redundant delivery routes (Macaray, 2012; Olsen, 2012). This suggests numerous missed opportunities. Companies pursuing a strategy of profit growth by acquisition usually attempt to acquire businesses and then shut down redundant facilities and functions and layoff redundant employees as soon as possible. There are significant costs to integrating acquired companies, including “right-­‐sizing” after acquisitions, and those costs rise significantly with time. Hostess did not assimilate the acquired bakery companies expediently and skillfully. If Hostess management had thoughtfully and expeditiously absorbed the companies they acquired, they would have standardized work rules, wages and benefits as they went. As a former labor lawyer who represented Teamsters, I know that Teamsters often negotiate “master agreements” that govern all of an employer’s locations, even across state lines (See, e.g., PRNewswire 2006, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, n.d.). Some of these agreements, such as the National Master Freight Agreement, govern entire industries and apply to many employer signatories in that industry (International Brotherhood of Teamsters, 2008). Hostess missed their opportunity during the acquisitions phase of their growth to Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 6 negotiate such an agreement. In addition, employers, even if they are unionized, can lay off employees. They must negotiate over the effects of the layoffs, but ultimately companies can decide how many people to lay off and when to lay them off. If Hostess’s acquisitions caused redundancies in delivery routes, they missed opportunities to bargain over and implement layoffs during and after the acquisitions to eliminate those redundancies. After the buying spree and the resulting complicated, inconsistent and inefficient labor landscape had developed, the first bankruptcy proceeding created a lot of “bad blood” between labor and management. Management had not addressed the ongoing problem of its own credibility and trustworthiness. The significant concessions extracted during negotiations in the proceeding were difficult for the unions to swallow. Pension costs were still high, and the negotiations caused the unions to distrust management (Jenkins, Nov. 28, 2012). In addition, the company had not innovated its product line, nor modernized its delivery and manufacturing equipment, further undercutting management’s credibility. Furthermore, right or wrong, the union employees felt like they had been scapegoated for what, in their view, were bad management practices. In addition to souring labor relations, the first bankruptcy proceeding represents another missed opportunity. Management clearly did not bargain for what it actually needed to put the company back on solid footing. This is evident because the company got significant concessions in terms of wage cuts and layoffs during the first bankruptcy proceedings, but when they returned to bankruptcy for the second time, they still blamed legacy pension and medical benefit obligations Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 7 and restrictive work rules (Jargon & Spector, Jan. 11, 2012, Olsen, 2012). Further, the company was back in bankruptcy within a couple of years. In the interim between the two bankruptcy proceedings, Hostess missed opportunities to rebuild trust with its organized workforce. Instead of working to rebuild trust and rapport, Hostess: maintained a revolving door for CEOs; gave significant raises to management; reneged on promises to modernize bakery equipment and delivery trucks to improve working conditions, productivity and efficiency; stopped making contributions to pension funds; and took money bakery workers allocated to their pension funds and used it for operating costs. Ultimately, before and during the second bankruptcy proceeding, Hostess further poisoned the relationship by loudly and publicly continuing to blame the unions for its continued losses. In the second bankruptcy proceeding, Hostess had four tiers of secured debt totaling approximately $850 million, held by a capital financing company and two hedge funds, a private equity firm, and another approximately $137 million in secured debt owned by the hedge funds. Further, there was a $105 million secured loan from another capital firm and another $86 million in secured notes due in 2019. This meant that in the event of liquidation, the unions’ pension and even wage claims would not be paid. That gave Hostess significant bargaining power, because if the company did not survive, the employees had no hope of recovering unpaid wages or benefit contributions (Sheahan, Jan. 26, 2012). In summary, the company was in worse financial straights than ever, with little of value to offer in return for Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 8 needed concessions and less political capital to spend in trying to get the unions to come along. From 2000 on, the company’s actions described above