AMooney - School of Media and Communication

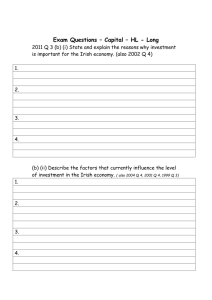

advertisement