BANKRUPTCY l Issue No. 1 l The hurdles of co

advertisement

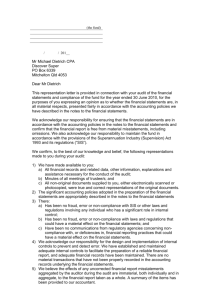

BANKRUPTCY l Issue No. 1 l The hurdles of co-owned property September 2014 Background Facts The Full Court of the Federal Court in Coshott v Prentice [2014] FCAFC 88 recently dealt with the issues of whether the purchase of co-owned property by a bankrupt was acquired beneficially or on trust for a family superannuation fund and, therefore, not divisible among creditors and, otherwise, whether the Court had power under the Bankruptcy Act to order the sale of co-owned property. Background facts Schlotzsky Nominee Company Pty Ltd (Schlotzsky) was the nominated trustee for the Superannuation Fund. Robert Coshott (who was to become bankrupt) and his wife, Ljiljana, were the directors of Schlotzsky. The contract for the purchase of the property identified the purchasers as Robert and Ljiljana Coshott but did not state whether they would take their interests as joint tenants or tenants in common. The appellants relied on a document entitled “Acknowledgment” which was signed by Robert and Ljiljana and provided that a one-half interest in the Property was purchased by Ljiljana and the other half interest was purchased in the name of Robert as trustee for the Coshott Family Superannuation Fund. The deposit to be paid on the exchange of the contracts was deposited in Schlotzsky’s business cheque account and a cheque corresponding to that amount of the deposit was drawn on the account a couple of days later. However, the solicitor for Robert and Ljiljana provided evidence that it was never suggested to him that the property was being purchased in trust for a Superannuation Fund. The solicitor stated that acting on instructions from Robert, he was directed that the words “joint tenants” should be typed on the transfer forms. Mullins Lawyers l eNews Publications l Page 1 At first instance The central question run at trial by the Coshott parties was whether Robert held his 50% interest in the property as trustee of the Superannuation Fund or, in the alternative, pursuant to a resulting trust in favour of Schlotzsky as trustee of the Superannuation Fund. In either case, under section 116(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act, Robert’s interest would not be property divisible amongst the creditors of the bankrupt estate. Conversely, if the Court found that Robert’s interest was held by him beneficially, then the property vested in the trustee in bankruptcy and was divisible amongst creditors. The Court at first instance held that any suggestion or arrangement tending to suggest that Robert purchased a 50% interest in the Property otherwise than beneficially “was and is a sham as that term has come to be used in the jurisprudence of this Court and the High Court”. Declarations were made to the effect that Robert acquired his interest beneficially, that the joint tenancy was severed by operation of section 58(1) of the Bankruptcy Act and that Robert’s interest vested in the trustee in bankruptcy. On appeal The appellants (Ljiljana and Schlotzsky) sought an alternative declaration that Robert’s interest in the Property was held on trust for the Superannuation Fund on the basis that it was purchased with fund monies. The appellants also challenged the primary Judge’s findings of a sham. The Full Court found that the sham doctorate was irrelevant in these circumstances. It held that the question was not whether the Acknowledgement formed part of a sham but rather what weight should be given to it as evidence of the existence of the resulting trust in respect of Robert’s interest in the property, as against all of the other evidence. The Full Court found that irrespective of the conclusion that the primary Judge mischaracterised the matters as a sham, the monies applied in the purchase of the property were not trust monies; hence, the primary Judge did not err in “reaching that conclusion and, therefore, in rejecting the basis on which the Coshott parties contended that the Property was held on a resulting trust for superannuation funds. The evidence as a whole against that conclusion was overwhelming”. Such evidence included the fact that the contract for the purchase of the Property was signed by Robert and Ljiljana without reference to any trust and that the solicitor acting for Robert and Ljiljana was instructed to arrange for the transfer of the Property to them as joint tenants. Secondly, there was no record that Schlotzsky as trustee of the Superannuation Fund held any interest in the property. Thirdly, there was no evidence of any activities by Schlotzsky as trustee of the Superannuation Fund. Fourthly, while it was true that the evidence established that funds for the deposit and purchase of the property were withdrawn from the account which was held by Schlotzsky as trustee for the Superannuation Fund, the primary Judge’s finding that the account in Schlotzsky’s name was in fact operated for Robert’s personal benefit was unchallenged. Accordingly, the Full Court found at [79]: “Robert’s conduct, therefore, both before and after the acknowledgment was purportedly made, was consistent only with him having taken his interest beneficially”. The Full Court found that the primary Judge correctly held that Robert’s interest was acquired by him beneficially and therefore vested in the trustee in bankruptcy. The appeal was subsequently dismissed save in so far as the primary Judge failed to appoint two trustees as required by s66G of the Conveyancing Act (NSW). The appellants also challenged the primary Judge’s orders for sale, alleging that the Court lacked power to order the sale of the property because neither s 30 of the Bankruptcy Act nor s 66G of the Conveyancing Act (NSW) conferred that power. The Full Court found (at [100]) that it must be the “case that the general power in s30(1) of the Bankruptcy Act does not extend to the making of orders for the sale of property which is coowned by a person who is not the bankrupt, thereby destroying their rights in that property”. The Full Court considered that the relief sought by the appellants would permanently extinguish Ljiljana’s rights in real property in order to facilitate the recovery of monies owed by the bankrupt, solely on the ground that she was a co-owner and that the sale would realise Robert’s interest. Section 66G is similar in effect to s38 of the Property Law Act (Qld). In relation to the s66G argument, the Full Court found that s79 of the Judiciary Act operates to capture and apply both procedural and substantive State law as a surrogate to federal law, thereby enabling courts exercising federal jurisdiction to provide remedies afforded otherwise only under State law. The Full Court remitted the matter back to the trial Judge to decide who should be appointed as trustees for sale. Mullins Lawyers l eNews Publications l Page 2 Mark Madsen Partner Mullins Lawyers t +61 7 3224 0241 mmadsen@mullinslaw.com.au Ruth Sainsbury Solicitor Mullins Lawyers t +61 7 3224 0382 rsainsbury@mullinslaw.com.au