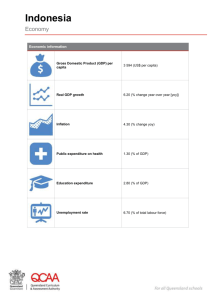

Assessing Indonesia's Tax Optimization

advertisement