China - lovehistory

advertisement

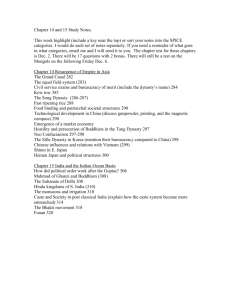

Page 1 China: Buddhist art: Many sculptures and paintings were made as aids for Buddhist meditation. The physical image became a base to support or encourage the presence of the divinity portrayed in the mind of the worshipper. Images were also commissioned for any number of reasons, including celebrating a birth, commemorating a death, and encouraging wealth, good health, or longevity. Buddhists believe that commissioning an image brings merit for the donor as well as to all conscious beings. Images in temples and in household shrines also remind lay people that they too can achieve enlightenment. XXXMandala: Mandala of Jnanadakini ,late 14th century Tibet (a Sakya monastery) Distemper on cloth; 33 1/4 x 28 7/8 in. (84.5 x 73.3 cm) Illuminated Manuscript: Illuminated pages from a dispersed Dharani manuscript, 14th–15th century Tibet (Zhalu monastery) XXXCloissone bowl: Dish with scalloped rim, Ming dynasty, early 15th century China Cloisonné; Diam. 6 in. (15.2 cm) XXXRed Plate: Seven-lobed platter with scene of children at play, Yuan dynasty (1279– 1368), 14th century China Carved red lacquer; Diam. 21 7/8 in. (55.6 cm) Gathering: Elegant Gathering in the Apricot Garden, Ming dynasty, ca. 1437 After Xie Huan (ca. 1370–ca. 1450) China Handscroll; ink and color on silk; 14 3/8 x 94 3/4 in. (36.7 x 240.7 cm) XXXBamboo wind: Bamboo in Wind, Ming dynasty, ca. 1460 Xia Chang (1388–1470) China Hanging scroll; ink on paper; 80 1/4 x 23 1/2 in. (203.8 x 59.7 cm) Inscribed by the artist (lower right): "Done by the Free and Easy Retired Scholar [Zizai jushi]; by Qian Bo (active mid-15th century; upper right), dated 1460; by Liu Jue (1410–1472; upper left), dated 1470 XXXWooded Mts. All and detail: Wooded Mountains at Dusk (detail), Qing dynasty (1644–1911), dated 1666 Kuncan (Chinese, 1612–1673) China Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper; 49 3/4 x 23 7/8 in. (126.2 x 60.6 cm) Inscribed by the artist Bequest of John M. Crawford Jr., 1988 (1989.363.129) High in the mountains, another traveler—perhaps a self-portrait of the artist—sits in meditation beneath a natural stone arch. One such rock bridge, located on Mount Tiantai, a site sacred to Buddhists, was said to provide access to paradise for anyone able to cross it. XXXLacquer box Page 2 Sutra box, Ming dynasty, Yongle period (1403–1424) China Red lacquer with qiangjin (incised and gilt decoration); 5 1/2 x 15 x 5 in. (14 x 40.6 x 12.7 cm) XXXShell and lacquer box: Incense container, Koryô dynasty (918–1392), 10th–12th century Korea Lacquer with mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell inlay (over pigment) and brass wires; H. 1 5/8 in. XXXWaterfall: Scholar by a Waterfall, Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), late 12th—early 13th century Ma Yuan (Chinese, active ca. 1190—1225) China Album leaf: ink and color on silk; 9 7/8 x 10 1/4 in. (25.1 x 26 cm) XXXTwinpines: Twin Pines, Level Distance, Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), ca. 1300 Zhao Mengfu (Chinese, 1254–1322) China Handscroll: ink on paper; 10 1/2 x 42 1/4 in. (26.7 x 107.3 cm) XXXSimple retreat: The Simple Retreat, Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), ca. 1370 Wang Meng (Chinese, ca. 1308–1385) China Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper; H. 53 1/2 in. (136 cm), W. 17 3/4 in. (45 cm) Signed: "The Yellow Crane Mountain Woodcutter Wang Meng painted this for the lofty scholar of the Simple Retreat" Politician: Garden of the Unsuccessful Politician, Ming dynasty, dated 1551 Wen Zhengming (1470–1559) China Album of eight paintings with facing pages of calligraphy; ink on paper; 10 7/16 x 10 3/4 in. (26.6 x 27.3 cm) Fishrocks: Fish and Rocks, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), dated 1699 Bada Shanren (Zhu Da) (Chinese, 1626–1705) China Hanging scroll; ink on paper; 53 x 23 7/8 in. (134.6 x 60.6 cm) Inscribed by the artist XXXMingcup: Stem Cup China, Ming dynasty, Xuande period (1426–1435) Porcelain painted in underglaze cobalt blue with anhua design; Diam. 6 5/8 in. (16.8 cm) XXXMingvase: Jar, Ming dynasty, Xuande mark and period (1426–1435) China Porcelain painted in underglaze blue; H. 19 in. (48.3 cm) XXXReliefmed: Medallion, Ming dynasty, late 16th–early 17th century China Ivory; Diam. 3 3/8 in. (8.6 cm) XXXFisherman: Fisherman, Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), ca. 1350 Wu Zhen (Chinese, 1280–1354) Page 3 Handscroll; ink on paper; 9 3/4 x 17 in. (24.8 x 43.2 cm) Inscribed by the artist XXXXHorse: Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), Horse and Groom in the Wind Old tree: Gu An, Zhang Shen and Ni Zan, Old Tree, Bamboo and Rock Hanging scroll. Ink on paper. Ht. 93.5cm. Yuan dynasty, c. 