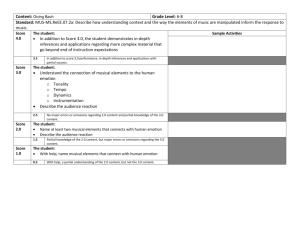

Education Research Studies in Music

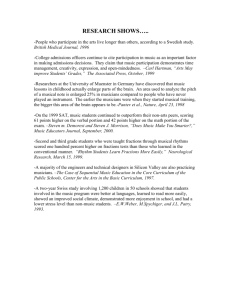

advertisement