created and continually deepened worker suspicion about management. This inevitably made negotiations more contentious, difficult and slow. Further, these actions and failures to act made the employees feel that the company was doomed, that they could not rely on the company to honor its commitments, and that further concessions would be futile. Meanwhile, management’s failure to respond to external forces and internal forces that were not directly related to labor also undercut worker, creditor, and public confidence in Hostess management. The Great Recession caused consumers to cut costs and reduce consumption of many consumer goods, including packaged snacks (Kaplan, July 26, 2012). Prices rose for flour, sugar and other ingredients (Spector & Jargon, Jan. 10, 2012). Gasoline prices also rose, and that affected delivery costs (Spector, Sept. 2, 2011). In light of these increased costs, the company had considerable difficulties pricing their products competitively. Further, Americans were becoming more health conscious (Forbes, Nov. 28, 2012; Gross, Nov. 26, 2012; Spector, Sept. 2, 2011). Hostess did not make product innovation a priority, and what little innovation Hostess did generate was far too little and far too late (Gross, Nov. 26, 2012; Savitz, Dec. 27, 2012; Spector, Sept. 2, 2011). Finally, there had been no investment in marketing and promotion since 2002 (Jenkins, Nov. 21, 2012). Hostess utterly failed to respond to these external forces, and that made them look hopelessly incompetent. Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 9 While they are not directly related to negotiations with organized labor, unions and their members were acutely aware of these forces. Management’s failure to be proactive in the face of these challenges created a lack of confidence in the employees. The employees began to reason that either management lacked competence to bring the company back from the brink, or it lacked the desire to do so. Either way, they company would fail, and giving concessions could not change that. Perhaps more important, though, workers and their union representatives felt that these forces beyond their control were significant factors in the company’s troubles – as significant, if not more significant, than the wages, benefits and work rules in the union contracts. So, management’s failure to proactively address these challenges raised a sense of indignation in the employees. It was this sense of indignation, combined with feelings of futility that led the bakery workers to go out on strike. IV. Recommendations As a manager or a consultant hired to assist the company, I would have taken a completely different approach to labor relations throughout Hostess’s recent past. First, during and after acquisition binges, it was imperative that Hostess make labor agreements more consistent across the company. During acquisitions, I would be working with the existing union locals and the international union to develop a master labor agreement. The most important points for negotiation would be uniform work rules throughout the company and benefits fund contributions. This makes it possible to create a uniform and rational delivery system and to a single-­‐employer pension fund. Upon expiration of each contract, I would ask the Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 10 local union to sign on to the master agreement that had already been negotiated. Any issues outside the master agreement and specific to the work site could be negotiated in a traditional unit-­‐wide collective bargaining agreement. Second, it is critical to have a stable leadership team throughout a crisis. I would make every attempt to limit turnover in upper management and to have a single person as primary contact for the union. Even if it was impossible to maintain one CEO throughout, I would make sure the unions could deal with the same top-­‐ tier manager throughout. This creates an opportunity to build rapport and create follow-­‐through on promises. Trust and credibility built through a long-­‐term relationship can be drawn upon later when concessions become necessary. Third, it is critical for the management team to treat workers with integrity and to show empathy throughout the crisis. For this reason, the primary channel for company communication should be frontline managers who know and care about the workers. These managers would be trained to help deliver the company’s message in an honest, forthright and sensitive manner. Written communications would be sent directly to employees’ homes. Perhaps most important, all news would first be communicated to employees before it was communicated to the media. In addition, all wage deductions must be accounted for and used properly. If wage deductions were misappropriated under my management, they would immediately be restored either directly to the employee as wages or to the employee’s pension fund account as intended, cash flow and bottom line be damned. Fourth, in initial bankruptcy