1369-73. National Palace Museum, Taipei. This specific bamboo painting was painted on paper, not using the traditional silk as a medium. Bamboo painting holds an important significance in Chinese painting. First of all, bamboo represents a true gentleman. It is plain, yet strong. Bamboo can hold strong through the rough winds. Secondly, painting bamboo takes great skill. It involves the most skilled form of Chinese art, calligraphy. Each leaf and section of the stem must be painted with the perfect stroke. Each stroke must be planned out so that the spacing of the stems and leaves and branches all go together. It is common in Chinese art that multiple artists will contribute to one piece. This painting is a perfect example of this. It shows honor and respect when an artist makes a contribution to an existing painting. This particular painting has three artists that have contributed. Gu An did the bamboo, Zhang Shen painted the old tree and calligrapher Yang Weizhan wrote the poem. The poem is about “painting bamboo while drunk” reffering to Gu An’s portion of the piece. Ni Zan later made a contribution that many critiques say spoils the composition of the piece. He painted the rock and added a long, messy inscription in the top left corner. This painting is from the Yuan dynasty. During this time period bamboo painting had a greater prominence than before. The painters were usually literari, gentlemen scholars who painted for enjoyment and self-improvement. During this time the variety of brushstrokes became important. Most of the paintings of this time are of the Buddhist influence. Poet: Huang Shen, The Poet Tao Yuanming Enjoys the Early Chrysanthemums Huang Shen’s (1687-c.1768) “The Poet Tao Yuanming Enjoys the Early Chrysanthemums” is a figure painting in ink on paper dating from the early Qing Dynasty. As the title suggests, it is a painting of the poet Tao Yuanming enjoying his favorite flower, the chrysanthemum, which is being tended by a young child. The 23 centimeter tall painting is in the style of most Song Dynasty figure paintings, in that it has no context, but displays only the important figures along with a short calligraphy by the artist explaining his work. It is thought that this figure style is a humourous twisting of the style of the famous Gu Kaizhi in the Tang Dynasty. Huang Shen was one of the “Eight Eccentrics” during the Qing Dynasty and this painting is an example of his unique Page 4 style. He playfully distorts the classical figure painting style with more tremulous brush strokes that outline and contour the figure more, like calligraphy. He mixes the refined with the vulgar by painting an acclaimed poet alongside a peasant boy in a sparse natural setting. The style is distinctly not classical, but popular as his paintings were done for wealthy businessmen and other patrons, not specifically for the royal court. XXXXWhiteporcelain: Guanyin. White porcelain. Fujian Dehua ware. Ht 22 cm. Early Qing Period, seventh century. Barlow Collection, University of Sussex. The Guanyin figure, from the Barlow Collection at the University of Sussex, represents the Buddhist goddess of Compassion. The figure is made of a fine white porcelain referred to as Dehua ware because it came from the Dehua site in the Fujian province located in southeastern China. The area did not become well known until the Ming dynasty and continued to grow into the Qing dynasty, when this particular Guanyin figure was made. The monochrome wares that were produced at Dehua are very difficult to date and do not have reign marks, making it hard to explore the history of the porcelain. The objects are identified by the quality of the porcelain, with its unique and very beautiful appearance, made of a soft white color and an elegant translucency. The porcelain represents a period of high achievement starting during the Ming dynasty, as it was widely traded throughout Europe because of its unique appeal and became known as blanc-de-Chine. Peachblossom: Peach Blossom Spring, Shitao [1642-1707], ink & color on paper The Peach Blossom Spring, now displayed in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C, is a Qing dynasty hand scroll done with ink and color on paper painted between 1705-07. The artist, Shitao, is considered to be one of the “Great Individualists” of the Qing dynasty whose style is greatly influenced by the Tang, Sung, and Yuan dynasties. This piece was completed after his transformation in 1697 from being a Buddhist monk to entering the commercial realm and being a full time professional artist at Yangzhou. Living a solitary life in the mountains, he became enthralled by nature and its relation to the artist’s use of line. He created a list of 13 texture patterns that all artists should learn and wrote the Huayulu, a document about