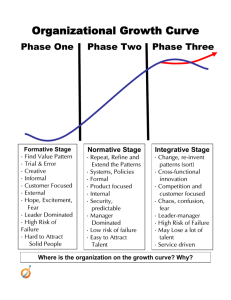

Best practice and key themes in global human resource

advertisement