THE CRIME SCENE OF THE MIND: PROHIBITION, ENJOYMENT

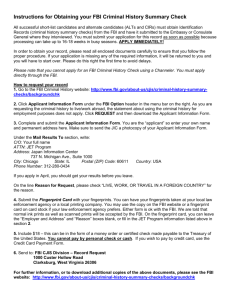

advertisement