How_Parents_Are_Being_Misled

advertisement

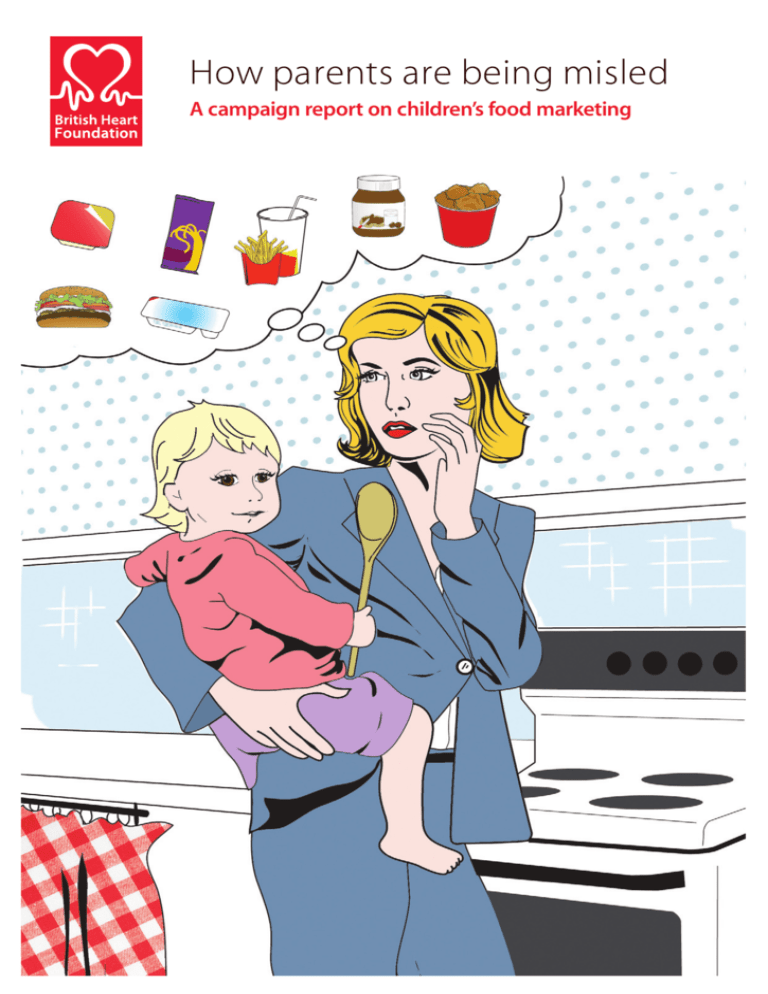

How parents are being misled A campaign report on children’s food marketing The British Heart Foundation is the nation’s heart charity, dedicated to saving lives every day through pioneering research, campaigning for change, caring for patients and families, and providing vital information to help people keep their own hearts healthy. Foreword Healthy eating and children’s diets have never been higher up on people’s list of concerns and everyone agrees that parents are key to making healthy food choices for families. But how can they do this in the current environment? The riot of messages in the media and on food packaging leaves them bewildered about what is really best for their kids. Even when parents are able to take the time to sift through the information they are being given about nutrition, this may not help if the food labels only give them part of the story. For the first time, this report examines the ways that food companies are playing on parents’ concerns to actively market children’s food that is high in sugar, fat and salt. They are being overloaded with messages about what is best for their children’s diet and hindered from making informed choices. That’s why we are demanding that the UK Government creates an environment that empowers parents by rigorously limiting the marketing of unhealthy foods and making sure that labels are clear and consistent. And we’re asking parents to join us in campaigning for an end to the techniques that allow companies to mislead them. We know that obese children are more likely to become obese adults and this could have serious implications for future levels of heart disease. We must all play our part to stop this happening. I hope you agree that the findings in this report underline the need for urgent action. Peter Hollins Chief Executive British Heart Foundation Acknowledgments The British Heart Foundation and The Food Commission wish to thank all the parents, childminders, and subject specialists who took part through interviews and workshops. Particular thanks are due to the authors Anna Glayzer and Jessica Mitchell. We also wish to thank Jane Landon of the National Heart Forum for her valued support and guidance. 2 3 Introduction The aim of this report Our children are at risk. Since the introduction of legislation which partly restricts the promotion of high fat, sugar and salt (HFSS) foods directly to children, food companies are increasingly targeting parents in their efforts to retain and increase their share of the hugely lucrative food market. By using subtle marketing techniques and health claims that play on parents’ fears and aspirations, they are reducing parents’ ability to make the choices they need to safeguard the health and well-being of their children. Parents obviously play the most important role in providing and encouraging a healthy diet for their children, and with the continuing rise in childhood obesity, this role is becoming increasing vital for the future health of all our children. This report provides evidence to support these claims, and proposes the urgent action that we need to take to control this threat to our children’s future health. Obesity is one of the most significant long-term health problems facing us today Almost two out of three adults and one in three children are overweight or obese.(1) And, if this trend continues: By 2050, overweight or obesity will affect nine out of ten adults and two out of three children.(2) This is all the more disturbing because obese children are more likely to remain obese in adult life(3) and in doing so are more susceptible to related illnesses such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, Type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease and cancer. Clearly, poor diet plays a major role in the growing ‘epidemic’ of obesity.(4) There is evidence that, on average, our young people are consuming sugar, saturated fat, and salt above the maximum recommended levels, while 80% of them are not getting their ‘5-a-day.’ (5,6,7) There has also been a significant decrease in physical activity with a ten per cent drop in the number of children walking to school in the last two decades and increases in the amount of time children spend in front of a TV or computer screen.(8) Trade publications have suggested a growth in the marketing of HFSS children’s foods to parents since the Ofcom restrictions came into place.(14) One article, Food advertising shifts focus from kids to parents ,(15) suggested that: ‘After years of ignoring parents in favour of their children, brands, particularly in the food sector, have found that legislation and growing opposition to advertising to the latter means they are being forced to open a dialogue with mothers and fathers.’ Until now, this issue has had little or no public examination. This report assesses the marketing of unhealthy HFSS children’s foods across a range of media. Although it doesn’t cover the entire children’s food market, the evidence shows that, far from doing all they can to help parents raise healthy children, companies are using television and print adverts, product packaging and other non-broadcast media to attract parents to HFSS products aimed at the children’s market. It also shows that a range of sophisticated marketing techniques are used to manipulate parents into thinking they are buying healthy food for their children and that current regulations on advertising and food packaging do not adequately support parents in making healthy food choices. The examples of marketing HFSS children’s foods to parents in this report were collected from mainstream television channels, magazines, and branded product packaging. Examples were also collected from company websites and from the websites of commercial and non-commercial organisations working with schools. All examples were collected between 14 August and 27 September 2008. For more details on the methodology and findings of this report, please refer to the Background Report on our website bhf.org.uk/junkfood Although many food companies have long targeted children as an important market for their HFSS products, extensive campaigning by the BHF, in partnership with other groups, is making significant progress in the fight to help our children live longer and healthier lives. These campaigns, and the Hastings Report,(9) which showed that promoting HFSS foods to children has a negative influence on diets, helped convince the Office of Communications (Ofcom) of the need for change. Legislation is now in place to restrict the advertising of these foods in or around programmes of particular appeal to both pre-school children and children aged four to 15 years. However, there is still much to be done. Because the majority of children’s television viewing (68.9%) is outside dedicated children’s programming, tougher legislation is clearly needed(10) to prevent children from seeing HFSS advertising during family shows such as X-Factor, Emmerdale or Kids Do The Funniest Things .(11) HFSS food and drink products, and the brands associated with them, are still marketed to children on television and through non-broadcast media, particularly company websites, viral marketing, mobile phone marketing and the use of licensed characters, and other promotions, on product packaging.