the unity of man and nature and the yi hua, “one painting” or “one line.” The Peach Blossom Spring embodies these aesthetic philosophies. It has bold spontaneous lines, natural forms, diverse textures, multiple perspectives, and the characters are engulfed in the sublimity of their landscape and become mere details. The hand scroll depicts Tao Yuanming’s poem The Peach Blossom Spring, a dynastic narrative that tells the story of a lost fisherman from the Jing dynasty who comes across a Page 5 small, timeless, utopian community that had mysteriously fled to a mountain paradise during the Qin dynasty. Art historians suggest that Shitao painted topographical pieces, like this one, because of the politics of his own time concerning the instability of the Qing dynasty and his growing interest in dynastic history sparked by his newly found imperial identity (he is part of a princely lineage). The hand scroll has the classic elements of a topographic landscape—the cracked-ice pattern of the field, the solitary ploughman, the mist around the city gate, and the bird’s-eye-view. Breakingwaves: BREAKING WAVES AND AUTUMN WINDS early 16th century Dai Jin , (Chinese, Chinese, 1388-1462) Ming dynasty Ink on paper H: 29.9 W: 1112.9 cm China XXXdwelling: DWELLING IN SECLUSION IN THE SUMMER MOUNTAINS 1354 Wang Meng (ca. 1308 - 1385) , (Chinese, Yuan dynasty Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk H: 216.1 W: 55.2 cm China landscape: LANDSCAPE AFTER NI ZAN AND CALLIGRAPHY IN STANDARD SCRIPT ca. 1703-05 Bada Shanren (Zhu Da) , (Chinese, Chinese, 1626-1705) Qing dynasty Album leaf; ink on paper cm China bamboocreek: THE PURE RECLUSE OF BAMBOO CREEK 15th century Anonymous, traditionally attributed to Ni Zan (1306-1374) Ming dynasty Handscroll; ink on paper H: 55.4 W: 24.3 cm China Page 6 woman: STANDING FIGURE OF A WOMAN 16th century Tang Yin , (Chinese, Chinese, 1470-1523) Ming dynasty Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk H: 126.7 W: 69.7 cm China bamboogrove: STUDIO IN BAMBOO GROVE ca. 1490 Shen Zhou , (Chinese, 1427-1509) Ming dynasty Ink and color on paper H: 26.4 W: 368.1 cm Xiangcheng, China This short handscroll depicts a studio, which contains a small group of thatched and tiled huts surrounded by a bamboo grove on a small and flat island at a lake side. A scholar with a lute and a container of books sits in the hut in front of a calligraphy screen. There is a bridge behind the hut connecting the island with the mountain path. An open pavilion is located on the near shore across from the island. There is a group of tall trees in the left foreground hills, which gives a view from the studio. Spingstream: SEEKING A LINE OF POETRY BY A SPRING STREAM ca. 1500 Shen Zhou , (Chinese, 1427-1509) Ming dynasty Hanging scroll; ink and color on satin H: 162.0 W: 54.5 cm China cliff moon: REMINISCENCES OF NANJING : CLIFF-BORDERED MOON 1707 Shitao , (Chinese, 1642-1707) Qing dynasty Album; ink and color on paper cm Yangzhou, Jiangsu province, China orchids: ORCHIDS, BAMBOO, AND ROCK ca. 1700 Shitao , (Chinese, 1642-1707) Page 7 Qing dynasty Hanging scroll; ink on paper cm China Bodyguard: Portrait of the Imperial Bodyguard Zhanyinbao, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), dated 1760 Unidentified Artist (18th century) China Returninghome: Returning Home, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), ca. 1695 Shitao (Zhu Ruoji) (Chinese, 1642–1707) China Album of twelve paintings; ink and color on paper; Each painting leaf: 6 1/2 x 4 1/8 in. (16.5 x 10.5 cm); Each album leaf: 8 5/16 x 5 5/16 in. (21.1 x 13.5 cm); W. of double page: 10 5/8 in. (27 cm) Facing pages inscribed by the artist From the P. Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Family Collection Gift of Wen and Constance Fong, in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Douglas Dillon, 1976 (1976.280i) (Shitao was only two years old when the Ming dynasty fell. Saved by a loyal retainer, he was given sanctuary and anonymity in the Buddhist priesthood. In the late 1660s and 1670s, while living in seclusion in temples around Xuancheng, Anhui Province, he trained himself to paint. After many years of wandering from place to place in the south and spending nearly three years in Beijing, Shitao moved to the commercial center of Yangzhou around 1695, where he renounced his status as a Buddhist monk and supported himself through his painting. Drawing upon his love for natural scenery and his technical facility with brush and ink, Shitao created the most original landscape style of the seventeenth century. ) (A scion of the Ming imperial family from a branch enfeoffed in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, Zhu Da became a "crazy" Buddhist monk, shamming deafness and madness in order to escape persecution after the