proceedings, my goal would be to get all the concessions I needed to make the company profitable, including layoffs and Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 11 elimination of redundant delivery routes and wage and benefits concessions that bring workers within the range of their counterparts at other companies. My priority in this proceeding would be to create a final deal that both sides could stick with indefinitely. The reason for this is that any attempt to force a second round of concessions would be viewed by the unions as a betrayal and reneging on a promise. Fifth, after the first bankruptcy proceedings, I would be bound and determined to make good on any promises made in return for the concessions won, especially modernization of equipment to make the workforce more profitable. I would rattle every cage needed to make good on those promises, including the cages of managers superior to me. Sixth, after the bankruptcy proceedings and when the company was swirling down the drain, I would not, under any circumstances, give significant pay increases to upper-­‐level management. It is not at all that this is a problem for the bottom line. I recognize that raising salaries for 8 people does not make a significant dent in a budget that runs in the hundreds of millions. However, it is of tremendous symbolic importance to the rank and file production and delivery workers. When we triple the CEO’s salary, the workers will not believe that the company truly needs to cut labor costs. It is callous and reminds employees of how out-­‐of-­‐touch management is with worker concerns. They cannot believe that a person who makes even $750 thousand dollars per year cannot understand what it means to reduce pay for someone who makes $16 per hour. Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. VI. 12 Conclusion By thinking strategically and long-­‐term, and by using empathy and integrity throughout the crisis, Hostess could have gotten a different result from its labor relations. If the unions’ contracts were, in fact, responsible for the demise of Hostess Brands, Inc., the company’s liquidation could have been avoided with smart, thoughtful management of labor relations. Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 13 References Bread & Rolls Industry Profile: United States. (2012, November). Bread & rolls industry profile: United States, 1-­‐36. Brown, A. (2013, January 12). Sticky math behind Hostess: How much are Twinkies and Wonder Bread worth? Forbes.Com, 7. Brown, A. (2013, January 22). Hostess: Two new private equity shops want in. can they do a better job?. Forbes.Com, 22. Forbes, M. (2012, November 28). Why are food fascists still weeping over Twinkies? Forbes.Com, 47. Gross, D. (2012, November 26). R.I.P., Twinkies. Newsweek, 160(22/23), 6. International Brotherhood of Teamsters. (April 1, 2008). National master freight agreement for the period April 1, 2008 through March 13, 2013. Retrieved on March 15, 2013 from http://www.teamster.org/sites/teamster.org/files/2008-­‐2013_NMFA.pdf. International Brotherhood of Teamsters. (N.D.) Master freight agreement. Retrieved on March 15, 2013 from http://www.teamster.org/history/teamster-­‐ history/freight-­‐agreement. Jargon, J., & Spector, M. (2012, January 11). Hostess tries to lengthen shelf life. Wall Street Journal -­‐ Eastern Edition. pp. B1-­‐B5. Jargon, J., Feintzeig, R., & Spector, M. (2012, December 10). Hostess maneuver deprived pension. Wall Street Journal -­‐ Eastern Edition. pp. C1-­‐C2. Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 14 Jenkins,Holman W.,,Jr. (2012, November 21). Twinkies: A defense. Wall Street Journal, pp. A.15. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1178229343?accountid=14784 Jenkins, H. W., & Jr. (2012, November 28). The media choke on a twinkie. Wall Street Journal, pp. A.13. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1220342592?accountid=14784 Kaplan, D. A. (2012, August 13). Hostess is bankrupt…again. Fortune, 166(3), 60-­‐67. Macaray, D. (2012, November 21). Labor union unfairly blamed for the Hostess meltdown. Huffington Post Business Blog. Retrieved on March 15, 2013 from: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-­‐macaray/labor-­‐union-­‐hostess-­‐ twinkies_b_2161368.html Olsen, K. (2012). Pension obligations help push Hostess Brands into bankruptcy. Pensions & Investments, 40(2), 15. Palank, J., Spector, M., & Jargon, J. (2012, January 12). Hostess files for chapter 11. Wall Street Journal -­‐ Eastern Edition. p. B3. Savitz, E. (2012, December 27). 7 Lessons from the rise and fall of the Twinkie. Forbes.Com, 15. Sheahan, M. (2012, January 16). This time, Hostess hopes to get it right. High Yield Report, 23(3), 12. Spector, M. (2011, September 2). Hostess again hires advisers. Wall Street Journal -­‐ Eastern Edition. p. B6. When impasse looms, bring them back from the brink. (2013, February). Negotiation, 16(2), 6-­‐7. Dropping the (Sno) Ball: Labor Relations and Hostess Brands, Inc. 15