(12) The UK Government’s role in reducing the impact of marketing on children’s health is crucial, and it has gone some way in (13) working with the food industry to achieve this. The ten year strategy Healthy Weight Healthy Lives identified parents, and food companies, as central to ensuring children have healthy diets. This sets out a vision of a society where parents have the knowledge and confidence to ensure children eat sensibly, and food, drink and other related industries support this through clear and consistent information, doing all they can to help parents raise healthy children. 4 5 The Media debate The regulatory context The reasons parents buy, and children want, certain products are significantly different. A report(16) produced for businesses who wish to market children’s foods to parents, said factors which drove parents’ purchasing decisions included: Concern Guilt Nutritional content Desire for perfect child Insecurity Aspiration and Control. The following is a short summary of the regulatory bodies who cover broadcast and non-broadcast media. For a fuller explanation, please see the Background Report at bhf.org.uk/junkfood While key factors driving kids’ purchasing decisions were listed as: The CAP code for non-broadcast media includes rules for print advertising in newspapers, magazines and online. Internet advertising in paid for space, such as pop up ads, is covered by the CAP code, but most of the content of company websites would be classified as editorial, and is therefore not subject to the code. There is some regulation for internet advertising and commercial activity in schools. There are no specific rules on marketing HFSS children’s foods to parents.(28) Fun Taste Brand Peer-pressure Status and Packaging. Regulatory bodies and their codes The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA)(26) is a self-regulating body set up by the advertising industry to regulate the content of UK adverts, sales promotions and direct marketing, and ensure the industry adheres to the advertising codes. It is also responsible for investigating complaints against specific advertisements. The Committee of Advertising Practice (CAP) oversees the UK’s advertising codes, which are called CAP codes. There are separate CAP codes for broadcast media - television and radio - and for non-broadcast media.(27) The CAP codes aim to ensure marketing is ‘legal, decent, honest and true,’ and have been revised to try to prevent the encouragement of poor nutritional habits and unhealthy lifestyles in children. Ofcom regulates the broadcasting, telecommunications and wireless communications sector in the UK. Current Ofcom restrictions are, in essence, that advertisements for HFSS products must not be shown in or around programmes: It is clear that some companies are targeting both parents and children. One conference, entitled, ‘How do you create effective yet ethical, campaigns that excite both children and their parents?’ was attended by more than 100 representatives of top selling brands, and focused on how to find ‘creative ways of working within the legislation.’ (17) Company executives were quoted in trade publications on ways children’s foods are marketed to parents.(18) Neil Brown, Princes Foods’ Marketing Director said: “Targeting children directly is not the way forward. Companies need to be bringing out products that appeal to parents on health and convenience grounds”. (19) Advertising Executive Craig Mawdsley also said: “The message that you give parents is the flipside of the one that you have been telling their children”. (20) Specifically made for children or at all on dedicated children’s channels; or Of particular appeal to children under 16.* Consumer groups have recently demonstrated that family programmes watched by high numbers of children and adults are not covered by the restrictions and continued to show HFSS ads.(29) The Ofcom restrictions are currently under review. Companies are also using the more subtle technique of ‘emotional insight’, eg, guilt and nostalgia, to attract parents. For example, Marketing magazine said that Fab lollies advertising: “…reminded parents of their own childhood, playing on the nostalgia aspect of the brand.“ (21) There can be a blurring of the lines between target audiences for advertising campaigns. Some companies were either reported to be, or said they were, targeting parents but not children: “The company [McDonald’s] says it no longer advertises to children, despite the fact that doing so online remains legal.” (22) And also that: “McDonald’s is overhauling its Happy Meals toys to push an educational message among parents”. (23) “There are glaring inconsistencies between regulations concerning broadcast marketing and regulations concerning non-broadcast marketing which make a nonsense of any attempt to reduce children's desire for HFSS products.” Tim Lobstein, Director, Childhood Obesity Research Programme, International Association for the Study of Obesity. Other companies did not claim to be targeting parents to the exclusion of children: “In a shift of strategy, Burger King has launched its first campaign to explicitly target mothers.” And that this new print campaign would promote, ‘fun food for kids that parents can trust.’ (24) And Jane James of Honey Monster Foods said: “We couldn’t target children directly... but our brand has such a long heritage that we decided instead to advertise to adults to remind them about Sugar Puffs.” (25) * For more information, please refer to the Background report at bhf.org.uk/junkfood 6 7 Other regulations Most of the rules regarding the packaging of products are derived from The Food Labelling Regulations 1996. The relevant regulations here cover: Claims which a product may or may not make What nutrition information must be provided, and Potentially misleading product descriptions, such as ‘dietary’. Guidance for schools is solely self-regulatory. Working with schools - best practice principles, developed jointly by the Department for Children, Schools and Families and the Incorporated Society of British Advertisers provides a checklist for schools and a checklist for external partners to help judge whether the proposed venture is in line with best practice. What we found This chapter outlines our assessment of the marketing of HFSS foods to parents across a range of broadcast and non-broadcast media, such as company websites and product packaging during the period 14 August – 27 September 2008. We focused particularly on breakfast and lunchtime foods, where marketing of foods aimed at children can be clearly delineated. “The debate leading up to the introduction of the Ofcom television advertising restrictions helped companies to think about the nutritional values of their products. Some companies took action to change nutritional values, and some simply re-branded by focusing attention on particular elements of nutrition.” Kath Dalmeny, Policy Director, Sustain. 