fall of the Ming dynasty. Lodging his feelings of frustration and vulnerability in his art, he created a deeply personal expressionist style that reflects his ambivalence about his life in hiding and his failure to acknowledge his identity as a Ming prince.) evening clouds: GaoKegongEveningCloudsOnAutumnMtsScrollFragment Artist: Gao Kegong Title: EVENING CLOUDS ON AUTUMN MTS SCROLL FRAGMENT Page 8 Chinese paintings: Materials: The artist used brush, ink, and color pigments on paper to create this handscroll. Ink, whether applied to silk or paper, cannot be altered once the brush touches the painting surface. By adjusting the amount of water mixed with the ink, and by handling the brush lightly, the artist can create a variety of tones, from light to dark. Calligraphy: The same tools (brush, ink, silk, and paper) are used for both writing and painting. Chinese is traditionally written in columns from top to bottom and right to left. There are strict rules about the order and execution of individual brushstrokes to form characters. But like the painter, the calligrapher is allowed the freedom to express his thoughts and feelings by the choice of calligraphic style he uses to write his characters, as seen in this handscroll. In China, calligraphy is considered a higher or purer form of artistic expression than painting. Both verbal and visual communication can be achieved with a single Chinese character. By looking at the character for mountain, which resembles one central peak surrounded by two smaller peaks, one can see the visual relationship of the characters to their meaning. Similarly, the flowing nature of water is suggested visually in the character for water. XXXNi Zan’s painting landscape: nizan 1 and 2 XXXXBird1 Anonymous Southern Song artist, Loquats and Mountain Bird Bird2 Anonymous (Song), Duckling Flowers1 Ma Lin, Layers on Layers of Icy Silk Flowers2 Qian Xuan (ca. 1235- after 1301), Autumn Melon Flowers3 Wang Qian (Yuan), Peony Plum Wu Zhen (1280-1354), Plum and Bamboo Treebamboorock XXXXWu Zhen (1280-1354), Old Tree, Bamboo and Rock Fuchun XXXXHuang Gongwang, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, some influence of the monumental style but not used to create the sense of monumentality in the landscape, more a musical device in his case; some Page 9 areas of complexity and other areas that are almost barren; a sense of "writing" the painting rather than painting it Dongqichang This Ming artist, Dong Qichang, almost always painted "pure landscapes" or landscapes without figures, without narrative interest, without some element of human interest. His paintings avoided naturalism because, he said, a painting cannot begin to equal the beauty of the real world. But on the other hand, the natural world could not equal what an artist could do with brush and ink. This painting is one which has several layers of meaning to it. In one sense, it appears to be like a map, a painting of a Buddhist monastery on a mountain. It also is a demonstration of the artist's skill with the brush and the particular principles of composition that he promoted in his own writings about theory. It is a painting which demonstrates his knowledge of "old" styles, of the monumental style, in particular. It is also close to abstract in the dynamism of the forms which create some visual turmoil. This may be the deepest message, a personal and political statement in which the artist takes an old and familiar type which had been associated with order and stability, and deliberately turns it into a painting of disorder and instability. To understand the lack of color in many Chinese landscape paintings, one must fully appreciate the interrelationship of calligraphy and painting. Calligraphy and painting use the same formats and tools (brush, ink, paper, and silk). The basic methods of handling a brush and ink to create the individual strokes of a Chinese character can also be used to create descriptive lines and textures in painting. It was during the Tang dynasty that the full expressive potential of ink was realized, as suggested in this quote from the ninth-century art historian, Zhang Yanyuan: Grasses and trees may display their glory without the use of reds and greens; clouds and snow may swirl and float aloft without the use of white color; mountains may show greenness without the use of blues and greens; and a Page 10 phoenix may look colorful without the use of the five colors. For this reason a painter may use ink alone and yet all five colors may seem present in his painting. In this hanging scroll, entitled Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu, by the artist Ni Zan (1306–1374), the correspondence between calligraphy and painting becomes apparent. It is a sparse, seemingly simple landscape devoid of human presence. Western