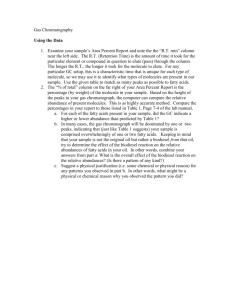

genetic engineering of chlorella zofingiensis for

advertisement