8 9 How we did it The Food Standards Agency has developed a nutrient profiling model (NPM) to categorise foods on the basis of their nutrient content. This measures the energy, saturated fat, sugar and salt content of products and awards points to give a simple guide to whether or not a product is an HFSS food. Points are added according to levels of saturated fat, sugar and salt, then points are deducted for fruit and vegetables, nuts, dietary fibre and protein. If the overall score is 4 or greater, the product has HFSS status and cannot therefore be advertised on children’s television. All the products we examined have a score of 4 or above. We have used a graphic to illustrate their score as shown below. NPM rating: 0 4 30 0 4 20 30 NPM rating: The left graphic shows the NPM rating for a healthy product. Any score above 4 means that the product is high in fat, sugar and salt (see right graphic). For further information on the NPM, please see the Background Report at bhf.org.uk/junkfood To evaluate the marketing methods used by food manufacturers to promote high fat, salt and sugar products to parents we developed a Checklist of seven commonly used marketing techniques. Broadcast media: The following examples illustrate how the techniques included in our Checklist are used in television advertising to attract parents to HFSS foods or brands, for consumption by children and the rest of the family. They are not intended to be comprehensive, but to provide an indication of how parents are being directly targeted. The techniques we looked at were: Nutrition claims – eg, ‘good source of calcium’ Health claims – eg, ‘good for growing kids’ Quality claims – eg, ‘wholesome’ Images – eg, of happy family life Promotion – eg, special offers likely to appeal to families Emotional insight – eg, tapping into parents’ guilt over not having time to cook Endorsement – eg, by a nutritionist or sports personality. The products appearing in this report were marketed using at least two of the techniques highlighted in our Checklist. A key characteristic of the product examples used is that the marketers have used Checklist techniques to accentuate notional benefits and chosen to hide or obscure the complete nutritional content of the foodstuff. This misleads parents. A fuller description of these techniques is given in our Checklist (Appendix) on page 34. We also spoke to parents and carers who confirmed that the marketing of children’s HFSS food is an issue for them, and we have included some of the things they told us in this report. “Why don’t they advertise having fruit? You don’t see any adverts for healthy eating. They need to be doing TV adverts that are in your face. People would definitely take notice.” A parent. Throughout the examples below, we have colour-coded the saturated fat, sugar and salt contained in the products according to the Food Standards Authority’s Multiple Traffic Light system, which defines: 10 A green light as ‘low – a healthier choice’ An amber light as ‘medium – ok most of the time’, and A red light as ‘high – just occasionally.’ Low Medium High a healthier choice ok most of the time just occasionally Sugars 5g or less 5.1g - 15g more than 15g Fat 3g or less 3.1g - 20g more than 20g Saturates 1.5g or less 1.6g - 5g more than 5g Salt 0.30g or less 0.31 - 1.5g more than 1.5g All measures per 100g 11 Example 2: Example 1: KFC Deluxe Boneless Box Mini fillet 0 4 14 30 Kellogg’s Rice Krispies Kellogg’s Rice Krispies 0 NPM ratings: The advert 15 Popcorn chicken A girl is jumping up and down on her bed grinning. Her mother calls up: “Have you cleaned your bedroom yet?” The child shouts back: “Yes!” Another girl is lying on the grass stroking a guinea pig. The same woman’s voice calls: “Have you cleaned the hutch yet?” The girl responds with a yes. A boy is running around next to a half lathered car with a dog and a hose. The same woman calls: “Have you cleaned the car yet?” The boy responds with a yes. A voiceover tells viewers: “At least they’ll clean their plates, with the KFC Deluxe Bonus Box. Eight pure breast Mini fillets, Popcorn chicken, fries, sides and a bottle of Pepsi.” As the voiceover starts the music becomes more upbeat and shots of the respective products appear as they are listed. Then, all three of the children, along with a mother and a father are shown sitting around a kitchen table, a pile of KFC wrappers in the middle. The mother says: “Right, I’ll clear up.” “It’s alright mum, ” replies the boy, “we’ll do it.” As he speaks, he gets up from the table and picks up a plate. “Polish off the KFC Deluxe Boneless Box, only £12.99” says the voiceover. Viewers are shown a group shot of all the items in the Boneless Box, and text at the bottom of the screen confirms, ‘KFC Deluxe Boneless Box Only £12.99.’ Finally the KFC logo and catchphrase, ‘Finger Lickin’ Good’ appear. 4 12 30 NPM rating: The advert Three children are seated at a table eating breakfast. Their mother is standing up pouring out some of the cereal for one of the children. One of them asks her how many grains of rice there are in a bowl of Rice Krispies. Reading the pack, while nodding her head and raising her eyebrows to form an expression that suggests she is impressed, she replies: “The pack says 1500, which is quite a lot of rice. ”The children spontaneously decide to count how many ‘snap crackle and pops’ they can hear. As they do this, the mother leans against a counter in the background eating cereal from a bowl. She then re-joins the children to ask them how many there were, which results in general mirth as it emerges one of the children was eating during the count. A voiceover says:“Kellogg’s Rice Krispies, with lots and lots and lots of little grains of goodness.” KFC Deluxe Boneless Box TV commercial stills Kellogg’s Rice Krispies TV commercial stills Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Quality claim: ‘Deluxe.’ Images: Healthy happy looking children bouncing on the bed energetically, playing caringly with a guinea pig, boy out doors, playing energetically and caringly with a dog, family all healthy and happy looking, eating together, around the table. Promotion: The price is described as “Only £12.99,” which gives the impression that this is a promotional deal. Emotional insight: In all three of the situations prior to the meal, the children are not doing the chores they have been asked to do. In contrast, having eaten from the “Deluxe Boneless Box,” the children clear the plates voluntarily. The advert thus uses emotional insight by sympathising with the difficulty mothers have in trying to get their offspring to help them with chores. Quality claim: ‘Little grains of goodness.’ Images: Healthy, happy looking children smiling at and laughing with their mother in a clean and well ordered kitchen. Emotional insight: While the children behave in an ideal manner, enthusiastically and entirely voluntarily engaging in an educational counting activity, the mother has to eat her breakfast standing up in the background, using the emotional insight that many parents have busy, rushed breakfast times. “My son is reciting the fact that food is good for him because the ad on telly tells him it is.” A parent. Saturated fat, sugar and salt content:* Saturated fat, sugar and salt content: There is more than half of a child ’s daily recommend ed maximum salt intake in a serving of Popcorn chic ken. 12 Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g Popcorn chicken 257 kcal 3.16g 0.35g 2g Mini fillet 171 kcal 1.43g 0.36g 1.96g Kellogg’s Rice Krispies Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g 381 kcal 0.2g 10g 1.6g *The nutritional information per 100g was calculated by BHF from KFC data on their website which states nutritional information per portion. 13 Example 1: Burger King Aberdeen Angus Mini-Burger with cheese BK Angus Mini Burger (cheese) 0 4 12 30 NPM rating: Print marketing examples: The following example illustrates how all seven techniques from our Checklist are employed in print adverts to market HFSS children’s foods to parents. Burger King print advert, Red magazine, published Sept’ 2008 Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Nutrition claims: ‘100% flame grilled certified Aberdeen Angus,’ ‘quality ingredients.’ Images: A healthy looking smiling mother in a strong stance. She is covered with cooking utensils, bringing to mind home food preparation. Emotional insight: The woman’s stance and ‘armour’ make her look gladiatorial, while the text, ‘The lunch battle is over’ and ‘finally food you can agree on’ refers to, and empathises with, the common difference of opinion between mother and child when it comes to choosing food. Her smile suggests that she has managed to avoid conflict and feels content with what her child is having for lunch. Promotion: A ‘free kids meal upon purchase of an adult meal.’ Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: There is more than a fifth of a child ’s daily recommend ed maximum saturated fat intake in a BK Angus M ini Burger with cheese . 14 BK Angus Mini Burger with cheese Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g 287 kcal 6g 5g 0.93g 15 Example 3: Example 2: Nestlé cereal and Nesquik advertising promotion in Sainsbury’s Magazine Natural Confectionery Company Jelly Snakes Straws - strawberry Coco Shreddies 0 4 8 15 Nat’ Conf’ Jelly Snakes 30 0 NPM ratings: 9 Cheerios 4 13 30 NPM rating: 21 Straws - choc’ Nestlé Cereal and Nesquik advert, Sainsbury’s Magazine Sept’ 08 Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Nutrition claims: ‘Added vitamin d,’ ‘no artificial colours,’ ‘wholegrain,’ ‘vitamins minerals and fibre.’ Health claims: ‘Help kids maintain strong, healthy bones,’ ‘find your get up and go in the morning,’ ‘energising’. Quality claim: ‘Full of goodness.’ Images: Smiling, healthy looking children seated at a table in a clean well ordered kitchen next to a fruit bowl and a smiling, healthy looking girl seated in pleasant looking outdoor setting. Promotion: ‘Go Free’, where consumers can collect vouchers for free sports lessons - a ‘3 for the price of 2’ offer. Emotional insight: The common conflict between parents and children over food choices is invoked and an apparent solution suggested. In this case the insight is the understanding that parents want their children to consume certain nutrients, but that children can oppose them. The advert notes that, ‘some children find the taste of plain milk hard going,’ before going on to ask, ‘So why not bring some fun to the breakfast table with a chocolate or strawberry flavoured Nesquik Magic Straw as a great way to help them polish off their cereal milk!’ Endorsement: The retired athlete Daley Thompson is recognisable on cereal boxes on the bottom of the first page. Natural Confectionery print ad, Sainsbury’s Magazine, Sept’ 2008 Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Nutrition claim: ‘No artificial flavourings or colourings,’ ’natural.’ Emotional insight: The advert refers to the clash between parent and child when it comes to food choice. By appealing to ‘mums who like to say no,’ the advert makes reference to the common feeling among parents that it is not always easy to say no in the face of pester power, and in fact in this instance, parents can say yes to requests for sweets, but no to artificial flavours and colourings, thereby pleasing the child and feeling reassured that they are getting something that does not contain additives. Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: If, as is sugges ted in the te xt and by the pi ctur had a bowl of e, a child Cheerios with milk alongsid ea milk flavoured glass of with Nesquik Strawberry, at the recomm ende servings, they would consum d 37.4g sugar. e 16 Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g Coco Shreddies 358 kcal 0.7g 29.4g 0.7g Cheerios 369 kcal 1.1g 21.6g 1.2g Nesquik Magic Straws: Strawberry 372 kcal 0g 58.9g 0g Nesquik Magic Straws: Chocolate 341 kcal 1g 44.7g 1.5g Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: Images 1 - 8: Nestlé Cereal and Nesquik advert, Sainsbury’s Magazine Sep 08: pages 1 & 2 Despite hav ing no artificial co lours or flavourings, sugar comprises more than half the co ntent of Natural Co Nat’ Conf’ Jelly Snakes nfectionery Company sw eets. Energy kcal per 100g 295 kcal Images 5 - 8: Natural Confectionary Saturated print ad,Fat Sainsbury’sSugar Magazine, per 100g 2008 per 100g September Trace 50.5g Salt per 100g Trace 17 Example 1: Nestlé Honey Shreddies Nestlé Honey Shreddies 0 4 8 30 NPM rating: Non-broadcast media: Product packaging examples The following examples focus around two key meal occasions, breakfast and packed lunch. The analysis demonstrates how all seven of the techniques from our Checklist are used on product packaging in order to market HFSS children’s food to parents. Examples of breakfast food Breakfast is a key meal of the day and often a time when families eat together. This is reflected in the examples outlined in this section. Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Nutrition claims: ‘Wholegrain foods contain a combination of protein, fibre, vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and carbohydrates.’ Health claims: ‘Helps you get 3 a day wholegrain’ (In very large letters on front of pack), ‘keep your heart healthy and help maintain a healthy body’ , ‘We are meant to eat at least three portions of wholegrain everyday to help our bodies function effectively’ , ‘Nestlé Cereals helping you on your way to 3-a-day.’ Above the nutrition panel and ingredient information, with arrow pointing to the information, text reads, ‘it’s good to know.’ Images: Healthy, happy, family running energetically through a corn field. Pictures of smiling mother and child on side panel; and the friendly looking ‘nana’ character. Promotions: A send away token for ‘box top books’ , ‘visit the Shreddies factory online to play games and watch films.’ Emotional insight: The old fashioned ‘nana’ character with pearl necklace, slippers and kitting is likely to induce feelings of nostalgia in parents. Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: Nestlé Honey Shreddies 18 Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g 359 kcal 0.3g 30.3g 0.7g 19 Example 2: Examples of food stuff for children’s packed lunches Nutella Children’s lunchbox food is a growth area. Research by Yoplait showed that in 2006 58% of mums had made a child’s lunchbox in the last two weeks; in 2007 this rose to 69%.(30) This is therefore clearly an important part of the children’s food market. Nutella 0 4 26 30 NPM rating: However, there is some evidence to indicate that the food included in packed lunches is less healthy than school lunches, which are governed by nutritional standards. Researchers at the University of Plymouth compared packed lunches with school lunches and found that packed lunches: Contained a higher amount of saturated fat Were higher in salt Obtained twice as much energy from sugar than the school lunches.(31) This section examines children’s food products that are marketed to parents for use in packed lunches. Example 1: Cheestrings Original Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Cheestrings 0 4 22 30 NPM rating: Nutrition claims: ‘Free from artificial colours and preservatives,’ ‘over 25 hazelnuts in every jar.’ Quality claims: ’The delicious taste of nutella that kids love,’ ‘Breakfast with Nutella: Make Nutella part of a balanced breakfast.’ Images: These claims are in speech bubbles with arrows pointing at a picture of healthy foods including wholemeal toast (in a neat toast rack as might be used on a family breakfast table) and a glass of orange juice. A huge, bright yellow sun is rising in the background. Summary of techniques used to market to parents: “I am thinking about the price, what information is given about sugar and salt, what my son likes. I also have to shop fast when I am with my kids, so the packaging matters too. I don’t necessarily trust all of the information the same, but I have to go on what information and time I have.” Nutrition claim: ‘Good source of calcium and protein.’ Health claim: ‘For healthy teeth and bones.’ Quality claim: ‘Real cheese goodness.’ Promotion: ‘Cheestrings Challenge: Cheestrings Supports Swimming. Get involved at www.cheestrings.co.uk’ Endorsement: The product is ‘International Dental Health Foundation Approved.’ A parent. Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: A recent te levision a d for Nutell a was ban ned on the gro un the advert ds that suggeste d the produ ct nutritious is more than it is. Nutella Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g 530 kcal 10.7g* 56g Trace One Chee stri stick conta ngs ins nearly a sixth of a child’s daily reco mmende d maximum saturated fat intake . Cheestrings Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g 325 kcal 14.8g 0g 1.9g *Saturated fat content not specified on label, information obtained from company website 20 21 ParentsbeingmisledFinal.pdf 11/3/09 14:17:45 Example 4: Example 2: Dairylea Bites Dairylea Bites 0 4 24 30 NPM rating: Müller Crunch Corner Snack Size (choco balls & toffee caramel balls) Crunch corner 0 4 5 30 NPM rating: Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Nutrition claim: ‘No artificial colours, flavours or preservatives added.’ Quality claim: ‘Real cheese goodness.’ Image: A cartoon style cow character. Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: One Dairylea Bite contains a fifth of a child’s daily re commended maximum salt intake. C Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g 328 kcal 17.5g 0.1g 3.5g Dairylea Bites Nutrition claim: ‘No artificial colours or preservatives,’ ‘no artificial sweeteners,’ ‘source of calcium’ Quality claim: ‘Ideal for lunchboxes.’ Image: Lunchbox logo on the front of the pack. The back of the pack features picture of the ‘Müller Crunch Corner Snack Size’ in a lunchbox, in which healthy foods such as grapes, a banana, an apple, and a sandwich made with wholemeal bread are visible, as well as another Müller product, which makes these products seem healthy by association. M Y CM Emotional insight: ‘Post-it’ notes with suggestions of healthy meal options written underneath the days of the week are pictured on the lid of the lunchbox. This taps into parental concerns over healthy eating, alongside uncertainty over what is healthy to include in packed lunches. MY Example 3: CY CMY Mini Peperami Lunchbox Minis K Mini Peperami 0 4 21 30 NPM ratings: “In order to market children’s foods to parents, companies use health, emotion and the insight that families have changed, that parents are now cash rich and time poor. Guilt is a huge issue for parents.” Laura McDermott, Research Officer, Institute for Social Marketing, University of Stirling. Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Nutrition claim: ‘30% less fat.’ Quality claim: ‘100% pork salami.’ Image: The words ‘Lunchbox Minis’ are transformed into an image of a lunchbox by arranging the letters to fill a rectangular shape, and with the addition of a handle. Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: Energy kcal per 100g Mini Peperami Lunchbox Minis 375 kcal Saturated Fat per 100g 12.3g Sugar per 100g Trace Salt per 100g 3.5g There is a sixt h of a child’s daily recomm ende maximum suga d r intake in one Müller yo ghurt tub. Müller Crunch Corner Snack Size Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g 143 kcal 3g 17.8g* 0.2g *Applies to toffee flavour and approximates to chocolate.This analysis refers only to these specific flavours in the range. Image 1: Peperami Lunchbox Minis 22 23 Example 5: Example 6: Kellogg’s Coco Pops Cereal and Milk bars Fruit Bowl Fruit Flakes Raspberry with a yogurt coating Coco pops 0 4 25 Fruit Flakes 0 30 4 20 30 NPM rating: NPM rating: Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Summary of techniques used to market to parents: Nutrition claim: ‘Free from artificial colours,’ ‘free from hydrogenated fats,’ ‘source of calcium iron and 6 vitamins.’ Nutrition claim: ‘Natural colours.’ Quality claim: ‘The best choice for your kids’ lunchbox treat,’ ‘Kellogg’s have packed your kids favourite cereal into a soft and chewy cereal bar with a delicious milky layer on the bottom, making it a real anytime treat.’ Health claim: ‘Good for energy’. Images: A picture of the product on the side of a lunchbox, in which healthy foods such as grapes and a sandwich made with wholemeal bread are visible. Quality claims: ‘Made with real fruit’, ‘contains real yogurt,’ ‘ideal for lunchboxes, cereal toppings and home baking.’ Emotional insight: Text taps into parents’ experience of conflict over food choices in the context of packed lunches ‘now you can give your kids a great tasting snack that you can be sure won’t come back from school in the lunchbox. “I don’t have the time to look at everything. Traffic lights would be so easy.” A parent. Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: Despite de scribing itse lf as a kid’s tr eat, Coco P ops Cereal and Milk bars u se adult guide line daily amounts in displaying nutritional content. 24 Kellogg’s Coco Pops Cereal and Milk bars Saturated Fat, Sugar and Salt content: Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g 423 kcal 11g 41g 0.6g Fruit Bowl Fruit Flakes Energy kcal per 100g Saturated Fat per 100g Sugar per 100g Salt per 100g 449 kcal 11.9g 58.8g Trace 25 Example 1: McDonald’s McDonald’s combines messages to parents on its website(s) with those conveyed in its television advert for children’s Happy Meals. This technique is designed to increase positive brand perception. As an article in Brand Republic confirms ‘Using TV and online combined delivers up to 50% increase in positive brand perception, as well as a significant increase in likelihood of purchase. Results show 50% of the ‘tech-savvy’ population regularly go online while they are watching TV, enabling instant online response to TV ads.’ (33) Other types of non-broadcast marketing: Web, schools and community Other non-broadcast marketing examples During our research, we looked at company websites, parenting sites, sites of commercial and non-commercial organisations working with schools, and fast food outlets and identified multiple, less direct ways of communicating with parents. While it was not possible to apply our Checklist to these settings as they do not market just one product, we identified the themes of nutrition, health, quality, and family across these media. This mirrors the trends we have already identified in packaging, print and television marketing. The majority of the products we looked at included a web address on the packaging. We also analysed print and television adverts that directed viewers to company websites. Some companies often have different websites for brands, product ranges, specific products and promotions. Recent reports have drawn attention to the increasing activity of companies in schools and community settings. HFSS brands are among those working with schools. A report by the Commercialism in Education Research Unit, At Sea in a Marketing Saturated World: Schoolhouse commercialism trends 2007-2008, referred to the Walkers Football Fund, in which branded kits are sent to schools and clubs; and Kellogg’s Breakfast Clubs, in which school children can choose from the cereals as part of healthy eating education.