paintings, like photographs, tend to present images of landscapes from a fixed point of view with a mathematically constructed illusion of recession, or perspective, which makes space appear to recede toward a single "vanishing point." Chinese landscape paintings use a moving perspective based on the notion of three distances (near, middle, and far) which allows the eye to move between various pictorial elements without being limited to one fixed, static point of view. Thus, the viewer is encouraged to ramble through the landscape image. Ni Zan, using abstract brushstrokes to suggest three-dimensional forms, exploits the tension between surface pattern and the illusion of recession to animate his composition. In this painting, where the bottom section acts as the foreground while the top acts as the background, a series of diagonal forms draws the viewer's focus upward across the picture surface as well as deeper into the represented space. At the bottom of this scroll, the foreground contains textural details of the side and top of the rocky shoreline, while the trees are presented from a level, or frontal, perspective. The water (the unpainted paper surface) and the less detailed, smaller-scale rocks and trees in the middle ground suggest receding space. The large mountain in the upper section of the scroll is shown as if the viewer were looking up at it. The smaller, pale hills to its right convey the massive size of this mountain and create a sense of deeper distance within the painting. Summer mts.: Summer Mountains Attributed to Qu Ding (active ca. 1023–ca. 1056) Handscroll; ink and light color on silk; 17 7/8 x 45 3/8 in. (45.3 x 115.2 cm) Summer Mountains, attributed to the mid-eleventh century artist Qu Ding, a court painter employed by Emperor Renzong (r. 1023–63), presents a vast, panoramic landscape of a summer evening following a rain shower. By juxtaposing immeasurably high mountains with minute details of human activities, the artist conveys the Daoist belief of the primary importance of nature, and of man's small yet harmonious existence within this orderly universe. The contrast of the dark, velvety ink washes and brushstrokes that define the mountains and trees with the empty, unpainted areas that suggest clouds, mists, and water is a visual reference to the rhythmic flow of the opposing forces of yin and yang (dark/light and wet/dry) found in nature. Page 11 The concept of traveling through time and space in one's imagination is exemplified in this painting. Beginning at the right, imagine unrolling this handscroll slowly toward the left about a foot or so at a time, identifying with the tiny human figures in the landscape so that you can walk along its pathways and relax in its pavilions and temples. In this way you focus on small sections in sequence, creating a visual journey through the dense wet foliage and mountain passes on this summer evening. Garden: Elegant Gathering in the Apricot Garden (detail), 1437 After Xie Huan Handscroll; ink and color on silk; 14 3/4 x 94 3/4 in. (37.5 x 240.7 cm) Painting, calligraphy, and poetry are referred to as "the three perfections" and are traditionally considered the highest forms of artistic and intellectual expression in China. By applying a brush filled with ink or color on either a silk or paper surface, the Chinese artist and calligrapher could paint or write in a variety of traditional formats, including handscrolls, hanging scrolls, albums, and fans. The artist's primary intention was not to reproduce or describe the outward appearance of his chosen subject, whether a landscape, a flower, a bird, or a human being, but to capture its inner nature or essential spirit. The brushstrokes of a painting were thought also to reflect the individual artist's state of mind. An inscription, dedication, and/or poem might be written directly on a painting by the artist or a close friend. Comments, called colophons, by later owners and admirers of a painting are often added on the mounting. These writings are viewed as a vital part of the work of art and add another level of understanding and appreciation for a specific work of art. In Elegant Gathering in the Apricot Garden, each participant at the party composed a colophon that was added to the completed handscroll, including a preface composed by Yang Shiqi (1365– 1444), the eldest guest in attendance, describing the circumstances of this festive event. The early Ming dynasty was a period of cultural restoration and expansion. The reestablishment of an indigenous Chinese ruling house led to the imposition of court-dictated styles in the arts. Painters recruited by the Ming court were instructed to return to didactic and realistic representation, in emulation of the styles of the earlier Southern Song (1127–1279) Imperial