(32) McDonald’s has recently been enjoying a period of financial success, announcing eight quarters of consecutive growth in May 2008 (34) and in August 2008, the creation of 4,000 new jobs in the UK to service the extra two million customers visiting restaurants per month compared with the previous year.(35) Commentators note that this constitutes a turnaround following the threatened closure of 25 restaurants in 2006,(36) and attribute the recent renewal to a change in image for the brand.(37) McDonald’s have made some changes to their menu, including the introduction of some new items and changes to sourcing, including using organic milk. Across the McDonald’s menu, some items are HFSS and some are not. This is true of the children’s Happy Meal of which McDonald’s sells more than 2 million per week in the UK.(38) For instance, the cheeseburger has a score of 9 according to the NPM, whereas the Hamburger scores 1, making it non HFSS. McDonald’s state on their website that three quarters of the items on the Happy Meal menu are non HFSS, however it does not mention which items on the menu (HFSS or non-HFSS) are the most popular. The use of meat and eggs sourced from Britain and Ireland forms the central premise of the Happy Meals television advert. In the advert, a large number of children, of various ages, and adults are shown taking part in arable and vegetable farming activities together including planting vegetables and hammering in fence posts, watering flowers and sowing seeds. A voiceover says, “By working together with British and Irish farmers, we ensure that only whole cuts of British and Irish beef, top quality potatoes and farm assured, white chicken breast go into our Happy Meals.” Meanwhile the camera pans out to reveal that what the adults and children have been working on is a floral depiction of a chicken, a cow and a sack of potatoes. The voiceover concludes, “That’s what makes McDonald’s.” Then the catch phrase ‘I’m lovin’ it,’ is shown with its accompanying jingle and the company’s ‘golden arches’ logo, and the web address www.mcdonalds.co.uk/ourfood The same marketing techniques used in the advert are repeated on the section of the website that the advert refers to. Marketing techniques from our Checklist used here include: repetition and elaboration of claims about the quality and provenance of the food and pictures of raw ingredients and images relating to farming, as well as another chance to view the television advert. Visitors to this section of the website are referred to another McDonald’s website, www.makeupyourownmind.co.uk Commercial and non-commercial organisations’ websites contained details of how working with schools also includes the opportunity to communicate with parents. The following examples show how brands which include HFSS products communicate with parents via websites, educational resources and community activities. 26 McDonald’s make up your own mind website This site uses every technique on the Checklist . It includes extensive reassurances to parents, particularly in relation to the Happy Meal, and to the general public, on every aspect of the company’s activities, including nutritional quality, sourcing of food, fair trade products, and employment. Endorsement comes from other parents, who act as ‘quality scouts.’ As such, the site represents an extremely comprehensive example of how companies can use websites in order to develop a positive brand image. 27 Example 2: Phunky Foods Another example is the website ‘Phunky foods’ at www.phunkyfoods.com which describes itself as a ‘comprehensive programme to teach primary school children key healthy eating and physical activity messages through art, drama, music, play and hands on food experience.’ It provides teaching material (at a cost) to primary schools. Sponsors include Nestlé and Northern Foods, whose brands include Goodfellas pizzas and Fox’s Biscuits. The website forms an integral part of the programme. The website states that the companies had no involvement in designing the content of the teaching material and that the logos do not appear on any of the teaching material designed for direct use by the children. However, the logos do appear on the home page, and on pages in the dedicated ‘parents zone’ of the website, and on some of the downloadable resources including fact sheets for parents to print out. In this way, parents are subtly reminded of the brands in association with education. Conclusions The British Heart Foundation calls for the toughest restrictions to prohibit the marketing of HFSS food and drink to children either directly or through their parents. This report demonstrates that some members of the food industry have responded to existing restrictions by advertising HFSS food and drink intended for children directly to their parents. The persistent use of health claims and emotional insight in the marketing of HFSS food misleads parents and reduces their capacity to make healthy choices for their children. The Government’s vision of a society where parents are supported by the food industry to have the knowledge and confidence to ensure that children eat well is far from a reality; by marketing of HFSS children’s foods to parents, companies are acting in direct opposition to the realisation of this vision.(39) Summary of findings At a time when social concerns about children’s eating habits are higher than ever, action is urgently needed. We found clear evidence of HFSS children’s products being marketed to parents in television, print, packaging and some forms of non-broadcast marketing. Across all the media we examined, HFSS products were generally presented as nutritious, healthy and of sound quality. The use of images, promotions and endorsements was also found in all the media we examined. We also found emotional insight used in television, print and on packaging. In most cases, our examples of marketing used more than one of the techniques from our Checklist. The examples presented in this report have demonstrated that HFSS children’s food marketing is undoubtedly being targeted at parents, both overtly and, in the case of other non-broadcast marketing, more subtly. The report offers a snapshot rather than an exhaustive analysis of the children’s food market but it is clear that marketing to parents is happening across a range of media. “Companies may be developing parent-focused television advertisements in order to persuade Governments that marketing to parents is acceptable, so that the nature of the advert becomes important rather than the nature of the product being advertised. The meta-message is that parents approve the product.” Tim Lobstein, Director, Childhood Obesity Research Programme, International Association for the Study of Obesity. 28 29 Parents are being misled What needs to happen? It is clear from the examples presented in this report that parents are being misled about the nature of HFSS foods. This affects their ability to make healthy food choices for their families and, in turn, the diet and health of children. It is clear that the current regulation on junk food marketing does not go far enough in protecting children from unhealthy foods. Action is urgently needed to meet the twin aims of empowering parents to make genuinely healthy choices for their children and creating a consistent regulatory environment that offers appropriate safeguards for children. “Parents need to be given clear and accurate information about the food they provide for their children. Childhood obesity is increasing significantly and will increase the chances of your child developing diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease. Clear food labelling helps busy parents to make healthy food choices on behalf of their children.” Dr Mike Knapton, Associate Medical Director, Prevention and Care, British Heart Foundation. Children’s food manufacturers are using emotional insight to market their products to parents. One of the most commonly used insights we found referred to the familiar experience of struggling to get children to eat healthily. In this way, marketers are suggesting that their products can satisfy both parental concerns about nutrition and children’s desires. There is no reason to presume that children’s desires cannot be satisfied by healthier foods. Another important emotional insight used in the examples in this report plays on the notion of a ‘time poor’ society. While marketing directed towards parents still overwhelmingly targets mothers, the changes in the labour market may mean that mothers and fathers feel more reliant on fast or convenience foods. Food companies are exploiting wider social concerns about poor eating habits among children to make health associations for their products. Health, nutrition and quality claims were found in all the media examined. The most common nutrition claims included ‘free from artificial colours and flavours and ‘good source of calcium.’ Health claims included ‘good for teeth and bones’ and references to ‘energy’ and quality claims included ‘good,’ ‘goodness’ and ‘natural.’ While some of these statements may be factually correct, the important point is that they deliberately present a partial picture. For example, a product may indeed be free from artificial flavours but this does not mean it is healthy or would not be subject to regulation in line with the nutrient profiling model. A ban on all junk food advertising on television before 9pm would mean that parents could be confident that any products they see advertised before 9pm are suitable for a child’s healthy diet. This would also end the current anomaly which means that HFSS foods cannot be advertised during children’s programming but are still marketed during programmes where children form a significant part of the audience. Indeed, the most popular programmes viewed by under 16s are not currently covered by the restrictions.(41) The UK Government must legislate to make the regulatory framework consistent. There must be equally stringent measures across broadcast and non-broadcast marketing and an end to the loophole that allows the claims that are outlawed in television campaigns to still be made on product packaging. The BHF has outlined a proposal(42) on how a regulatory system of regulating non-broadcast food marketing to children could work. Any practice that aims to promote unhealthy food to children should be prohibited. A mandatory front of pack food labelling system will help parents to understand the nutritional values of the products they are purchasing. We recognise that there is a debate taking place in the UK and Europe about which food labelling system is the best. While the UK Government supports the traffic light labels developed by the Food Standards Agency, some food manufacturers and retailers favour Guideline Daily Amount labels. The British Heart Foundation believes that a combination of Multiple Traffic Light colour coding and Guidelines Daily Amounts would meet the needs of the whole population. This would allow for the at-a-glance colour interpretations that many people find most useful while allowing those who wish to make more detailed analysis of nutritional content to do so. These measures would ensure that parents are genuinely able to distinguish HFSS foods from healthier alternatives and that both parents and children are better able to take responsibility for their nutritional health. The industry itself concedes that current debates mean it is helpful to provide such a partial picture. Quoted in Food Manufacture magazine in August 2008, Unilever’s product development manager commented “where it’s going to move to in the next few years is not so much reducing the negatives as accentuating the positives”. Our Checklist against which the marketing examples in this report were measured made a distinction between direct nutrition, health and quality claims. This distinction reflects how claims may be viewed from a legal perspective; however, in the examples here, these claims were used interchangeably. Each of the claims were used to contribute to an overall picture of ‘health’ and vitality, often used alongside images that were indicative of ‘health.’ Healthy looking, active children and families were one of the most common types of subject matter in the images used. Using such images alongside quality claims can present a ‘healthy’ image without making a direct health claim. There are regulatory inconsistencies between different media, which allow the marketing of HFSS food to children directly to continue.(40) Claims that are outlawed in television campaigns are still being made on product packaging. In addition, controls on other areas, including schools, other community settings and on websites, are minimal. 30 31 How you can get involved The British Heart Foundation needs your help to end to the conditions which allow companies to use the techniques we have described in this report to mislead parents. Visit our website at bhf.org.uk/junkfood There you will find more information about our work and how you can get involved in our campaign to stop parents being misled. Please let us know Let us know how you feel that about the food industry misleading parents, and email us the specific examples that you come across. We will share this information with other concerned parents and use it to continue to make the case for change. Get your kids involved And your kids can get involved too. Our highly successful Food4Thought campaigns help children understand how important diet and exercise is to their health. As part of the latest campaign, they can log on to www.yoobot.co.uk to create a digital, mini version of themselves called a ’Yoobot’. It’s a fun - and educational - virtual game which teaches children that how they live and what they eat affects their health and body. They’ll be able to choose what they feed their Yoobot for breakfast, lunch and dinner, as well as the type and amount of exercise it gets. Use our ‘ready-reckoner’ card We have included our ‘ready-reckoner’ card in the back of this report which explains food labels and can help you make healthy choices for your family. Let us know how whether you find this useful. Further information about this research and how you can get involved in our campaign is available at bhf.org.uk/junkfood If you would like to know more please email policy@bhf.org.uk or call us on 020 7554 0000. References 1. NHS Information Centre (2006); Health Survey for England 2005 Latest Trends. NHS Information Centre. 22. Marketing (2008); From light touch to iron fist. Marketing, 30 July 2008. 2. McPherson, K. Parry, V. Butland, B. Jebb, S. Kopelman, P. Thomas, S. Mardell, J. Foresight (2007); Tackling Obesities: Future Choices - Project Report. Government Office for Science. 23. Lee, Jeremy (2008); Food advertising shifts focus from kids to parents. Marketing, 8 July 2008. 3. Whitaker, R.C. Wright, J.A. Pepe, M.S. et al (1997); Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. The New England Journal of Medicine; 337: 869–73. 