Painting Academy. Large-scale landscapes, flower-and-bird compositions, and figural narratives were particularly favored as images that would glorify the new dynasty and convey its benevolence, virtue, and majesty. In Ming painting, the traditions of both the Southern Song painting academy and the Yuan (1279– 1368) scholar-artist were developed further. While the Zhe (Zhejiang Province) school of painters carried on the descriptive, ink-wash style of the Southern Song with great technical virtuosity, the Wu (Suzhou) school explored the expressive calligraphic styles of Yuan scholar-painters emphasizing restraint and self-cultivation. In Ming scholar-painting, as in calligraphy, each form is built up of a recognized set of brushstrokes, yet the execution of these forms is, each time, a Page 12 unique personal performance. Valuing the presence of personality in a work over mere technical skill, the Ming scholar-painter aimed for mastery of performance rather than laborious craftsmanship. Early Ming decorative arts inherited the richly eclectic legacy of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, which included both regional Chinese traditions and foreign influences. For example, the fourteenthcentury development of blue-and-white ware and cloisonné enamelware arose, at least in part, in response to lively trade with the Islamic world, and many Ming examples continued to reflect strong West Asian influences. A special court-based Bureau of Design ensured that a uniform standard of decoration was established for imperial production in ceramics, textiles, metalwork, and lacquer. Mu-Chi (1210-1275) detail from "Mother Monkey and Child" Persimmons and tigers The Kokka describes the "Persimmons" (see reproduction) as having a "super-mundane atmosphere". Perhaps it is greatly revered because of the "passion congealed in a stupendous calm" that Waley describes. Certainly, it is typical of the points made about Zen painting. The depth is implied by such short distances it is rather an openness than depth! It is like looking straight up into the sky where there is no dimension. It is concerned with placement, with the "abstract dispositions" but every stroke delineates physical reality. The shapes are fruit bulks and the lines are stems. Their interaction is wonderful to watch. This is probably the most popular painting in the West of all those mentioned in this paper. Following are the remainder of the reproductions attributed to Mu Chi Muchiman Priest Chien-tzu playing with a shrimp" (#28, see reproduction) is painted from a point of view close to Liang Kai's and is the only authentic painting with the same subject matter. He is placed similarly to Pu-tai: about the same distance from the bottom of the picture, and the figure is cantilevered from the left edge by his pole, the inscription riding above. The mass stroke is used to wash in the robe. To get at the difference let us compare the bamboo pole with that in Hui-neng. Mu's is done with an even smooth stroke held at the beginning and the end to form a soft larger darkening at the joints, whereas Liang's breaks are accentuated by black hooked strokes. Mu's jolly little man is quite different form the noble personalities of Liang Kai's paintings. He is completely unselfconscious. He is modestly but happily occupied with catching shrimp. Page 13 Fanqi1 Fanqi2 Landscapes Painted for Yuweng, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), dated 1673 Fan Qi (Chinese, 1616–after 1694) China Among the more conservative masters working in Nanjing were Ye Xin (active ca. 1640–73) and Fan Qi (1616–after 1694), both of whom worked in an unusually precise and realistic style. Both specialized in small-scale gemlike paintings depicting the rural scenery around their native city. Sensitive and lyrical recorders of the familiar, these artists were also innovative experimenters with light, atmosphere, and color whose art reflects a creative response to Western influences recently introduced to China by the Jesuits. One Hundred Horses (detail), datable to 1728 Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining) (Italian, 1688–1766) China Chinese court painters soon mastered the rudiments of Western linear perspective and chiaroscuro modeling, creating a new, hybrid form of painting that combined Western-style realism with traditional brushwork. A key figure in establishing this new court aesthetic was the Italian Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766), who lived in China from 1716 until his death in 1766 and who adopted the Chinese name Lang Shining. A master of vividly naturalistic draftsmanship and large-scale compositions, Castiglione worked with Chinese assistants to create a synthesis of European methods and traditional Chinese media and formats. 1600s