4. The Strategy Unit (2008); Food Matters: Towards a Strategy for the 21st Century. The Cabinet Office. 5. Steven Allender, Viv Peto, Peter Scarborough, Asha Kaur and Mike Rayner (2008) Coronary heart disease statistics. British Heart Foundation: London. 6. National Statistics, 2000. 7. Nelson, M. Erens, B. Bates, B. Church, S. Boshier, T. (2007); Low income diet and nutrition survey. Food Standards Agency. 8. HM Government (2008); Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives: A Cross Government Strategy for England. HM Government. 9. Hastings, G. (2003); Does Food Promotion Influence Children? A Systematic Review of the Evidence. University of Strathclyde Centre for Social Marketing. 10. Ofcom (2006); Television Advertising of Food and Drink Products to Children: Options for new restrictions; Research annexes 9-11. Ofcom. 11. Which? (2008); Government must switch on to TV ad failings. http://www.which.co.uk/press/press_topics/campaign_news/food/ barb_571_156546.jsp Which? September 2008. 12. Which? (2008); ‘Food Fables - the second sitting: The truth behind how food companies target children.’ Which, July 2008. 13. HM Government (2008); Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives: A Cross Government Strategy for England. HM Government. 14. Ofcom (2007); Television Advertising of Food and Drink Products to Children: Final Statement. Ofcom. 15. Lee, Jeremy (2008); Food advertising shifts focus from kids to parents. Marketing, 8 July 2008. 16. Business Insights (2008); Ethical and Wellness Food and Drink for Kids: Key product trends and manufacturer strategies. Business Insights Ltd. 17. Pidd, Helen (2008); We are coming for your children. The Guardian, 31 July 2008. 18. Jones, S. & Fabrianesi, B. (2007); Gross for kids but good for parents: differing messages in advertisements for the same products. Public Health Nutrition 11(6), 588-595. 19. Clarke, R. (2008); Focus on: lunchbox. The Grocer, 26 July 2008. 20. Lee, Jeremy (2008); Food advertising shifts focus from kids to parents. Marketing, 8 July 2008. 21. Lee, Jeremy (2008); Food advertising shifts focus from kids to parents. Marketing, 8 July 2008. 32 24. Marketing (2008); From light touch to iron fist. Marketing, 30 July 2008. 25. The Grocer (2008); Focus on: breakfast. The Grocer, 16 August 2008. 26. Ofcom (2007); Television Advertising of Food and Drink Products to Children: Final Statement. Ofcom. 27. CAP: www.cap.org.uk/cap/ 28. CAP Codes: www.cap.org.uk/cap/codes/ 29. Which? (2008); Government must switch on to TV ad failings: http://www.which.co.uk/press/press_topics/campaign_news/food/ barb_571_156546.jsp Which? September 2008. 30. The Grocer, 26 July 2008. 31. Rees, G. A. Richards, C. J. Gregory, J. (2008); Food and nutrient intakes of primary school children: a comparison of school meals and packed lunches. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics: 21: 420-427. 32. Molnar, A. Boninger, F. Wilkinson, G. Fogarty, J. (2008); At Sea in a Marketing-Saturated World: The Eleventh Annual Report on Schoolhouse Commercialism Trends: 2007-2008. Commercialism in Education Research Unit. 33. Thinkbox and the Internet Advertising Bureau (2008); Combine TV and online to boost brand perception say trade bodies. Brand Republic, 10 June 2008. 34. Independent, 16 May, 2008. 35. Independent, 6 August 2008. 36. Foley, Stephen (2008); McDonald’s: We’re lovin’ it! Independent, 6 August 2008. 37. Bowers, Simon (2008); The man who rehabilitated Ronald Mcdonald. The Guardian, 16 May 2008. 38. Bowers, Simon(2008); The man who rehabilitated Ronald Mcdonald. The Guardian, 16 May 2008. 39. HM Government (2008); Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives: A Cross Government Strategy for England. HM Government. 40. British Heart Foundation & Children’s Food Campaign (2007); Protecting children from unhealthy food marketing: A British Heart Foundation and Children’s Food Campaign proposal for a statutory system to regulate non-broadcast food marketing to children. British Heart Foundation. 41. Which? (2008); ‘Food Fables - the second sitting: The truth behind how food companies target children.’ Which? July 2008. 42. British Heart Foundation & Children’s Food Campaign (2007); Protecting children from unhealthy food marketing: A British Heart Foundation and Children’s Food Campaign proposal for a statutory system to regulate non-broadcast food marketing to children. British Heart Foundation. 33 Appendix Put a traffic light on every food label with your Ready-Reckoner Card Checklist of techniques used to market HFSS children’s foods to parents Content type: Examples of content deemed to be targeted at parents: Nutrition claims: Direct claims relating to the presence or absence of specific nutrients or ingredients such as, ‘a good source of calcium’; ‘low fat’; ‘free from artificial colours or preservatives’. Health claims: Direct claims relating to the product’s capacity to boost health, happiness and/or development, for instance, ‘good for growing kids’; ‘for strong teeth and bones’. Quality claims: Broad claims relating to an overall sense of wellness and wellbeing for people and the environment including ‘wholesome’; ‘natural’; real’; ‘full of goodness’. Also includes claims relating to quality/provenance of the ingredients used such as, ‘made with the finest ingredients’. Images: Use of images that particularly appeal to parents by referring to childhood or family life, such as depictions representative of child development: toddling, walking, talking; good school ability; sportiness; sound emotional health, happiness, politeness, and enthusiasm. Promotion: Inclusion of a promotion or special offer likely to appeal to family groups, including visits to venues or shows. Emotional insight: Attempt to tap into hopes, fears and feelings commonly experienced amongst parents including stress due to busy schedules or fussy eaters; guilt for not spending enough time with children, or not having time to cook; anxiety over child safety or development including anxiety about childhood obesity; desire to make a child happy. For example the product might claim to ‘make meal times more harmonious’; or viewers might be encouraged to ‘show them you care.’ Endorsement: Endorsement by a charity, body, nutritionist or popular figure, for instance sports persons and celebrities. If foods don’t have a traffic light label, try using the card below to make healthier choices. For foods you eat in large amounts, like ready meals, look at the ‘amount per serving’ and use the guide to judge if they contain high levels of fat, saturates, sugar or salt. For snacks, and other foods you eat in smaller amounts, look at the ‘per 100g’ information and use the table to choose those that fall into the green or amber categories as much as possible. Check claims such a ‘light’ or ‘reduced fat’ with care. A bag of crisps that claims to contain 25% less fat than normal crisps may still contain a lot of fat. Look at the actual fat content on the back of the packet and see what percentage it is of your daily maximum recommended amount. For more information, please see our website bhf.org.uk/junkfood Our Checklist made a distinction between direct nutrition, health and quality claims. This distinction reflects how claims may be viewed from a legal perspective. 34 35 © British Heart Foundation 2008, registered charity in England and Wales (225971) and in Scotland (SC039426). G449 British Heart Foundation Greater London House 180 Hampstead Road London NW1 7AW Phone: 020 7554 0000 Fax: 020 7554 0100 Website: bhf.org.uk